Vignette

Dawn rose on training day (TD) six at the National Training Center (NTC). The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR), “Blackhorse” attacked the rotational training unit’s (RTU) flank. Dealer Company, 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was the brigade tactical group’s (BTG) exploitation force lagered near Four Corners. The original plan had Dealer passing through a breach in the RTU lines near the terrain known as the Iron Triangle and destroying the brigade combat team’s (BCT) main command post (CP). However, conditions were not set, and success was hanging in the balance. The main body was decisively engaged and hemorrhaging combat power. Waiting to be committed, Dealer received an unexpected order. The tank company, consisting of nine main battle tanks (MBT), zero infantry fighting vehicles (IFV), and one short range air defense (SHORAD) system, was to wheel south, move through Hidden Valley, assault into Razish, and establish an attack-by-fire position to turn the BCTs southern flank. The only infantry support allotted would be whatever remnants of the defenders with whom they could link-up with inside the city. Even with little coordination, the mission was successful. Dealer Company penetrated into Razish, destroyed the few defending anti-tank guided missiles teams (ATGM) the RTU managed to position in the city and contained the RTUs strong points in the city, successfully turning the RTU flank. During the rest of rotation 23-08.5, Dealer Company would attack Razish three more times, with varying levels of infantry support. Each time, the attack met success with minimal casualties.

The events encountered during Rotation 23-08.5 are not one-off events. Each NTC rotation, Blackhorse spends days fortifying the urban training area of Tiefort City. In addition to the typical mix of infantry strong points, minefields, and mazes of barbed wire, Blackhorse integrates both IFVs and MBTs into the city’s terrain. These vehicles are used to shape the foothold fight, enable transitions, and serve as mobile strongpoints to anchor Blackhorse counterattacks. The integration of armored vehicles provides options for the defenders and dilemmas to the attackers. Further, tanks lead Blackhorse’s reinforcing attacks into the city to prevent consolidation by the RTU.

Problem

The Armor force has an urban terrain problem. Simply put, the armor community is poorly prepared to conduct urban operations as a part of the combined arms team in large scale combat operations (LSCO). As the Army continues to prepare for LSCO, Armor branch continues to fall behind in our ability to plan and execute urban operations.

Using armor in urban terrain almost always generates consternation. The reluctance to commit armor into cities typically boils down to one central point - vehicles in urban terrain (even if armored) are vulnerable to anti-tank equipped infantry. However, this critique fails to consider the simple fact that any maneuver element in urban terrain is vulnerable. The density and complexity of urban terrain forces every type of formation to change its form of maneuver to defeat a determined enemy. Armor formations are not unique. Finally, this view fails to appropriately consider combined arms integration, which will necessitate armor formations playing a supporting but key role.

Figure 1. Tankers of D Company, 1/11 ACR lead a counterattack into Razish. (U.S. Army photo by 11th ACR PAO)

At present, there are two primary doctrine publications that deal with urban operations, ATP 3-06, Urban Operations and ATP 3-06.11, Brigade Combat Team Urban Operations. The recent publication of ATP 3-06.11 at best does nothing to advance combined arms integration of the armor force, and in the worst case is a step backwards. As a case in point, chapters 3 and 4 discuss combined arms integration for offensive and defensive operations. Chapter 3 on offense dedicates a mere two pages to discuss employment roles and consideration of armored vehicles (defined as Strykers, Bradleys, and Abrams – a problematic grouping in itself) within the offense. In chapter 4 on defense, there is a single paragraph that discusses the integration of armor into strong points.2 The brevity concerning armored integration seems appropriate given that ATP 3-06.11 focuses on BCTs, until we consider that chapter 4 dedicates over three pages to emplacement of crew weapon systems entirely focused on dismounted antiarmor and machine gun teams. This fine level of detail in ATP 3-06.11 gets deep into the weeds prescribing Soldiers “wet down muzzle blast area[s]” and provides a detailed description of antiarmor backblast and explosive pressure.3 The combined arms mindset is further hindered with the inclusion of an entire paragraph dedicated to the doctrine of “Put Dismounted Infantry in the Lead”.4 This isn’t speaking to the generalized idea that infantry organizations ought to take the lead in planning and executing urban operations (which does have its own benefits), but rather it is the dogma that infantry must be in the lead with vehicles in trail.

