FORT LEAVENWORTH, Kansas (Feb. 18, 2021) -- Since 1976, every U.S. president has declared February Black History Month, often inspiring celebrations and teachings honoring iconic African-Americans in history, like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman.

Fort Leavenworth has its own group of iconic African-Americans who have been recognized through streets and buildings named in their honor, as well as induction into the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame.

In 2015, historian Quentin Schillare included these historical figures in his book “Fort Leavenworth: The People Behind the Names.”

“In the 19th century, it was mostly general officers or famous folks (recognized as namesakes),” Schillare said. “Then, in the 70s and 80s … it occurred to the leadership of the Army and the leadership of Fort Leavenworth that they needed to broaden the base of the namesakes while they still had places to name.

“So, they went to NCOs and then diversity became important, … especially with the establishment of the Buffalo Soldier Monument.”

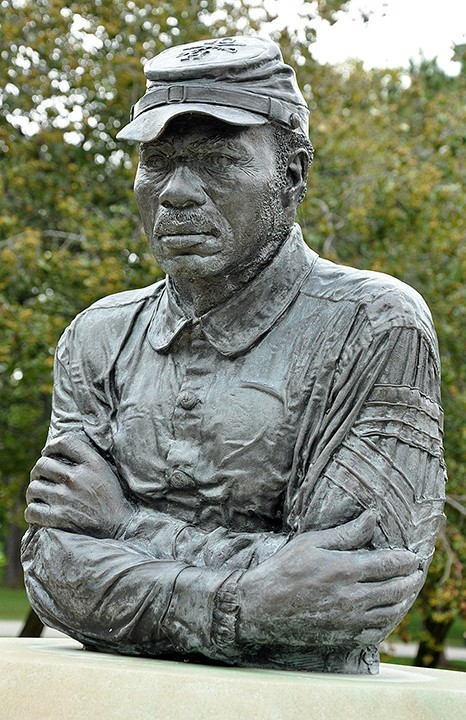

Buffalo Soldier Commemorative Area

The most obvious area on Fort Leavenworth dedicated to African-Americans is the Buffalo Soldier Monument, which was established on July 25, 1992, in honor of the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments.

The monument was later expanded into the Buffalo Soldier Commemorative Area in 1995 to include the Circle of Firsts and the Walkway of Units.

Gen. Roscoe Robinson Jr., the first African-American four-star general, was the first recognized with his bust dedicated on May 27, 1995.

Next was a monument honoring the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, also known as “Triple Nickles,” represented by a bust of 1st Sgt. Walter Morris, adjutant of the 555th, which was dedicated on Sept. 7, 2006. Triple Nickles was an all-black airborne unit of the U.S. Army that fought forest fires in the Pacific Northwest during World War II.

The third bust added was 2nd Lt. Henry Flipper, the first African-American graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., in 1877. His monument was dedicated on March 30, 2007.

The fourth bust in the Circle of Firsts is that of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Grierson, a white educator and advocate for Blacks after the Civil War, who organized and commanded the 10th Cavalry Regiment from 1866 to 1888. Grierson’s bust was dedicated on Aug. 8, 2012.

The fifth added was a bust of Gen. Colin Powell, who had many firsts, including being the first Black national security adviser, the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the first Black secretary of State. Powell is generally credited with the idea to honor the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Leavenworth. His bust was dedicated on Sept. 5, 2014.

The most recent entry honors the all-female 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. The battalion had several firsts, including being the first African-American Women’s Army Corps unit, the first African-American women as commissioned officers, and the first and only all African-American Army unit to deploy overseas during World War II. The monument, represented by a bust of Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the first African-American woman commissioned in the Army and the first and only commanding officer of the battalion, was dedicated on Nov. 30, 2018.

McNair Hall, the current home of The Research and Analysis Center, has the Buffalo Soldiers Conference Room, harkening back to the days when the building was a barracks for 10th Cavalry soldiers.

