Between pilfering, mountain passes closed by snow, overturned trucks and attacks by hostile tribes, getting equipment and supplies to troops in Afghanistan is a challenge.

For a year, Army Lt. Col. Greg Younger, command transportation integration officer for the Surface Deployment and Distribution Command at Scott Air Force Base, lived in Pakistan and helped orchestrate and simplify the movement of military goods from Port Karachi in southern Pakistan through that country into Afghanistan through a mountain pass in the northwestern part of the country.

The Surface Deployment and Distribution Command is the newest command at Scott Air Force Base. It has a work force of more than 4,600 military and civilian employees worldwide and has contracts worth more than $1.8 billion annually with commercial surface moving companies that use trains, trucks, barges, pipelines and ships to move goods for the Department of Defense globally.

"Ten to 20 percent of the cost of a war is getting there," Younger said.

When Younger first arrived in Islamabad, Pakistan, it took an average of seven to nine days to get supplies and equipment through Pakistan's customs process. By the time he left a year later, the process was trimmed down to just more than a day.

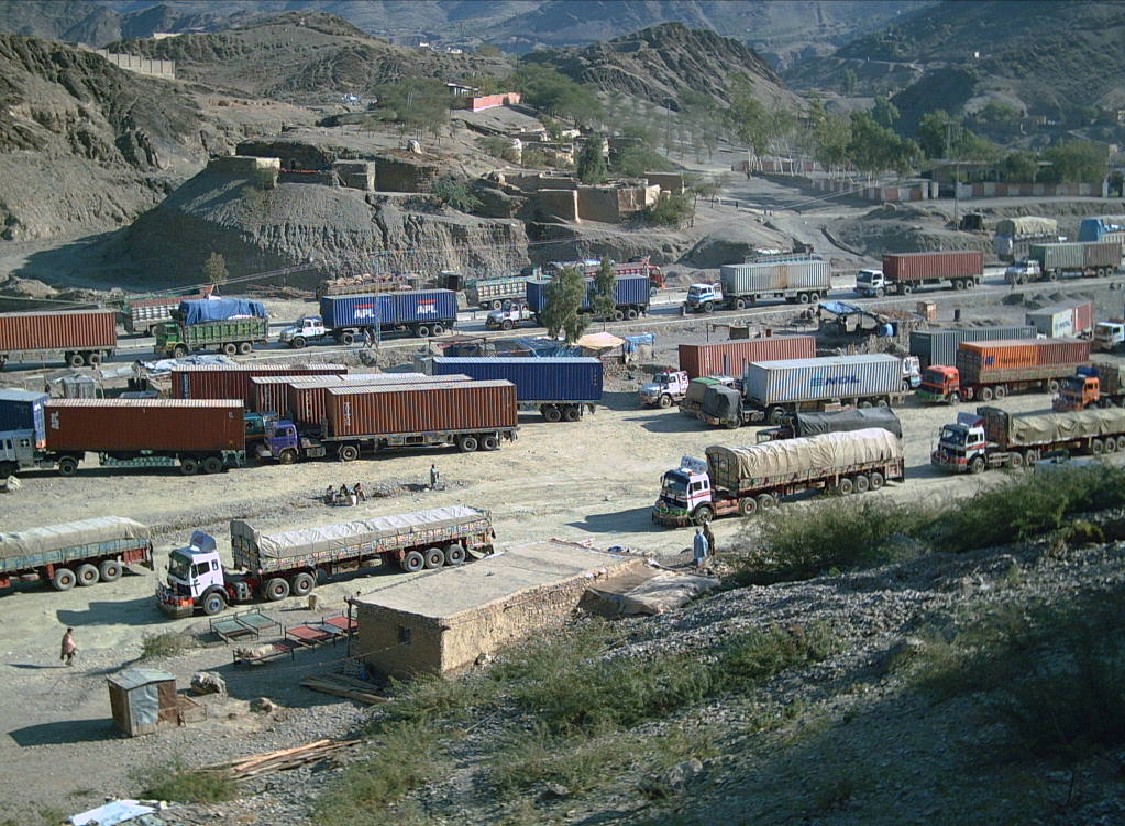

In one month, more than 3,000 containers carrying U.S. Department of Defense supplies are loaded onto contracted local trucks to make the 1,000-mile trek from Port Karachi into Afghanistan. Since he left Pakistan last year, the pace of containers into Afghanistan has increased to 4,500 a month.

