The Fiscal Year 23 Mission Command Training in Large-Scale Combat Operations Key Observations publication states that units routinely struggle to develop a complete operational framework. Furthermore, units lack processes to adjust their operational framework in contact based on current conditions.1 During Warfighter Exercise (WFX) 25-1, the 1st Armored Division (AD) staff experienced similar challenges. The term battlefield framework in this article refers to the use of graphic control measures, specifically boundaries, that delineate responsibilities at echelon. Through 1AD’s experience at WFX 25-1, the division staff found that they must understand the factors that impact the positioning of forward and rear boundaries, develop their battlefield framework during planning, and communicate boundary refinements with their higher headquarters and subordinate units.

VIEW ORIGINAL

The Operational Framework in Doctrine

Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, describes three models commonly used to build an operational framework: 1) assigned areas; 2) deep, close, and rear operations; and 3) main effort, supporting effort, and reserve.2 Although 1AD uses aspects of all three models in its operational framework, this discussion focuses on the division’s use of assigned areas and deep, close, and rear operations.

There are three types of assigned areas units may use: area of operations, zones, or sectors. Defined by its boundaries, an area of operations is “an operational area defined by a commander for the land or maritime force commander to accomplish their missions and protect their forces.”3 Zones are areas assigned to units in the offense that only have rear and lateral boundaries.4 Finally, sectors are operational areas assigned to units in the defense that have rear and lateral boundaries and interlocking fires.5

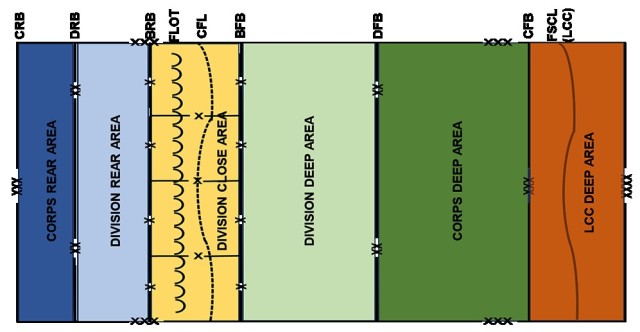

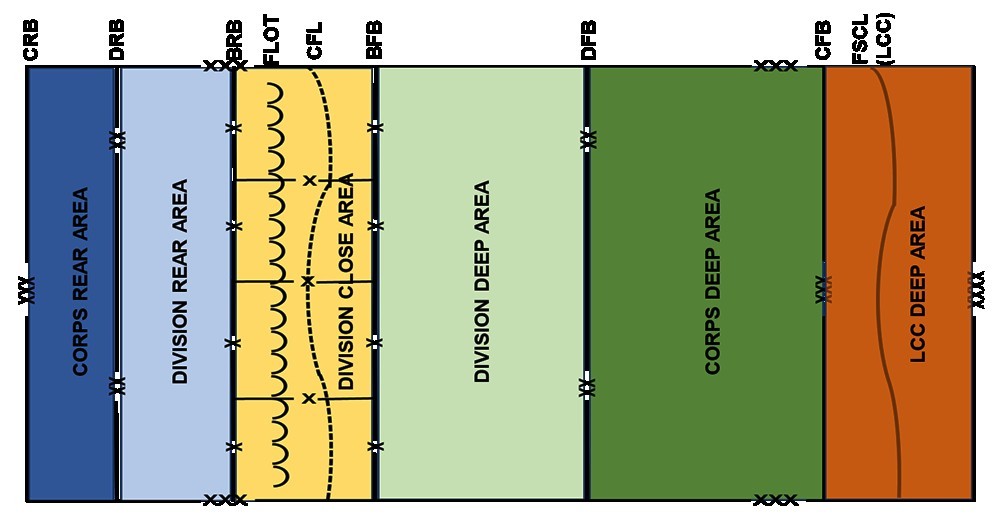

During its division-level National Training Center (NTC) rotation in January 2024, 1AD used a mixture of zones and sectors to define subordinate units’ operational areas. Using zones and sectors, the division defined its deep area as the area between the division forward boundary and the coordinated fire line (CFL). The close area was defined as the area between the CFL and the brigade rear boundary, and the rear area was defined as the area between the brigade rear boundary and the division rear boundary.

Several months later, the division transitioned to exclusive use of areas of operations in its WFX 25-1 training progression. In the areas of operations model, the forward and rear edges of the deep and close areas changed. Integrating a brigade forward boundary, the division’s deep area became the area between the division forward boundary and the brigade forward boundary. The close area became the area between the brigade forward boundary and the brigade rear boundary.

