(This story appeared in the July-September edition of Army AL&T;Magazine.)

The importance of a contracting officer's representative (COR) in the current theater of operations cannot be overemphasized. In Afghanistan, CORs are on the front lines of ensuring that the performance of DOD contracts is sufficient and to standard. This necessary yet underappreciated position is often described as "the eyes and ears of the contracting officer" (KO).

However, the position of a COR downrange entails many additional responsibilities that are often overlooked when a commander nominates a COR or assigns the responsibility to a Soldier as an additional duty. The sheer volume of requirements produced daily to support the full spectrum of combat operations in Afghanistan keeps most KOs in U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Contracting Command tied to their desks 12 to 14 hours a day, leaving little time for contract administration and oversight.

KOs lean heavily on the CORs to ensure that the expectations of the U.S. government are being met. CORs face numerous challenges in fulfilling these responsibilities, but these challenges can be organized and overcome with proper training and an awareness of local contractors' expectations.

THREE LEVELS OF COR EXPERIENCE

Deployed CORs typically fall into one of three categories: experienced, inexperienced, or extra duty.

The experienced COR is often a government employee or service member whose primary duty for the deployment is contractual support and/or technical expertise in regard to a specific requirement. Generally, an experienced COR is well-equipped for the job and adjusts quickly downrange. However, there are very few experienced CORs in theater, and those who do exist are typically assigned to specialized DOD programs.

While it would be ideal for every KO to have an experienced COR, it is far more common for an inexperienced or extraduty COR to oversee a project. These CORs are assigned by their unit commanders for various reasons and come from all military occupational specialties and career fields. They tend to have limited or no COR or contracting experience, with any experience they do have coming from online courses taken before deploying or from a COR familiarization class at their pre-mobilization station.

While these programs have great value in indoctrinating a person to the philosophy and duties of a COR, they understandably do not prepare future CORs for many of the issues they will face downrange. Instead, the best preparation for a deploying COR would be to partner with a current or recent COR in theater. Together, they could identify areas of focus for dealing with Afghan contractors or KOs that may not otherwise have been considered.

Additionally, when CORs arrive in theater, they should shadow the COR they are replacing or one who works on a similar contract. Most military units are getting better at allowing their CORs time to work with their outgoing counterparts to learn about the contract and how to operate. Commanders must make this type of partnership a priority.

WORKING WITH AFGHAN FIRMS

Another challenge that downrange CORs face comes from the International Security Assistance Force’s counterinsurgency guidance that, to the greatest extent possible, KOs meet mission contracting needs through the Afghan First policy by contracting with Afghan-owned firms. The intent of the policy is to have a direct impact on the Afghan economy by employing

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

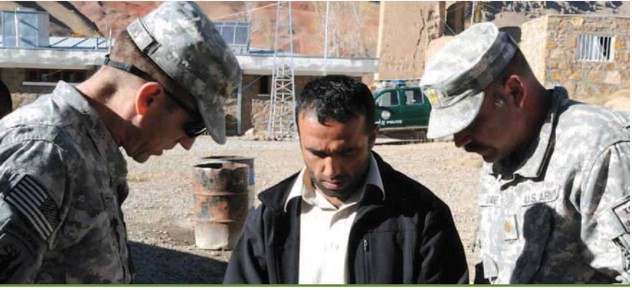

SFC Paul Carroll (left), Service Contracts Manager for the Directorate of Resource Management, 196th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade, South Dakota Army National Guard, and MSG Richard Albertson, a COR with the 196th, work with an Afghan contractor on forklift services and maintenance in Kabul, Afghanistan. (U.S. Army photo by CPT Anthony Deiss.)

Afghans and developing their businesses to be sustainable enterprises while meeting DOD contracting requirements.

This means that KOs contract with less experienced or new Afghan firms, of which there are many.

The program has been very effective in creating jobs and moving money into the Afghan economy. The idea is that the more Afghans who are employed, the less incentive there will be for the general population to look to the Taliban for monetary support.

The indirect result of the Afghan First policy on CORs is a fundamental and inadvertent increase in their responsibilities and sphere of influence. In addition to being the eyes and ears of the contracting officer, the COR becomes the face of the U.S. government to the Afghan contractor. KOs downrange simply have too much work to keep up with monitoring all of their contracts and seldom have the time to visit a project or job site.

Essentially, the COR becomes the only link between the contractor and the KO. Therefore, the COR must have a full understanding of the contract, act as an expert in cross-cultural business, understand regional enterprise practices, and exercise extreme patience in contract surveillance.