ATP 3-06 takes a much broader approach to combined arms asserting that “In various stages of battle, as the preponderance of threats shift between infantry/anti-armor and IED/enemy armor, units may shift the lead elements between U.S. force infantry or armor”.5 This is certainly the correct view of how to best integrate armor and infantry formations and given the level of specificity afforded to other topics in ATP 3-06.11 is the better way in which to view the inclusion of armor assets in the urban fight.

Ironically, until recently, doctrine provided a more cohesive and effective reference for integrating mounted and dismounted maneuver in urban terrain. The Army Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (ATTP) publication series contained ATTP 3-06.11, Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain. This publication offered specifics on techniques for integrating armor with infantry, as well as providing analysis on the advantages and disadvantages of each technique noticeably absent from ATP 3-06 and ATP 3-06.11. These techniques provided an effective framework for leaders at the company and below level to combine arms, mitigate the relative vulnerabilities of elements of the combined arms team, and enhance the team’s overall effectiveness. The departure of this knowledge from doctrine, without an immediate replacement, prevents the Armored force and Armor branch from establishing a foundation of understanding and building experts in mounted warfare.6

To effectively prepare for the future, Armor branch must prepare for urban combat in four ways. First, Armor branch must promulgate doctrine that supports combined arms integration. Second, we must deliberately instruct Armor branch leaders on mounted urban planning and operations. Third, our training progressions must include vehicular and dismount integration. Finally, we need to shift our thinking of tank units as standalone tools and recognize that we will use armor to support infantry and engineers in urban terrain.

Precedent

The necessity to train tankers for urban operations is not new. As Kendall Gott wrote in the preface of Breaking the Mold: Tanks in Cities in 2006, “I witnessed firsthand the US Army’s doctrine and attitude for using armor in the city – it just wasn’t to be done.”7 Yet, in every war from World War II to the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, tanks are being employed in cities. Lessons being learned from the ongoing conflicts will shape combined arms actions, but to illustrate the importance we will focus on conflicts which have already been well studied and documented.

In the Second Battle of Fallujah in 2004, armor-infantry teaming was critical to the success of the battle. Throughout November 10,000 Americans and 2,000 allied Iraqi forces fought approximately 3,000 insurgents in prepared defenses.8 The Coalition plan was for armored spearheads to penetrate deep into the center of the city, with infantry moving to secure bypassed buildings and routes.9

As the assault of the city unfolded, armored vehicles acted both as the spearhead and as mobile, protected, firepower available to be called up from the rear. Lead vehicles provided cover to dismounted infantry and immediate firepower, while vehicles farther back would respond to destroy strongpoints as they were identified by dismounted elements.10 Army Abrams and Bradleys operating in sections with dismount support mitigated traditional weaknesses of tanks in cities. The vehicles didn’t blindly move into kill zones but had mutual support, and their firepower quickly suppressed and unhinged enemy lines. Meanwhile, the Marines, with fewer tanks, successfully demonstrated their role as assault guns. Marine Infantry would locate enemy strong points, then call the tanks forward.11

Looking further back from Fallujah, armor has consistently been used in urban terrain to mass firepower, defeat obstacles, and support infantry maneuver. The Battle for Hue City was one of a series of battles fought during the 1968 North Vietnamese Tet Offensive and highlighted both the advantages and limitations of armor in urban terrain. The signature feature of Hue is the city’s thick stone walls which encircle the city center and the city moat which is tied into the Perfume River. During the Battle for Hue City, Marine Corps M48 Patton tanks and M50 Ontos self-propelled guns supported Marine Infantry in two slightly different ways. First, the M48s provided exceptional firepower and protection, allowing the Marines to follow behind the heavily armored tanks and rapidly reduce strong points. Second, the M50s provided comparable firepower but traded protection for mobility.12

