SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y.-- In December of 1917 the National Guard Soldiers of the 42nd Division were all in France, waiting for training in the trench warfare that marked World War I in Europe.

The division's 27,000 troops had started moving from Camp Albert Mills on Long Island to France in October. The last elements of the 26-state division--the 168th Infantry Regiment from Iowa-- had reached France at the end of November.

The 42nd Division had been formed by taking National Guard units from 26 states and combining them into a division that stretched across the country "like a rainbow" in the words of the division chief of staff, Colonel Douglas MacArthur.

The largest elements were four regiments from Ohio, Iowa, Alabama and New York organized in two brigades of two regiments and supporting units.

The New York National Guard's 69th Infantry, renowned as the "Fighting 69th" had been renamed the 165th Infantry.

By Christmas 1917 the division's elements were located in a number of villages northeast of the city of Chaumont, about 190 miles east of Paris. The men had hiked there from Vaucouleurs where they had originally been deposited by train.

The 165th Infantry celebrated Christmas 1917 in the village of Grand. Father Francis Duffy, the regiment's famous chaplain, celebrated a joint American-French mass on Christmas event.

According to Sgt. Joyce Kilmer, a poet, and editor, "the regimental colors were in the chancel, flanked by the tri-color. The 69th was present, and some French soldier-violinists. A choir of French woman sang hymns in their own language, the American Soldiers sang a few in English, and French and American joined in the universal Latin of "Venite, Adoremus Dominum."

On Christmas Day the men ate turkey, chicken, carrots, cranberries, mashed potatoes, bread pudding, nuts, figs and coffee. The Army, wrote Corporal Martin Hogan "was a first rate caterer."

The 168th Infantry, from the Iowa National Guard, hosted 400 French children at a Christmas celebration in the village of Rimaucourt. Two American Soldiers dressed like Santa Claus gave presents to the French children and a French band played the Star Spangled Banner. The kids received dolls, horns and balloons, recalled Lt. Hugh S. Thompson in his book "Trench Knives and Mustard Gas."

The 168th didn't eat as well as the 165th on Christmas day, according to Thompson. "Scrawny turkeys and a few nuts were added to the usual rough menu" he recalled.

The 166th Infantry from the Ohio National Guard, was reviewed by General John J. Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force just before Christmas. On Christmas they enjoyed music from the regimental band and a good meal.

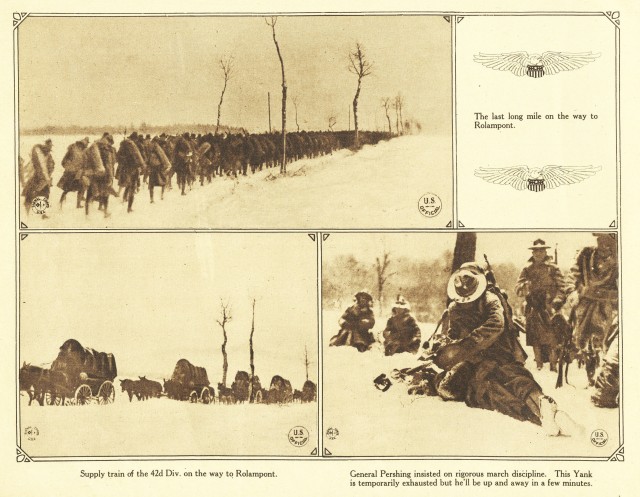

While Christmas 1917 was a good one for most Soldiers of the Rainbow Division the next week went down in the division's memory as "The Valley Forge Hike."

It was 30 to 40 miles from where the division's troops had celebrated Christmas to the town of Rolampont, where the U.S. Army's Seventh Training Area, had been established.

Today you can drive the route in an hour. In 1917 it took the Soldiers four days to get there.

The march was miserable, according to the 1919 book "The Story of the Rainbow Division."

The Soldiers had "scarcely any shoes except what they had on their feet, there was no surplus supply to speak of. Some of the men had no overcoats."

The Soldiers walked into a mountain snowstorm. In some places the snow was three to four feet deep. Soldier's shoes wore out. Some marched almost barefoot and there were bloody trails in the snow.

Lt. Thompson recalled that the men in his unit were issued hobnailed boot: the soles were held by heavy nails. The problem, he said, was that the nails got cold and the men's feet froze too.

"Bleak expanses of icey geography appeared and vanished in monotonous fields between villages," he recalled. "Legs ached, pack straps cut into shoulders, unmercifully men fell out, exhausted."

At night the men huddled in the barns and haylofts of the French villages to keep warm.

