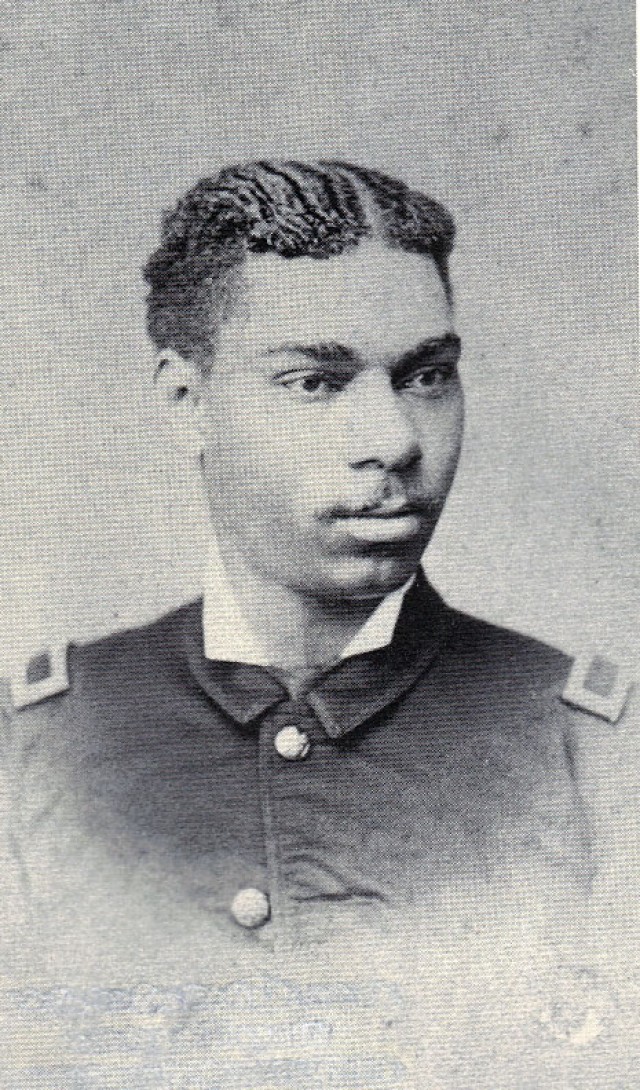

FORT SILL, Okla. (Feb. 7, 2019) -- This month marks the 20th anniversary of the one thing Lt. Henry O. Flipper most craved for the last 58 years of his life -- exoneration.

Almost 59 years after his death, it came when President Bill Clinton granted him a pardon on Feb. 19, 1999.

Flipper had been acquitted of the charge for which he was court-martialed -- embezzlement.

The charge that resulted in his dismissal from the Army was brought against him during the lengthy proceedings, perhaps after it became apparent the original charge would no longer stick.

He believed there had been a conspiracy to get him. Racial prejudice ran deep during Reconstruction, and as an African American with some Cherokee blood, Flipper often bore the brunt of it.

He won his commission as a cavalry second lieutenant on June 14, 1877, becoming the first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. In his five years in the Army he served at five historic frontier posts -- Forts Sill, Elliott, Concho, Davis, and Quitman.

FORT SILL

While serving at Fort Sill in his early 20s he executed three civil engineering projects that would prepare him for a post-Army career as an expert surveyor, mapmaker, and civil and mining engineer.

First, he surveyed the route and supervised the building of a road from Fort Sill to the railhead at Gainesville, Texas. Second, he successfully constructed a telegraph line from Fort Elliott, Texas, to Fort Supply.

His third and most memorable engineering feat was the design and construction of a drainage channel system to eliminate the malaria problem at Fort Sill.

According to historian Theodore D. Harris, "Flipper took justifiable pride in the fact that one of the officers who had previously failed to accomplish this task was an engineering graduate of Germany's Heidelberg University." "Flipper's Ditch," as it has come to be known, still controls floods and erosion in the area. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977, 99 years after it was built.

As post signal officer Flipper drilled both white and black troops in signaling techniques. He served four months as acting troop captain for Troop G when its commander left for detached duty.

Flipper saw extensive field service scouting the Llano Estacado ("Staked Plains") of west Texas; sent to find a nonexistent lake, he instead swore in a postmistress for a place called Teepee City.

He was responsible for inspecting and receiving cattle to be distributed to American Indians at the Wichita Indian Agency near Anadarko.

He also served in the military escort that removed Quanah Parker and his band of Comanche and Kiowa from the Texas Panhandle to the reservation near Fort Sill during the winter of 1878-79.

Flipper made one other important contribution while he was at Fort Sill. That was the 1878 publication of his first memoir, The Colored Cadet at West Point.

In his introduction to Flipper's posthumously published second memoir, Black Frontiersman, Harris called Flipper's first memoir "one of the earliest authentic black autobiographies in American literary history. It remains our most informative and detailed chronicle of cadet education, customs, social life, and race relations at West Point during the 1870s."