The main limitation of armor in urban terrain is the problem of mobility. On the first day of the battle, Marine tankers in M48s found themselves unable to cross a final bridge into the city due to the bridge’s weight classification. While the tanks would eventually cross into the city, at this early stage in the fight the tankers were only able to provide supporting fires to Marine Infantrymen who crossed the bridge and established a foothold on the far side. As the Marines pressed forward, they did so without armor support.13

Figure 2. Example of detailed techniques in previous editions of doctrine that can be reintroduced, ATP 3-06.11, 2011. (U.S. Army Graphic)

As the battle progressed, Marine armor successfully made it into the city and was used in a variety of ways to enable the maneuver of the Marine infantry units. By the second week of fighting, Marines in the city began to fully recognize the potential of using the M48s and M50s in concert to reduce enemy strongpoints. An M48 would move out in front of the infantry with an M50 close behind. As the M48 drew fire infantry on the ground would relay the targets to the M50 crew which would then use its superior mobility to move in front of the tanks, reduce the enemy position, or create breaches in walls.14 The use of the M48 and M50 in concert also highlights the reality that not all armor is created equal. An especially salient point as we consider the inclusion of the M10 Booker alongside the M1 Abrams and M2 Bradley.

Proposed Solutions

To educate leaders on urban operations, Armor branch needs to renew its focus on urban operations planning in all of Armor branch’s programs of instruction. Cities are vital hubs of political power, commerce, and popular will, which means Armies will be forced to fight in cities whether they intend to or not. Put simply, we need to plan for combat in cities.

The first change is to commit to lead our doctrine on combined arms urban operations. As the Army continues to expand on urban doctrine, it should provide greater detail on techniques and procedures to integrate armored vehicles into the urban environment. Doctrine gives commanders and staffs robust, adaptable principles which can be understood and refined. As ATP 3-06.11 and ATP 3-06 describe infantry and engineer best practices, future publications should give Soldiers best practices for vehicle integration.

Figure 3. M2 Bradley overwatches a street while infantry clear adjacent buildings during the seizure of the training village of Unen, National Training Center. (Photo by Christopher Jordan)

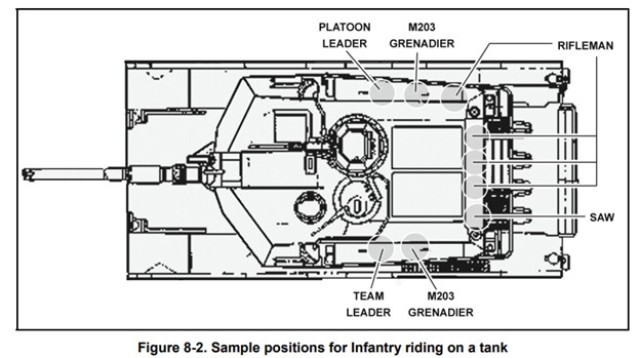

As urban doctrine is refined from the BCT level to the battalions and below, it should provide tools to plan and execute operations by not shying away from detail. Items to be added need to include specific capabilities and limitations of main gun rounds, machine gun employment, vehicle dead space, dismounts maneuvering with or on vehicles, and tank infantry phone (TIP) use. In particular, the on-going development of armor specific Training Circulars (TCs), specifically TC 3-20.31 Training and Qualification, Crew, can then provide tables and training scenarios not dissimilar to tools like Appendix H in TC 3-20.40 Rifle Marksmanship provides dismounted commanders with specific urban engagements to include in a training plan. At end state, doctrine should be refined, giving the tools and resources for any staff, regardless of background, to integrate armored vehicles into their operations. Its specifics and items must encompass the M1 Abrams, M2 Bradley, and M10 Booker platforms as distinct platforms with special emphasis on how differences between the M1 Abrams and M10 Booker in particular will affect their employment.