This is particularly true in construction contracts. Most solicitations given to Afghans for bidding are written in English. Most of the contractors have the expertise to complete the projects, but may not have the language skills to interpret the contracts.

It has become common practice for Afghan contractors to hire a third party business that understands DOD requirements to develop a proposal on their behalf.

A contractor may end up with a proposal that meets the technical criteria at the lowest price, but the Afghan employees do not understand the requirements beyond what they need to build. Traditionally, Afghan firms adhere to a different methodology and less stringent quality and safety standards than U.S. companies.

The COR is expected to enforce quality and safety standards outlined in the Statement of Work or Performance Work Statement, and to exercise patience in guiding the contractor to adhere to standards. However, the lack of construction experience of many of the inexperienced and extra-duty CORs presents a dilemma. To resolve this, the COR must partner with the KO to assess areas in which they are weak, such as knowledge of plumbing, electricity, or structural integrity. The COR and KO can then create a plan of action for the appropriate engineers, safety inspectors, or tradesmen to accompany the COR on an inspection.

A successful contract requires that a COR have this reachback through the KO to coordinate with the appropriate personnel. This not only contributes to the safety of all the Afghan employees on-site, but also ensures a good product while developing the Afghan firm’s knowledge and business capacity for future contracts.

THE CONTRACTOR'S PROBLEM SOLVER

In addition to becoming an expert in cross-cultural business, a COR also becomes the problem solver for the contractor. An Afghan contractor, unlike an American defense contractor, does not know how to navigate many of the potential issues when dealing with DOD.

For example, a COR may have to ensure that the Afghan contractor has proper access to project sites and is properly insured; that the contractor’s employees are treated well; that all pertinent issues are brought to the attention of the KO; and that the contractor is paid. The best way for a COR to deal with these types of problems is twofold: First, the COR must document all problems and solutions; second, the COR should actively engage and train the Afghan contractor when solving problems.

This requires a great deal of patience on the part of the COR; however, it allows the contractor to solve similar problems in the future.

Another COR responsibility is signing the DD Form 250, Material Inspection and Receiving Report, the document that accepts the products or services of the Afghan contractor on behalf of the U.S. government. A contractor cannot be paid unless the DD250 is signed, meaning that the COR is now also a source of payment, at least from the contractor’s perspective.

Afghans do not always understand the role of the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) and rely on the COR to ensure that they are paid properly and on time. Unfortunately, after the DD250 is signed and submitted to DFAS, it takes 30 to 45 days for the payment to reach the contractor’s bank. This presents a major issue to contractors, as they often do not pay their employees until they are paid themselves; as a result, they make repeated inquiries to the COR about when they can expect payment.

This again highlights the necessity of a partnership among the COR, contractor, and KO; together, they can help the Afghans plan for payments and allow the contractor’s business to run smoothly.

CHAIN- OF- COMMAND: ISSUES OF AUTHORITY

One of the biggest challenges that new or inexperienced CORs face downrange is balancing their authority as a COR appointed by a KO with the interests of their chain of command in a project or service.

All too often, there have been unauthorized commitments on contracts because ranking officers directed a contractor to do something that is not in the contract without the COR’s knowledge, or tried to supersede the COR’s authority. This is a particular issue with enlisted CORs on high-visibility contracts.

CORs therefore must "train" their chain of command in proper conduct when dealing with the contractors. Many highranking officers do not like the fact that the COR is authorized to interact with the contractor on contractual issues while they are not.

CORs must master the skill of respectfully ensuring that their authority is not confused with rank when dealing with people in their chain of command. To prevent confusion, leadership should attend the theater briefing that the COR receives from a Regional Contracting Center (RCC) before being appointed. Thus, the officers can learn about the RCC’s expectations and how to be involved in a contract without overstepping their roles.

Navigating the legalistic world of DOD contracts is difficult enough for CORs. However, when they become CORs in a contingency area of operation, they have a vital impact on the local economy, counterinsurgency operations, and regional relations. Though they probably hold one of the most underappreciated jobs in Afghanistan, CORs are also among the most important people for mission success.

A professional partnership of the COR, contractor, and KO will allow even the most inexperienced CORs to complete their missions successfully and become seasoned CORs by the time they return from deployment.

CPT MARK E. BALLANTYNE, a member of the Connecticut Army National Guard’s 1943rd Contingency Contracting Team, serves as a KO at the Bagram RCC under CENTCOM Contracting Command and as the RCC’s primary COR trainer. He holds a B.A. in marketing from Eastern University and an M.B.A. from Johns Hopkins University. Ballantyne is Level II certified in contracting.

Social Sharing