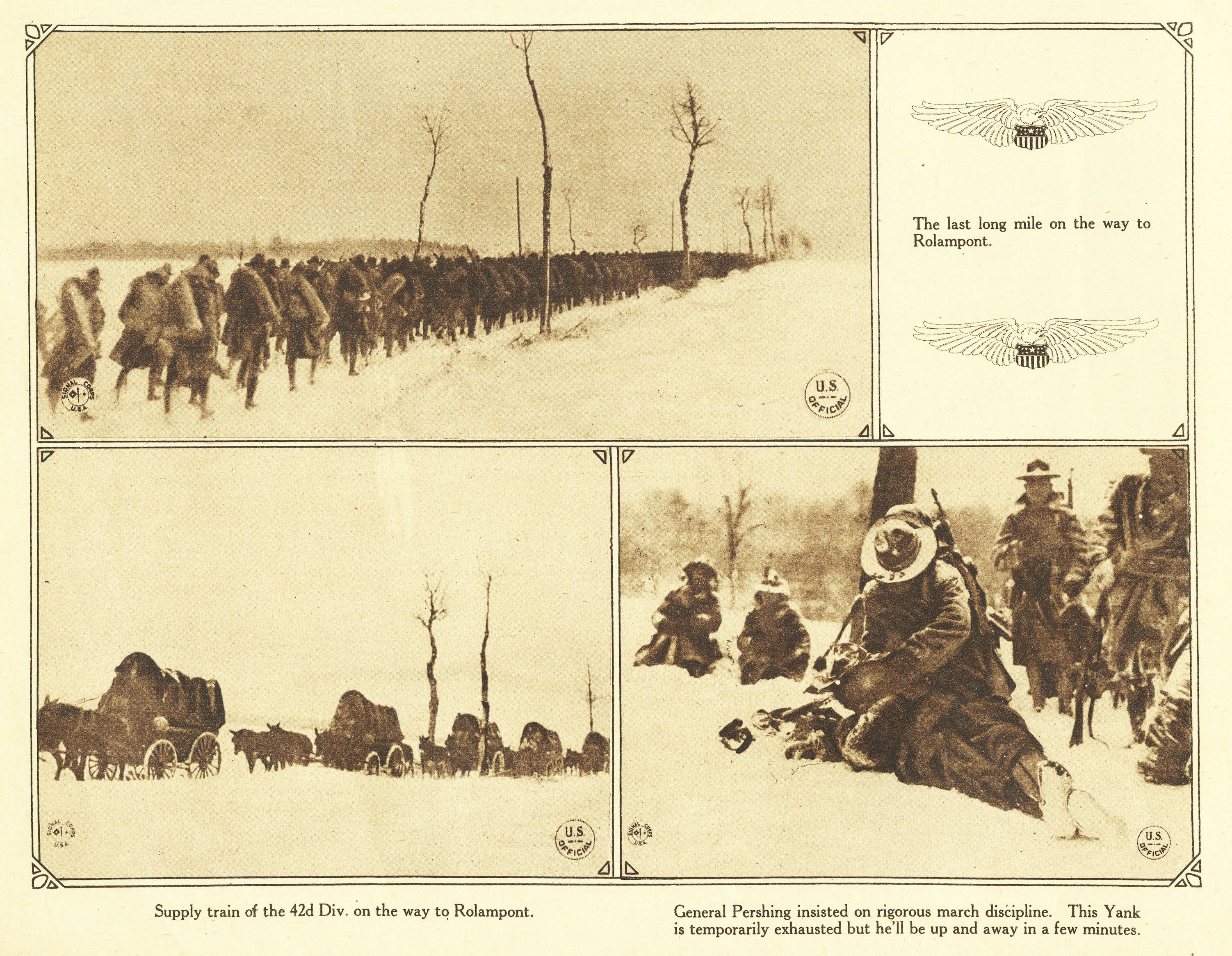

The mule and horse drawn supply wagons got stuck on the icy roads and men had to move their best animals from wagon to wagon to get them unstuck, Father Duffy recalled.

For three days the men in the 165th Infantry Regiment's Third battalion had no food, according to Kilmer, and when rations caught up to the men they got coffee and a bacon sandwich, or a raw potatoes and bread.

"The hike made Napoleon's retreat from Moscow look like a Fifth Avenue Parade," one New York officer remembered later.

"The men plowed over the hills and thru the snow, enduring hardships which are not pleasant to remember," wrote Reppy Alison, the author of a book about the 1st Battalion 166th Infantry.

Medics reported cases of mumps and pneumonia as the temperatures dropped below zero. Hundreds of men fell out-- 700 at least and 200 of the New Yorkers--but most made it to Rolampont.

As the 165th Infantry arrived, the regimental band struck up "In the Good old Summertime".

By New Year's Day the division's elements had arrived in Rolampont, and along with a new year they got a new commander.

Major General William Mann, the former head of the Militia Bureau, the equivalent of today's Chief of the National Guard Bureau, had taken command of the division at Camp Mills.

But Mann, who was 63 in 1917, couldn't meet the physical standards for officer laid down by General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force.

He was replaced by 55-year old Brig. Gen. Charles T. Menoher.

As 1918 began Menoher and the Soldiers of the Rainbow division began gearing up to go to go into the trenches.

Social Sharing