The development of focused combined arms urban operation planning in doctrine will enable urban operations to be included as a discrete block of instruction added to Armor courses. At a minimum, courses which produce platoon level and higher leaders or planners (i.e. Armor Basic Officer Leader Course, Cavalry Leader Course) need an urban module. The urban module should culminate in a planning exercise, a tactical decision exercise (TDE), or a simulated mission such as a tactical exercise without troops (TEWT). These urban modules should incorporate the lessons learned from two decades of counter insurgency operations (COIN) with the realities expected in a LSCO fight. By integrating urban planning into these courses, we establish early and often that cities aren’t something that can be “hand-waved” or wished away to other members of the combined arms team.

An urban module would have another, ancillary benefit. The urban module would reinforce the fundamentals of combined-arms operations and the complementary nature of the combined arms team. This would enhance the understanding of combined arms doctrine through practice rather than simply listing the advantages and disadvantages each formation brings to the fight. By including an urban block, we would inculcate an appreciation for branch integration and lessen the effect of branch parochialism.

Increasing the Armor force’s exposure to urban operations through professional military education (PME) naturally allows for the expansion and inclusion of urban operations training as a part of unit training cycles. Exposure in PME should further be reinforced by adapting the existing section gunnery tables to include section certification of a vehicle and squad, not just two vehicles. Given the time constraints in unit training cycles, the logical solution is to re-define section certification as either two vehicles, or a vehicle and a squad.

Again, given the limitation of time not all combined arms battalions need to place the same emphasis on urban operations. A CAB(A) designated as the Brigade breach element might have less focus on the urban fight, due to their mission alignment and modified table of organization and equipment (MTOE). However, the CAB(I) is a natural place where urban operations should be included early and often during a training progression. Situational Training Exercises (STX) that incorporate mounted-dismounted teaming in built up areas would build combined-arms teams from the ground up. The time a CAB(A) spends training the combined arms breach is time a CAB(I) can spend training combined arms urban operations.

For CAB(I)s or other units that expect to operate in complex terrain, integration should start at the team and squad level. As dismounts train to enter and clear rooms or operate within an urban training area, the mounted force needs to plan to support the dismounted force. Simply tasking the vehicles to “maintain an outer cordon” does not develop leaders for the complexity inherent to urban operations. On the mounted side of the equation, sections and platoons should train and rehearse operating in the built-up areas, directly communicating with and supporting dismounted operations, and vice versa.

Mounted dismounted integration should progress concurrent with an organization’s training progression. As the unit builds through platoon and company operations, these echelons should incorporate an urban component. At the platoon level, Task-organized platoons can train to attack and defend an urban area. As companies train, company teams attack and defend more complicated and dug-in urban terrain. TDEs and TEWTs are incorporated between training events to provide leaders additional exposure to different types of urban complexes. Ultimately, tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) are tested, refined, and perfected, and leaders gain familiarity working with others. Bottom line, if an armored brigade combat team (ABCT) plans to send the CAB(I) to clear complex terrain, the first time a tank commander/vehicle commander (TC/VC) encounters the realities of complex terrain should not be the streets of Razish, or the alleyways of a city down range.

Figure 4. A M2 Bradley section maneuver into an urban training to deploy dismounted infantry onto the objective. (Photo by CPT Joshua Johnstone)

The final major adaptation is cultural. The Army, and the expected battlefield on which we will fight are evolving. We must adjust with those changes. With the continued changes mandated by Army Structure (ARSTRUC), armor expertise is concentrating. Combined with the task organization changes resulting from the creation of the 19C military occupational specialty (MOS), there is a temptation to “double-down” and focus on large maneuvers in more open areas, while the rifle platoons focus on the urban problems. Deliberately inculcating a combined arms mentality will enable us to win. Armored fighting vehicles (AFV) have weaknesses. The war in Ukraine is full of examples of armored vehicles’ vulnerabilities. However, evolving technology in sensors and protection are mitigating traditional weaknesses of AFVs. Moreover, weakness does not equal obsolescence, nor does it mean there is no utility. Alone, dismounts lack protection and suppression and can be defeated by dug-in small arms. Alone, AFVs can be surrounded and overwhelmed. As part of a trained, combined-arms team, AFVs provide unique capabilities to ensure success. Even if armor has weaknesses, they still provide mobile, protected firepower capable of enabling dismounted infantry as well as providing responsive, lethal effects to enemy strongpoints. Armor is worst used in complex terrain (specifically urban terrain), when it is committed alone, manned by the untrained, and tasked ambiguously.

