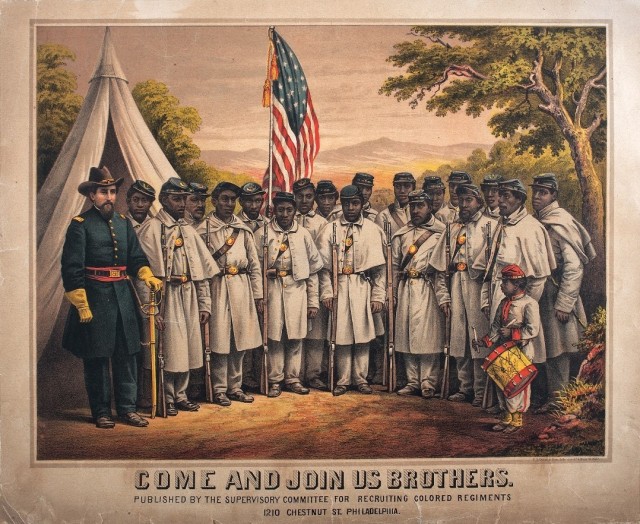

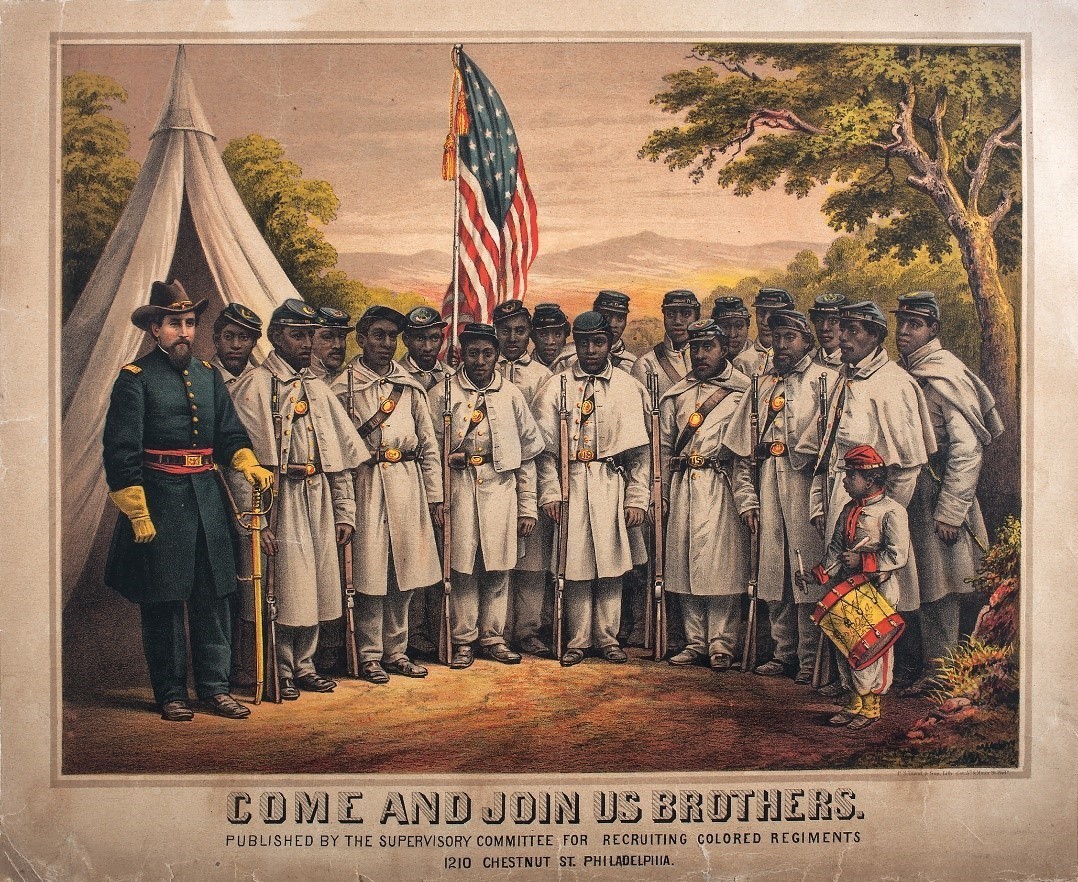

During the Civil War, the Union established and maintained regiments of black soldiers. This became possible in 1862 through passage of the Confiscation Act (freeing the slaves of rebellious slaveholders) and Militia Act (authorizing the president to use former slaves as soldiers). President Lincoln was initially reluctant to recruit black soldiers. This changed in January 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring freedom for all slaves in Confederate states.