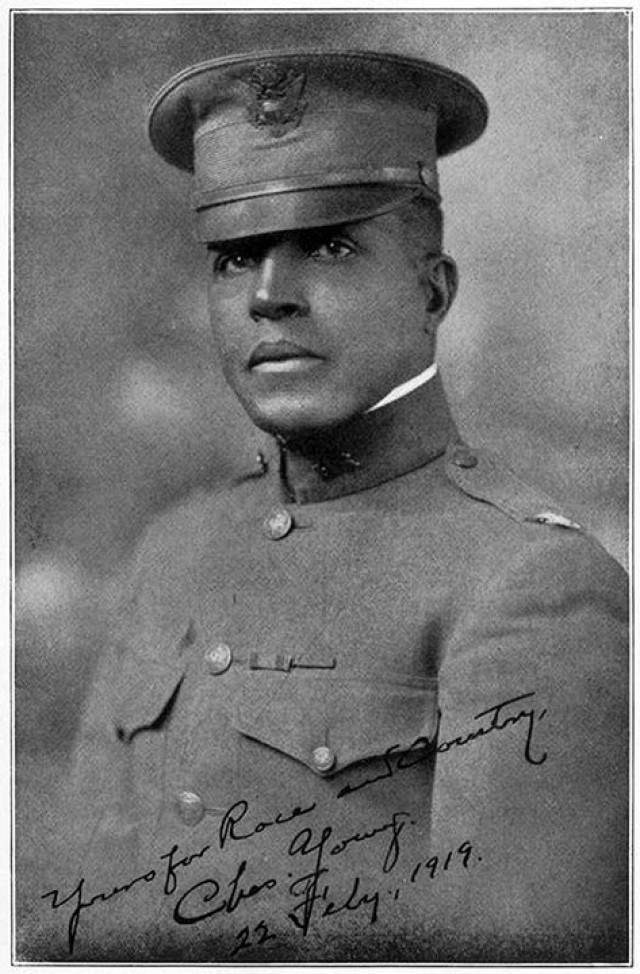

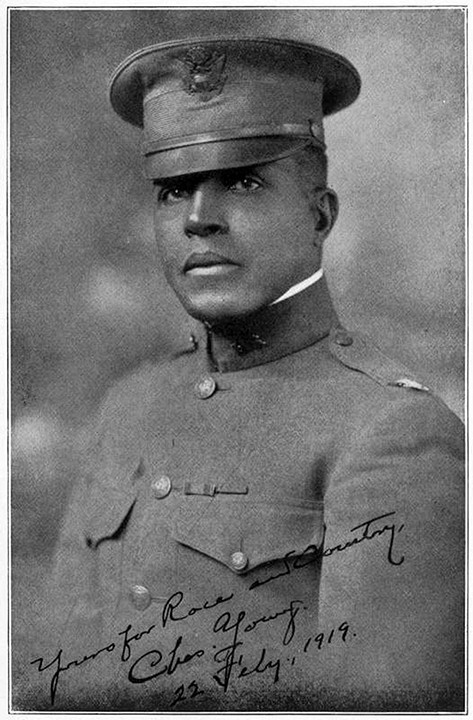

Col. Charles Young

The Young Conference Room, on the second floor of the Combined Arms Research Library, was named after Col. Charles Young and was dedicated on Nov. 9, 1994.

According to Schillare’s book, in 1889, Young became the third African-American graduate of West Point, and subsequently commissioned into the 10th Cavalry, eventually becoming the highest ranking African-American soldier in the Army during World War I.

Young died in 1922 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Pvt. Fitz Lee

Lee House, south of the Mission Command Training Program Headquarters, was built in 1911. Fitz Lee Hall (the Post Theater) was built in 1938 and dedicated in 1998. Both are named for Medal of Honor recipient Pvt. Fitz Lee.

“(Lee) is the only enlisted soldier that is the namesake for two places on post,” Schillare said.

According to Schillare’s book, Lee served at Fort Leavenworth with the 10th Cavalry from 1892 to 1894.

Lee earned the Medal of Honor for actions taken on June 30, 1898, when he rescued wounded men under fire in Tayabacoa, Cuba, with Troop M of the 10th Cavalry. He was medically discharged upon returning to Fort Leavenworth on July 5, 1899.

Lee died two months later on Sept. 14, 1899, and is buried in the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

Harry Hollowell

Hollowell Court and Hollowell Drive in the Pottawatomie Village Housing Areas were dedicated on June 19, 2009, and are named after Chief Warrant Officer 4 Harry Hollowell.

According to Schillare’s book, Hollowell enlisted in the 10th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Leavenworth in 1935, moving up several ranks in his first five years with the regiment before reassigning with the 10th Cavalry to Fort Riley, Kan. in December 1940. He later returned to Fort Leavenworth and commanded the 371st Army Band from 1960 to 1963. After he retired from the Army on Aug. 31, 1964, at Fort Hamilton, N.Y., he once again returned to Leavenworth and served as the director of music programs at the old U.S. Disciplinary Barracks until 1986.