The key difference between 1AD’s use of the assigned areas models is the type of control measures used to define the deep and close areas. Using zones and sectors, 1AD defined its deep and close areas with a mix of control measures and fire support coordination measures (FSCMs). Once transitioned to areas of operation, 1AD used only control measures to define its deep and close areas. The transition occurred because doctrinally FSCMs are not intended to delineate responsibilities between units. According to FM 3-09, Fire Support and Field Artillery Operations, FSCMs “enhance the expeditious engagement of targets; protect forces, populations, critical infrastructure, and sites of religious or cultural significance; and set the stage for future operations.”6 The CFL, which was 1AD’s measure separating the division deep from the division close, is a permissive FSCM that is used to facilitate the expeditious attack of targets, not to assign responsibility for the attack of targets.

Once again, the key control measures used to delineate the deep, close, and rear areas of 1AD’s operational area are boundaries. A boundary is “a line that delineates surface areas for the purpose of facilitating coordination and deconfliction of operations between adjacent units, formation, or areas.”7 It is also important to note the responsibilities inherent to units assigned an area of operations, which are: terrain management, information collection, integration, and synchronization, civil affairs operations, movement control, clearance of fires, security, personnel recovery, airspace management, and the minimum-essential stability tasks.8 These doctrinal responsibilities must be considered when determining placement of the forward and rear boundaries. However, subsequent sections of this article focus on the finer aspects corps and divisions must account for when determining deep, close, and rear areas.

Forward Boundaries

When using areas of operations to assign areas, forward boundaries form the far edge of a unit’s area of operations. At the corps and division levels, the forward boundary is the start of the respective echelons’ deep area.9 A unit’s deep area is not assigned to a subordinate maneuver element and is where the establishing commander is responsible for designating target priority, effects, and timing. Further, the establishing commander plans and controls execution of all operations conducted in their deep area. An echelon’s forward boundary is established by their higher headquarters — the division forward boundary is established by the corps, and the brigade forward boundary is established by the division. Thus, corps are responsible for operations forward of the division forward boundary, divisions are responsible for operations from the division forward boundary to the brigade forward boundary, and brigades are responsible for operations up to the brigade forward boundary.

Typically, deep operations occur or have their effects in the deep area. FM 3-0 defines deep operations as “tactical actions against enemy forces, typically out of direct contact with friendly forces, intended to shape future close operations and protect rear operations.”10 The manual goes on to list several activities conducted as part of deep operations, which are: deception; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and target acquisition; interdiction; long-range fires; electronic warfare; offensive cyber operations and space operations; and military information support operations.11 Organically, corps and divisions are not able to execute all of the listed activities conducted as part of deep operations. However, when organized appropriately for operations, both echelons can either execute with task-organized forces or with assets available from adjacent units or the joint force. Forward boundaries at the corps and division level delineate where each echelon is responsible for these deep operation activities.

In most cases, brigades do not have a true deep area nor are they task organized to conduct deep operations. Brigades operate in the division’s close area and conduct close operations, which are “tactical actions of subordinate maneuver forces and the forces providing immediate support to them, whose purpose is to employ maneuver and fires to close with destroy enemy forces.”12 Activities supporting close operations include maneuver of subordinate formations, close combat, indirect fire support, information collection, and sustainment support of committed units.13 Close operations occur from the brigade forward boundary to the brigade rear boundary, and many of the activities conducted as part of close operations occur or effect from the forward line of own troops (FLOT) to the brigade forward boundary.

There are three factors corps and divisions must consider when determining the placement of forward boundaries. First, units must consider their operational approach. Part of the operational approach is understanding three fights: the current fight, the next fight, and the fight after next. Second, corps and divisions must account for the range of the delivery systems task organized at echelon. Corps must understand the range of their assets as well as the range of their divisions’ assets, and divisions must understand the range of division and brigade assets. Finally, units require an understanding of their subordinates’ information collection capabilities. When considering these capabilities, staffs must understand not only the systems conducting information collection but the organizations responsible for processing, exploiting, and disseminating the intelligence products derived from the information collection systems. Without an understanding of these factors, corps and divisions may establish forward boundaries up to which their subordinate formations cannot truly affect.

The operational approach may be the most important factor to consider when determining the placement of a forward boundary. A way for corps and divisions to conceptualize their operational approach is by compartmentalizing the current fight, the next fight, and the fight after next. Generally, brigades are responsible for the current fight, divisions are responsible for the next fight, and corps are responsible for the fight after next. Under this concept, the brigade forward boundary delineates the current fight and the next fight, and the division forward boundary delineates the next fight and the fight after next. These “fights” may be based on objectives or enemy formations if it is clear, at echelon, who is responsible for what objective or enemy. Using this framework, corps, divisions, and brigades can easily understand where their effects, lethal or non-lethal, need to be focused. This framework also assists in understanding what conditions must be set for the subordinate echelon to assume the fight. When a unit understands what objective or enemy formation they are responsible for affecting, they can focus their information collection and effects and develop appropriate, conditions-based triggers for the shifts of the forward boundaries.