The first black regiments to serve in the Civil War were volunteer units made up of free black men. These included the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers, 5th Massachusetts (Cavalry), 54th Massachusetts (Infantry), 55th Massachusetts (Infantry), 29th Connecticut (Infantry), 30th Connecticut (Infantry), and 31st Infantry Regiment. In May 1863, the War Department established the Bureau of Colored Troops for the purpose of recruiting African-American soldiers. These became the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and existing volunteer units were converted into USCT regiments.

New regiments were also formed from every Union state. While mostly made up of African-American soldiers, other minorities served in these regiments as well, including Native Americans and Asians, while white Union officers served as commanders. USCT regiments participated in all aspects of the Union war effort as infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers, though they were often used as rear action garrison troop

The first military action involving a black regiment was the Battle of Island Mound (Missouri), at which the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers were instrumental in ensuring a Union victory. USCT regiments also served heroically at the Battle of the Crater (Virginia), the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm (Virginia), the Battle of Fort Wagner (South Carolina), and the Battle of Nashville (Tennessee). They were also among soldiers at the fall of Richmond (Virginia) and were present when the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox.

By the end of the Civil War, there were 175 USCT regiments, containing 178,000 soldiers, approximately 10% of the Union Army. The mortality rate for these units was exceeding high. One of every five black soldiers in the conflict died, a 35% higher rate than other troops. In the process, sixteen USCT soldiers earned the Medal of Honor for their Civil War service.

After the war, Congress reorganized the U.S. Army into ten cavalry regiments and forty- five infantry regiments. These included two regiments of black cavalry (the 9th and 10th) formed at Fort Leavenworth, and four regiments of black infantry (the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st), formed at Jackson Barracks in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Fort Clark, Texas. When the Army pared back to twenty-five regiments of infantry in 1869, the four black infantry regiments were consolidated into two (the 24th and 25th).

These regiments, which came to be known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” were posted in the West and Southwest, mainly to quell disturbances between settlers and Native Americans. Though the origin of the name “Buffalo Soldiers” is in dispute, most sources agree that Native Americans (either Comanche, Apache, or Cheyenne) were the first to use the term to identify their black opponents. Eventually, the term was used to refer to all black soldiers.

The Buffalo Soldiers would serve in the United States military for the next fifty years, primarily in the Indian Wars of the 1890s, for which thirteen enlisted men and six officers received the Medal of Honor. The 9th Cavalry also replaced the 6th Cavalry in 1892 and served as peace-keepers for the Wyoming land dispute known as the Johnson County War. From 1892 to 1895, the commander of the 10th Cavalry was future World War I commander of American Expeditionary Forces and Army Chief of Staff Gen. John J. Pershing, whose service with the Buffalo Soldiers earned him the nickname “Black Jack” Pershing.

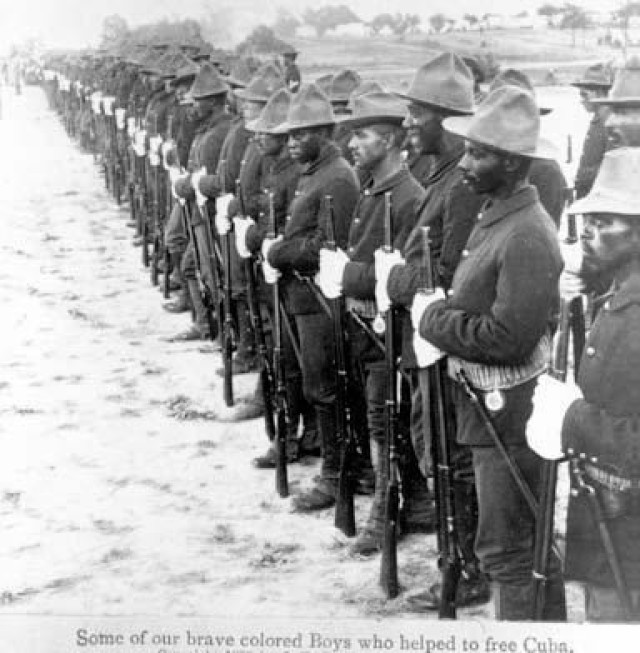

In January 1898, during a period of rising tension over Spanish atrocities in Cuba, the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor. Anti-Spanish sentiment rose following this incident, particularly in the “yellow press” newspapers of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, leading to a U.S. war declaration in April 1898. While the Navy was ready for this conflict, the Army had only 28,000 men in uniform. Enlistees, volunteers, and National Guard units soon added 220,000 soldiers, including 5,000 African- American men, but the only black troops who fought in the Spanish-American War were the Buffalo Soldiers.