That Flipper was an astute observer of the world around him there is no doubt. A letter dated Jan. 4, 1878, describes his arrival here.

He had received orders Dec. 6, 1877, to join his company, Troop A, 10th Cavalry. At Houston he met his regimental commander, Lt. Col. John W. "Black Jack" Davidson, who informed him that his company was then at Fort Concho, Texas, but under marching orders for Fort Sill, Indian Territory.

"I was instructed from San Antonio to proceed to Fort Sill and there await my company. I went from Houston to Caddo, Indian Territory, by rail. At Caddo, I took the stage. After a very disagreeable journey of 160 miles, I reached Fort Sill Tuesday evening, Jan. 1."

He then goes on to describe the living arrangements of the cavalry barracks and the general landscape. In closing, he wrote, "Altogether the post is a good one and a pleasant one at which to be stationed."

One friend he made at Fort Sill was Lt. Henry Ware Lawton, the City of Lawton's namesake, who helped Flipper buy furniture and settle in.

Later, when Lawton was promoted, he bought a barrel of beer and sent for Flipper and another lieutenant to help him celebrate. Flipper wrote to a friend that it was "the first, last, and only time I ever drank beer. Of course, I wasted all I could and drank as little as I could and drank because of my great admiration for Lawton."

Flipper grew so fond of Fort Sill that he wept upon departure for duty at Fort Elliott, Texas,, on Feb. 28, 1879.

Flipper received good treatment while at Sill, but trouble found him after he was assigned to Fort Concho.

Initially, things went well. His Troop A commander, Capt. Nicholas M. Nolan, was the de facto commander of the fort, and he made Flipper his adjutant. But certain whites were scandalized that Flipper was invited to board with the Nolans and dine at the family table.

Worse, in their view, Flipper often went horseback riding with Mollie Dwyer, the sister of Nolan's wife, and the pair exchanged letters. These letters fell into the wrong hands and would come back to haunt Flipper at his court-martial.

In 1880, he fought with Nolan against the Apache chief Victorio and earned a commendation.

In 1881 he was stationed at Fort Davis, Texas, and assigned the duties of post quartermaster and commissary officer. Davis writes that "(it) was a responsibility for which he had no previous military or civilian experience" and it "required accountability of large sums of government funds within a complex system of Army finance."

Col. William Rufus Shafter, the commander of Fort Davis, had a reputation for harassing officers he disliked.

He didn't mind commanding Buffalo Soldiers but he objected to having one as an officer. Within days, he dismissed Flipper from the quartermaster job without cause.

Then he told Flipper the quartermaster 's safe was not secure and "asked" Flipper to keep the government funds in his quarters. In July 1881, Flipper discovered nearly $3,800 missing from his trunk. In a panic, he lied to Shafter about the shortage, hoping to buy time in which to replace the missing funds.

He wrote a personal check for $1,440.43 in an attempt to make up the shortage, but he was unable to raise money fast enough for the check to clear.

Shafter's treatment of Flipper was unduly severe. He ordered Flipper confined to the guard house; this was reversed by order of higher authority. Notwithstanding the fact that civilian supporters in the nearby community came to Flipper's aid and replaced all the missing money, Shafter preferred charges.

The court acquitted Flipper of embezzlement but convicted him of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, a charge that was added after the court-martial was underway.

He was sentenced to be dismissed from the Army, the officers' equivalent of a dishonorable discharge.

On appeal, the judge advocate general of the Army recommended the sentence be reduced, and the secretary of war approved the recommendation; nevertheless, President Chester A. Arthur confirmed the original sentence.

To the end of his days Flipper fought to clear his name. The cloud was still hanging over him when he died at the age of 84 on May 3, 1940, in Atlanta. But in 1976 the Department of the Army granted Flipper an honorable discharge. Flipper's long-sought presidential pardon at last came on Feb. 19, 1999, thanks to a Washington, D.C., law firm that did all the paperwork pro bono.

After his dismissal from the Army, writes Harris, "Flipper remained in the Southwest and northern Mexico as a civilian.

From 1883 to 1919 he earned distinction as the nation's first African American civil and mining engineer. Between 1919 and 1921 he served in Washington, D.C., as consultant to the Senate committee on Mexican relations. From 1921 to 1923 he was assistant to Secretary of the Interior Albert W. Fall."

Flipper wrote his second memoir at El Paso, Texas, in 1916 when he was 60 years old.

The manuscript was intended for a close friend of more than 35 years, a Mrs. Brown of Augusta, Ga. Flipper retired in 1931 and for the remainder of his life lived with his younger brother, Joseph Simeon Flipper, a former college president and bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

After Flipper's death, relatives donated the manuscript to the Atlanta University Library, where Harris found it and arranged for its publication in 1963.

Next: Flipper saves a town

Social Sharing