The second factor to consider when determining forward boundaries is the delivery capability of the subordinate formation. The placement of the division forward boundary must account for the range capability of the artillery and aviation systems available at the corps and division levels. If the corps’ and division’s artillery capability is the same, the division forward boundary may be closer to the FLOT to allow corps to range the objective or enemy formation that is the fight after next. Similarly, the corps staff must understand the range capability of the corps’ and division’s aviation assets. For both artillery and aviation, corps must also consider ammunition available at echelon. Even if a subordinate division has the range to affect a deep division forward boundary, it may not have the ammunition available to create the effects required to set the conditions needed for the next fight. When placing the brigade forward boundary, the division staff must understand the forces available for each brigade with a forward boundary. When the division weights its main effort with a field artillery battalion, or two, there is a chance that another brigade does not have direct support (DS) artillery. In that case, the brigade forward boundary for the brigade without DS artillery should be closer to the FLOT than it is for the brigade with one or two field artillery battalions. Understanding delivery capabilities at echelon requires routine dialogue between corps, division, and brigade staffs. Higher headquarters must allow subordinates time to provide feedback on the placement of their forward boundaries.

Finally, staffs must consider information collection capabilities and capacity at echelon. Usually, the intelligence sections at each echelon have the means to access the intelligence products from National Reconnaissance Office overhead systems (formerly referred to as national technical means). However, not all intelligence sections are created equal. Corps and divisions have robust analysis and control elements (ACE) that possess greater ability to perform processing, exploitation, and dissemination (PED) of information. Due to recent changes to the Army’s force structure, brigades no longer have an organic brigade intelligence support element (BISE), so the PED capacity at the brigade is reduced. Staffs must consider the PED capacity of their subordinates when assigning areas of operations to ensure their subordinates can execute effective information collection. The capability of corps, division, and brigade-controlled information collection assets must be considered when determining forward boundaries. Corps and divisions typically control assets that can collect tens of kilometers from the FLOT brigades; however, they may not have the same capability. Staffs need to understand the capability of the information collection assets task organized to the brigade before determining the brigade forward boundary. Like delivery capabilities, staffs at echelon must engage in routine dialogue about information collection capabilities to inform the placement of forward boundaries.

Placement of boundaries define fights at echelon. The “three fights” framework — current fight, next fight, fight after next — is a way to understand and articulate who is responsible for what objective or enemy formation. Additionally, staffs must consider their own and their subordinates’ effect and collect capabilities. If these factors are not given serious consideration, units risk assigning too much, or too little, area to their subordinates for deep and close operations.

Rear Boundaries

FM 3-90, Tactics, states that the rear boundary delineates the rearward limits of a unit’s assigned area and defines the start of the next echelon’s rear area.14 The rear boundary sets the area from which the organization conducts rear operations, usually defined as the area from the organization’s rear boundary to the rear boundary of the next echelon. Additionally, FM 3-0 defines rear operations as tactical actions behind major subordinate maneuver forces that facilitate movement, extend operational reach, and maintain desired tempo. During WFX 25-1, some of the requirements in the rear area included retaining lines of communication (LOC) for resupply operations, opening a ground LOC in support of host nation governance, and securing forward arming and refueling points (FARP) and critical assets in addition to enabling the division’s offensive tempo. The division was required to balance security operations in the rear area with an increasingly expanding rear area, given limited combat power and few options to task organize additional combat power. The division had to identify how to allocate its forces over a large area and prioritize requirements. Additionally, the division learned the necessity of delineating clear roles and responsibilities between command posts and activities in the rear area. As a result, the division identified the necessity for establishing an authorities matrix that clearly delineates responsibilities for each command post. For missions that fall within the purview of the rear command post, there must also be a clear hand off from planners in the main to those in the rear. Furthermore, planners must fully acknowledge the capabilities for span of control when setting the rear boundaries and identify risk with mitigation measures.

During WFX 25-1 the division assigned the maneuver enhancement brigade (MEB) with security tasks in the rear area, with an M777 battery providing general support (GS) fires, a Stryker battalion assigned as the tactical combat force, and the deputy commanding general – support (DCG-S) as the rear area commander. At the start of the exercise, this was sufficient to accomplish tasks in the rear area. However, as the division progressed forward in its operation, the division’s rear area continued to expand. One of the division’s challenges with the rear area is that the rear boundary is set by its higher headquarters. This necessitates the coordination with corps to shift the division rear boundary. However, corps faced similar challenges regarding limited combat power and its ability to secure an expanded rear area. Therefore, our recommendation is to codify a procedure for the corps and division to identify requirements and articulate risk for its rear area in conjunction with potential shifts of forward boundaries.