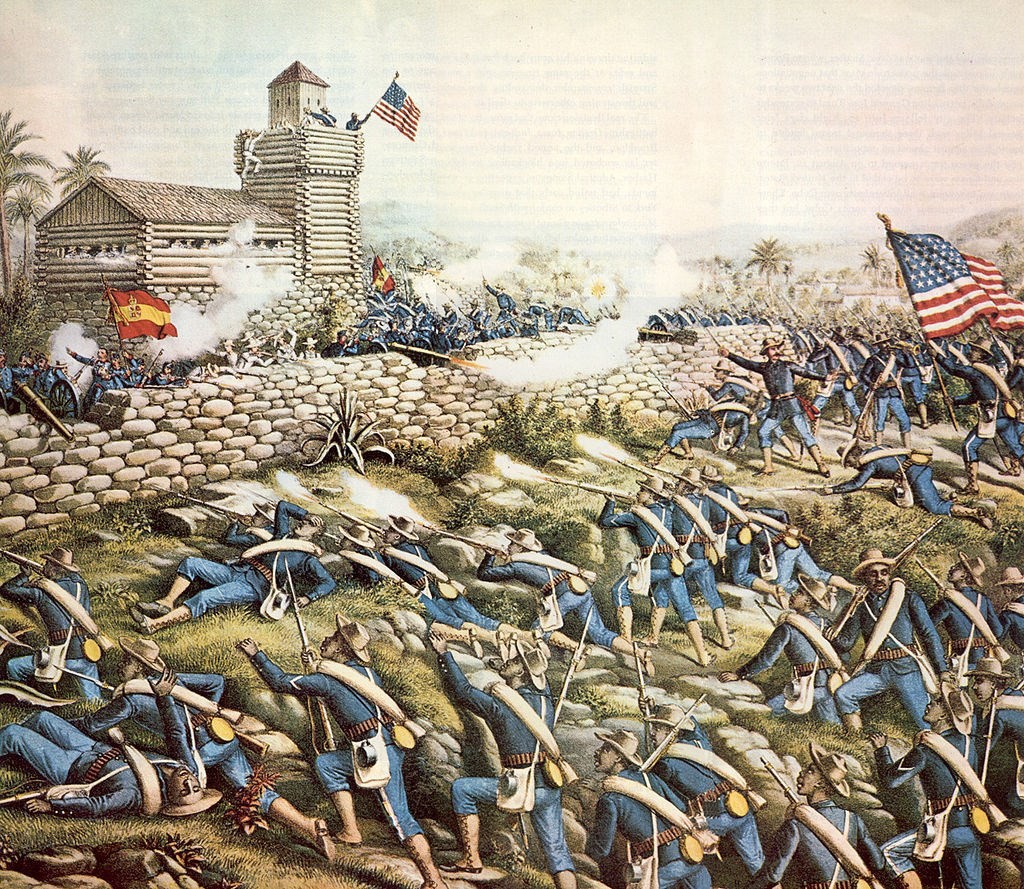

Though most of the action in the Spanish-American War took place in the Pacific Theater, Cuba saw significant naval and land-based operations. The bloodiest and best- known battle in this part of the war was at San Juan Heights, two kilometers east of Santiago de Cuba, known as the Battle of San Juan Hill. Though much of the post-battle press went to Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, as well as the first-ever use of the Gatling Gun in war, the most difficult fighting fell to the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th and 24th Regiments.

As then Lt. John J. Pershing later recalled, “White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young man-hood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederate or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans.”

For their efforts at San Juan Hill, five Buffalo Soldiers earned the Medal of Honor. These regiments would go on to fight with distinction in the Philippine-American War (1899- 1903), Mexico and World War I (1916-1918), and World War II (1944-1945). The 24th Infantry Regiment, participating in the Korean conflict, was the last American segregated unit to see battle before the regiment was disbanded in 1951.

Social Sharing