The 1,000-mile trip takes seven to nine days from Port Karachi to Afghanistan. From Port Karachi to one of the four main U.S. bases in Afghanistan takes one truck between 17 and 21 days. Once the shipments reach the four main bases in Afghanistan, they are then distributed to the 125 base camps in the country.

Shipping supplies from the United States to Afghanistan takes between 45 and 49 days.

"They go through some pretty rough terrain and pretty rough areas," Younger said. "The most challenging part of the entire trip was that 45 miles after you leave Peshawar (Pakistan) into Afghanistan."

A majority of the pilfering and attacks on trucks carrying supplies for U.S. troops in Afghanistan happened while they sat for hours at the Afghanistan border waiting to get through customs at the Torkham Border Crossing. But attacks also occur when trucks travel through the FATA, or the Federally Administered Tribal Area, which is land and tribes in Pakistan that fall under no government law and is left largely alone by the Pakistani government.

"Pilfering is always a major issue in that part of the country and things do come up missing," Younger said. "The terrain is treacherous. Delivery trucks turn over in very narrow, mountainous passes."

During his year in Pakistan, 1.4 percent of containers were pilfered, resulting in the loss of approximately $72,000 worth of goods out of $7.2 million worth of shipped supplies. Sometimes the pilfered containers contained sandbags, other times, food and supplies, Younger said.

By streamlining and computerizing the customs process, Younger helped speed up the system to get the trucks past the border as quickly as possible. One of the things he did was hire Pakistani nationals to clear customs for the trucks before they reached the border.

"They know the terrain and they know the government," Younger said. "They know how things work and they have the relationships you need to make it work."

From narrow roads to unpredictable weather and attacks, the Khyber Pass through the mountains between Pakistan and Afghanistan presents a challenge to truck drivers.

In February 2008 the pass was closed for nine days due to heavy snow. Nothing was getting in or out of Afghanistan unless it was flown in. And usually, only sensitive shipments like weapons, ammunition and night-vision goggles are flown into the country, so they are not stolen.

Even though the deliveries were delayed, running out of needed supplies like food, water and ammunition was not a concern. The military keeps a 45 to 90 day supply of those items on hand in Afghanistan just in case, Younger added.

Everything needed by U.S. troops is brought into Afghanistan, from lumber for construction, to sandbags, food, water, equipment and clothing and personnel with the SDDC oversee and organize the transportation. The Department of Defense tells U.S. Transportation Command at Scott what it needs moved, U.S. Transportation Command figures out the best way to move the needed supplies and equipment and tasks Surface Deployment and Distribution Command or Air Mobility Command with the mission to get it moved.

And everything that moves is tracked at points along the 1,000- mile route.

At any given time, Younger or other SDDC personnel could check a database and find out where the truck or a specific container was.

"If a warfighter ever needed to know where his shipment was, I could tell him," Younger said. "We track it all pretty well. We try to get the warfighter and the equipment arrival synchronized. We want his equipment to be sitting there when he arrives."

When Pakistan opposition leader Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in December 2007, Younger suddenly found himself living in a country under martial law, all while still assuring U.S. troops in Afghanistan got the supplies they needed as quickly as possible.

"The assassination had a huge effect on the entire country. Within moments after martial law was imposed, the TV went out, the phones went out, the newspapers stopped printing," Younger said. "The whole country shut down."

U.S. military personnel working in Pakistan do not wear their military uniforms. They wear civilian clothing and try to blend in with the citizens there. Traveling 10 minutes outside of the capital city of Islamabad is like stepping back 1,000 years, Younger said.

"There is no electricity, no running water," he said. "There is no middle class in Pakistan. There are the educated and the well-to-do and there are the very, very poor."

Reprint permission granted by the Belleville News Democrat. Article originaly published on 4 November 2009 at <a href="http://www.bnd.com/404/story/993863.html">www.bnd.com</a>.

Social Sharing