Challenges and Pitfalls

During WFX 25-1, planners made planning assumptions regarding our probable line of contact. During wargaming, we assessed a likely probable line of contact that was medium or deep within our assigned area in relation to our initial objectives. However, we failed to consider that Donovian forces would beat us to our initial wet gap crossing, and therefore our plan lacked the flexibility to account for a shallow meeting engagement. The resulting impact of this planning shortfall was a battlefield framework that did not sufficiently enable the division to set the conditions prior to our initial wet gap crossing and ultimately resulted in a 48-hour delay and considerable losses in combat power. We learned that the battlefield framework is vital to enabling the division to set the conditions for the division’s critical events. Therefore, the battlefield framework must have the flexibility to enable deep operations in support of each critical event prior to subsequent framework shifts. Moreover, any shift in the framework must be tied to clearly articulated conditions that must be met to enable subsequent movement of the division’s deep, close, and rear areas.

A second aspect that we struggled with was setting a battlefield framework that optimized the ability for the division to effectively set conditions in the deep area while also providing an appropriate area for subordinate brigades to execute their operations in the close area. Furthermore, the corps assignment of our division forward boundary quickly extended beyond the division’s ability to set conditions. Therefore, this required division-to-corps requests for modification of the boundary or division-to-corps coordination for the establishment of kill boxes to effectively shape. Additionally, the division could not set a brigade forward boundary that extended too deep for the brigades to own without appropriate division shaping. Our recommendation is that the shift of the battlefield framework must be tied to conditions that are set by each echelon. Conditions should be identified during planning and modified within the future operations (FUOP) cell. The movement of the battlefield framework should be tied to a trigger with codified conditions that will be met to initiate the shift. Key considerations for the division to shift its battlefield framework include an assessment of the correlation of forces and means. Additionally, divisions should work with corps to establish a method to adjust the battlefield framework and confirm shifts during execution.

Conclusion

The establishment of the battlefield framework can be visualized spatially using objectives identified on the map. It can then be visualized temporally using the three fights framework. From there, the division can establish boundaries that enable conditions setting in the deep area in preparation for the next brigade close fight. These boundaries must also provide the space for the brigades to fight in the close area and current assigned objectives, and a rear area that allows for the division to maintain its tempo and sustain itself. It is critical for each echelon to understand the capabilities and limitations of their formations when assigning boundaries to ensure subordinate elements can collect, effect, protect, sustain, and maneuver. Units that fail to establish a complete battlefield framework that is understood at echelon may experience similar challenges and pitfalls that create confusion, inhibit tempo, and fail to exploit opportunities.

Notes

1 Carl Fischer, ed., FY23 Mission Command Training in Large-Scale Combat Operation Key Observations, March 2024, Center for Army Lessons Learned, 1, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2024/03/07/f3684ca2/24-03-853-mctp-fy23-key-observations-mar-24-public.pdf.

2 Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, October 2022, 3-23.

3 Ibid., 3-24.

4 Ibid., 3-24.

5 Ibid., 3-24.

6 FM 3-09, Fire Support and Field Artillery Operations, August 2024, B-1.

7 FM 1-02.1, Operational Terms, February 2024, 8.

8 FM 3-0, 3-24.

9 Army Techniques Publication 3-94.2, Deep Operations, September 2016, 1-8, 1-2.

10 FM 3-0, 3-29.

11 Ibid., 3-29.

12 Ibid., 3-29.

13 Ibid., 3-30.

14 FM 3-90, Tactics, May 2023, A-6.

MAJ Nathan Schoffer currently serves as the chief of Future Operations, 1st Armored Division (AD), Fort Bliss, TX. His previous assignments include serving as a plans officer, 1AD, Fort Bliss; commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment (AIR), 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, NC; and commander of D Company, 2-325 AIR. He is a graduate of the Command and General Staff Officers Course with a Master of Operational Studies, Fort Leavenworth, KS, and earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from Central Washington University and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Georgia.

MAJ Jeremy Maness currently serves as a fires planner for 1AD. His previous assignments include serving as a plans officer for 1AD Division Artillery (DIVARTY); commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 10th Mountain DIVARTY, Fort Drum, NY; and commander of A Battery, 2nd Battalion, 15th Field Artillery Regiment, Fort Drum.

This article appears in the Summer 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it.

Social Sharing