Conclusion

As the Army and the Armor force continually prepare for the next fight, the best time to incorporate the lessons of the past into preparation for the future is the present. The Armor branch has seen a variety of changes in the last decade from the inclusion of a tank company in the ABCT Cavalry Squadron to the recent adoption of the M10 Booker. An urban module in PME builds a baseline knowledge in the force. Updated and refined doctrine provides commanders and staff with the tools necessary to develop TTPs and create robust plans. A training progression that deliberately includes urban operations provides refinement, real-world lessons, and creates an expert force. As the Army continues to transition in contact, Armor Branch has an opportunity. We can revitalize our education, training, and culture on urban operations, enabling combined-arms teams that will fight on the battlefields of today and tomorrow. If we do these things, then we will enable our Soldiers to win, regardless of the location.

CPT Joshua Johnstone is currently assigned as the Major General James Wright Scholar, Raymond A. Mason School of Business at the College of William and Mary. His previous assignments include Commander, Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, commander, A Company, 1st Battalion, 68th Armor Regiment, 3rd ABCT, 4th ID, Battalion Maintenance Officer, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd ABCT, 4th ID, Company Executive Officer (XO), B Company, 2nd Brigade, 7th Infantry Regiment, 1st ABCT, 3rd ID, and Tank Platoon Leader, D Troop, 5th Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st ABCT, 3rd ID. CPT Johnstone’s military schools include the Cavalry Leader’s Course, Maneuver Captain’s Career Course, Army Reconnaissance Course (now the Scout Leader Course), Armor Basic Officer Leader Course and Airborne School. He has a bachelor’s of science in international history and foreign areas studies from the United States Military Academy.

CPT Christopher Jordan is currently assigned as an instructor, Cavalry Leaders Course, P Troop, 3rd Squadron, 16th Cavalry Regiment, 316th Cavalry Brigade. His previous assignments include Commander, Regimental Headquarters and Headquarters Troop (HHT), 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR), Commander D Company, 1st Squadron, 11th ACR, scout observer coach/trainer, Tarantula Team, Operations Group, NTC, Executive Officer (XO), C Company, 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT), 4th Infantry Division, and mortar platoon leader, Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd ABCT, 4th ID. His military schools include the Cavalry Leader’s course, Joint Firepower Course, Maneuver Captain’s Career Course, Infantry Mortar Leaders Course, Armor Reconnaissance Course, Armor Basic Officer Leader Course, and Airborne School. He has a bachelor’s of science in defense and strategic studies and Portuguese from the United States Military Academy.

Notes

1 Dr. Robert Cameron, “Armored Operations in Urban Environments: Anomaly or Natural Condition?,” ARMOR, May-June 2006, pp. 7-12.

2 Army Technique Publication (ATP) 3-06, Urban Operations, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 21 July 2022. Army Technique Publication (ATP) 3-06.11, Brigade Combat Team Urban Operations, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 27 July 2024, Paragraph 4-123.

3 ATP 3-06.11, Paragraph 4-62 and 4-63.

4 Ibid., 3-61

5 Ibid., 4-22.

6 Army Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (ATTP) 3-06.11, Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 10 June 2011.

7 Kendall D. Gott, “Breaking the Mold: Tanks in Cities,” Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, 2006, pg v.

8 Ibid., 95-98.

9 Ibid., 97.

10 Ibid., 99-101.

11 Ibid, 105-106.

12 John Spencer and Jayson Geroux, “Case Study #3 – Hue,” Modern War Institute at West Point, November 4, 2021. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/urban-warfare-project-case-study-3-battle-of-hue/.

13 Mark Bowden, Hue 1968, Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, 2017, 321.

Social Sharing