"I see her face every day of my life," Sean Parnell said.

He had just arrived at Forward Operating Base Bermel in eastern Afghanistan in February 2006 when he experienced something so horrible that it changed his life forever. Insurgents fired upon the FOB, but overshot their target, wounding and killing local children who were playing nearby.

Parnell, then an infantry officer with 2nd Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, had arrived at FOB Bermel before his platoon to get acquainted with the area. Just minutes after stepping off of a CH-47 Chinook, he found himself racing to the aid station while carrying a bleeding child.

At 24 years old, he watched a little girl die in his arms.

* * *

Just two years earlier, Parnell was hanging out with friends and preparing to graduate from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. He had transferred from Clarion University to join the school's ROTC program after 9/11.

"It's what I wanted to do," he explained. "My whole life I was surrounded by people telling me I can't do something or I wasn't good enough. I joined the Army to be in the infantry -- the light infantry -- and I wanted to be a Ranger."

The young lieutenant wanted to be face-to-face with the enemy on the front lines. Growing up listening to war stories like "Band of Brothers," left him longing to share the experiences of an infantry officer and the bond that grows between men in combat.

"My career early on was defined by youthful idealism," Parnell said, laughing. "I really didn't know what the hell I was talking about, but I wanted to do it nonetheless."

His platoon, nicknamed the Outlaws, had been training for two years to prepare for their 2006 Afghanistan deployment -- running between 20 and 30 miles a week.

"Tactically, we were all over it; we were ready to rock," Parnell noted. "(However), the U.S. military was so largely focused on the growing counterinsurgency operations in Iraq that we couldn't glean any intelligence on the Afghan front."

"On one hand, we were really well-trained, physically fit and we were ready to 'kick ass and take names,' but on the other hand, we didn't know the enemy that we were facing," he continued.

Leading B Company's 3rd Platoon, Parnell and his unit were expecting an ill-equipped force in Afghanistan, but what they found was a war-hardened group of fighters who had been fighting -- or training for combat -- since the 1980s.

During Outlaw Platoon's 16-month deployment, the unit experienced hard-fought battles, some of which Parnell said he wasn't sure they would survive. In addition, the injuries, both physically and mentally, took a heavy toll on his men.

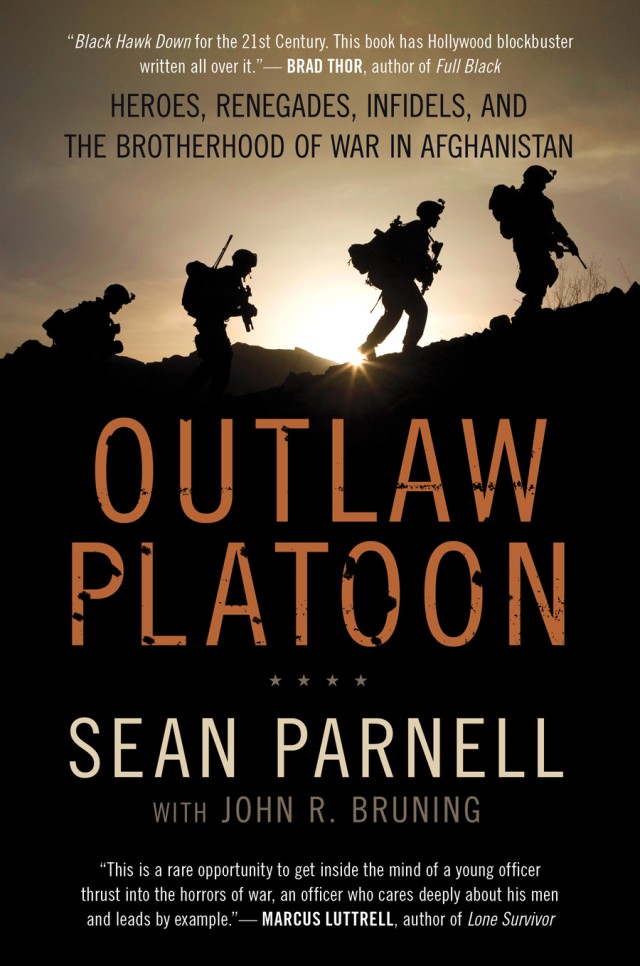

His deployment and the bond he shares with his Soldiers inspired him to write a book. "Outlaw Platoon: Heroes, Renegades, Infidels, and the Brotherhood of War in Afghanistan," which outlines his experiences leading 3rd Platoon's deployment, was released by Harper-Collins last week.

"The main reason I wrote the book … was I promised (my men) that I would figure out a way to tell their story," Parnell explained. "Largely, because I felt they were overlooked. Nobody in America knew the extent of the war in Afghanistan (at the time we were deployed)."

Military units in Afghanistan faced a high injury rate and were attacked regularly, he added.

"My men would go home on leave and people would (say), 'Thank God you're not in Iraq. It's safer in Afghanistan.' And my men are like, 'What do you mean? I just got shot in the head last week,'" Parnell said.

Parnell, who earned a Purple Heart and Bronze Star for valor during the deployment, returned home with shrapnel in his leg and a traumatic brain injury that left him with vision problems, migraines and caused cerebrospinal fluid to leak out of his ears and nose throughout the last half of the deployment. He refused to seek treatment until after the unit returned.

Aside from his physical ailments, Parnell faced a darkness that had metastasized inside. In the book, he writes about trying to maintain his humanity.

"I struggled with being a human being in an inhumane environment," he said. "Combat veterans come back forever changed. The innocence and distance that you once knew in the United States is burned away forever in your first experience in combat. For me, it was a little girl."

After handing the lifeless child back to her parents and returning to his room, Parnell had removed his bloody uniform, which he had been wearing since he left Fort Drum, and changed into a clean set.

"Having to burn my bloody uniform out in the burn pit was a (real-life) metaphor for my stateside skin being burned away while simultaneously being replaced by the hardened skin of a combat veteran," he said. "That's when the metamorphosis (began)."

Writing down his experiences and telling his Soldiers' stories allowed Parnell to continue to heal.

"There's something about taking the war out of myself and putting it on a page that was hugely therapeutic," he explained. "Most warriors join (the military) because they want to protect the society that they've sworn to defend."

When service members begin telling war stories to their civilian friends and Family Members, it's a "buzz kill," according to Parnell. Veterans realize their stories hurt and scare the loved ones they have sworn to protect, so Soldiers stop telling stories and begin lying to protect them.

"(When they realize this), they lock the war away inside them, and that is toxic; it erodes … from the inside out," he said. "For me, writing the book was cathartic, because it's out there now. Our story is out there."

Now medically retired, Parnell is pursuing a doctorate in psychology at his alma mater in hopes of helping fellow veterans.

"I want to be there for them, but also I'd like to help them tell their stories, either by giving them the tools or courage," he said.

Parnell hopes his book will inspire other veterans to tell their stories.

"I think their stories need to be told, but more than that, they need to be heard," he added. "Everybody in the United States needs to know (veterans' stories). The burden of war does not simply rest with those who fight it on the ground. The burden of carrying the hardships of war falls on the society itself.

"It's society's duty to learn and understand what combat is like for young veterans coming home," he continued. "So often in life we're faced with the easy wrong or the easy right, but owning these wars (and past wars) is the hard right. Just listen."

Social Sharing