Hollowell died in 2005 and is buried in the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame

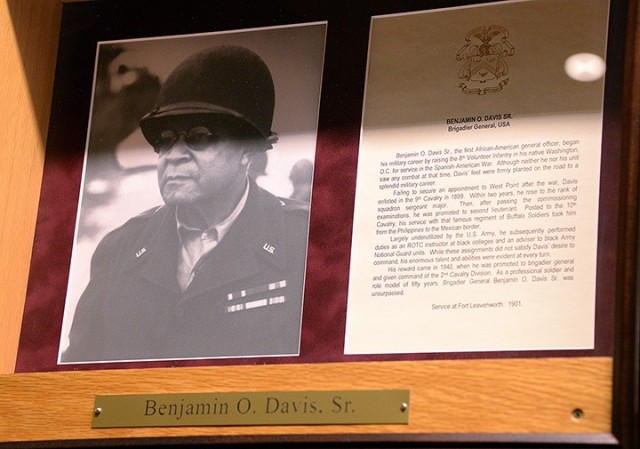

Two African-American soldiers have been recognized as members of the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame — Brig. Gen. Benjamin O. Davis and Sgt. Maj. William McBryar.

Davis, the first African-American officer to achieve general-officer rank, was inducted into the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame in 1993.

According to a Fort Leavenworth Lamp article written by Schillare, Davis, who was an enlisted squadron sergeant major in the 9th Cavalry at the time, only spent two weeks at Fort Leavenworth in January 1901 to take the officer candidate exam. He scored high enough on the exam to be commissioned as a second lieutenant on Feb. 2, 1901.

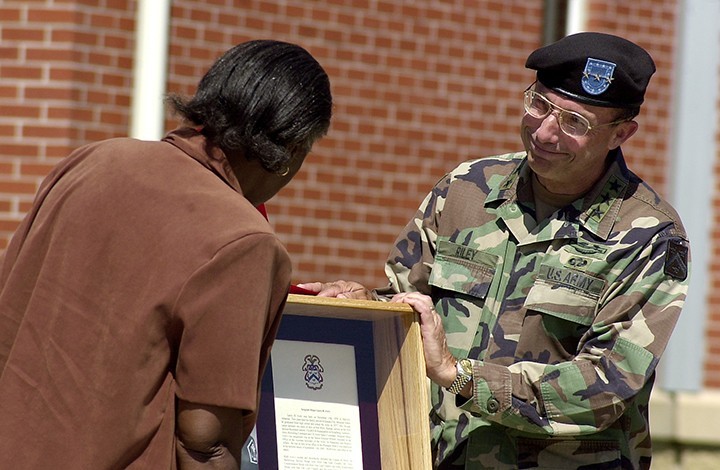

McBryar was inducted into the Fort Leavenworth Hall of Fame on May 17, 2009, in recognition of his long service as a noncommissioned officer following the Army’s declaration that 2009 would be known as the Year of the Noncommissioned Officer.

McBryar was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1890 “for his part in the capture of a group of Apaches who had retreated to a cave after a five-day, 200-mile pursuit. Under fire, McBryar maneuvered to a position where he could ricochet his bullets into the cave, forcing surrender.”

McBryar’s Medal of Honor was the first awarded to a 10th Cavalry soldier.

Single Soldier Quarters

On May 30, 2003, the Single Soldier Quarters was dedicated, and three of its five original wings were named after African-American soldiers — McBryar, Chaplain (Col.) Louis A. Carter and Sgt. Maj. Lacey B. Ivory.

According to Schillare’s book, Carter served 30 years in the Army with four Black regiments including the 9th and 10th Cavalries and the 24th and 25th Infantries. He served on the faculty of the Army Chaplains School at Fort Leavenworth in 1924. In 1936, he became the first African-American chaplain to attain the rank of colonel.

“Carter instilled in his men feelings of their worth as soldiers and pride in their black heritage,” Schillare wrote in his book.

According to Schillare’s book, Ivory grew up in Kansas City, Mo. Ivory, who served 24 years in the Army, was serving as the senior enlisted assistant to the assistant secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs when he was killed in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Legion of Merit.

Grant Gate

According to Schillare’s book, when Grant Gate was built in 1936, a large portion of it was constructed by African-American men of the Civilian Conservation Corps Work Camp 4717-C, which was on post from 1935-37.

“As you may guess, the ‘C’ stood for ‘colored,’” Schillare said. “So, the first thing people see when they enter post is an anonymous memorial to folks of African descent who contributed to the history of Fort Leavenworth.”

To download Schillare’s full book, visit https://usacac.army.mil/sites/default/files/ documents/cace/CSI/CSIPubs/FtL_PeopleBehindNames.pdf.

Social Sharing