FORT LEE, Va. — The “Adams” in Fort Gregg-Adams — Fort Lee's future name — pays tribute to the military service of a Women’s Army Corps officer who, among other achievements, successfully led the all-Black 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion during World War II.

Fort Lee’s re-designation is part of a congressionally mandated action to remove Confederate names from federal properties. The April 27 official renaming ceremony also honors retired Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg, the first Black American promoted to lieutenant general in the U.S. Army.

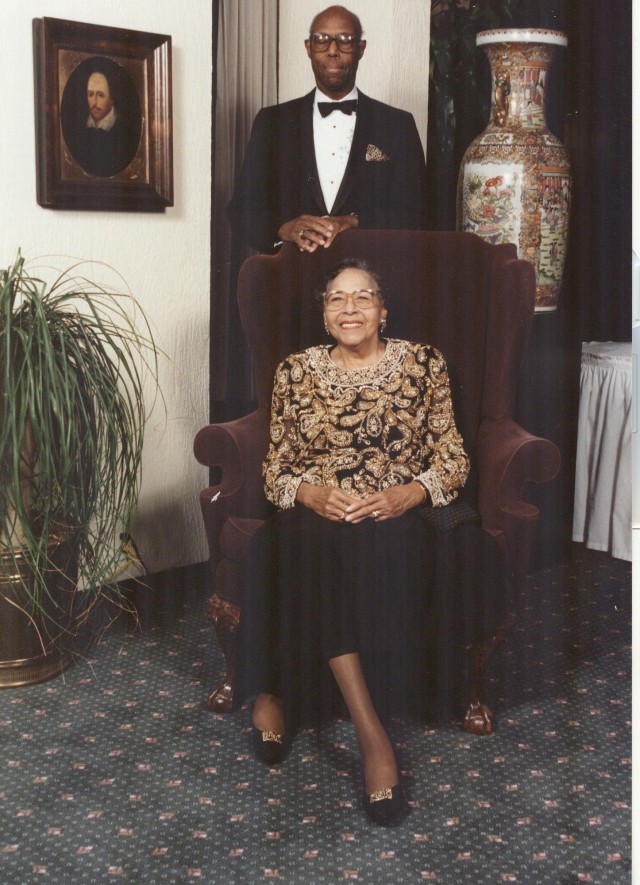

In the case of Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the tribute is similarly focused on her military career, but certainly acknowledges the Columbia, S.C., native’s life and contributions beyond her four-year stint in uniform. That includes her marriage to Stanley A. Earley Jr., and her extensive work to uplift others.

Granted, Mrs. Earley’s post-military life did not achieve the notoriety of running an overseas postal operation under segregated conditions during war — the stuff of documentaries, an upcoming movie and countless news articles. It is, nevertheless, a chapter worthy of remembrance.

So says Stanley Earley III, the 71-year-old son of the late Charity Adams-Earley and Stanley Earley Jr.

Understandably appreciative of the attention surrounding the installation’s renaming, the Maryland resident said, by default, his mother’s eventful, albeit short, Army career overshadows more than 50 years of what she did afterward.

Foremost in that assertion is Adams’ relationship with the man she married in 1949. Stanley Jr. was a trailblazer of another sort, and his achievements could stand on their own, said his son, the budget director for Prince George’s County, Maryland.

“My father was a very intellectual, very thoughtful person,” said Stanley III, noting his many talents.

The senior Earley met Charity Adams in the late 1930s at Wilberforce College, a historically Black institution located in Ohio. The Dayton native later transferred to Ohio State University, eventually earning an engineering degree. Figuring he would be drafted for military service, Earley enlisted in the Army as a translator, having learned French in high school. He also became fluent in German.

“My father had a real gift for languages,” Stanley III recalled, noting his dad later learned Russian and Spanish.

During the war, Stanley Jr. worked with German prisoners of war, helping them “get back to their families,” his son said. The work was profound, as the senior Earley remained in Germany and stayed connected with several POWs long after the smoke had cleared. A portrait of one such individual was discovered hanging on his father’s wall shortly before his death in 2007 — yet another testament to his language skills that served as a portal to worlds beyond himself.

The Adams and Earley paths converged sometime after WWII, said Stanley III, but he is not sure when. She completed her master’s degree at Ohio State University and took several jobs, including three at institutions of higher learning, according to her memoir, “One Women’s Army, A Black Officer Remembers the WAC.” He, on the other hand, applied for medical school abroad as many such U.S. institutions then would not admit Black people.

“At the time he went to medical school,” said Stanley III, “there were very few options for African Americans … in the United States. There was Howard (University) and Meharry (Medical College) and Columbia (University) was open about admitting people. There were a few others, but only a very limited number of spots were available.”

The meager options made it worthwhile to seek opportunities in Europe where he was familiar with the cultural landscape, said Stanley III. His dad applied to and was accepted at two prestigious schools in Switzerland.

“He (eventually decided upon) the University of Zurich, a German-speaking medical school (and) one of the best in the world at the time,” Stanley III said. “He was also admitted to the University of Geneva, which is French speaking.”

In the meantime, Mrs. Earley learned German through the Minerva Institute and later studied for two years at the University of Zurich and the Jungian Institute of Analytical Psychology. Stanley Jr. earned his degree and subsequently departed Germany with his pregnant wife in 1952.

Upon returning to the states, Stanley Jr. completed his residency at New York City’s Harlem Hospital. The family returned to Dayton afterward, and he became Dr. Stanley Earley, a general practitioner who provided medical care there for more than 40 years.

“He was really respected in the community,” said Stanley III. “To this day, I could be walking around Dayton and people would come up and say, ‘your father delivered me’ or ‘your father was the person who gave me my physical exam so I could play on the football team.’ … He had a great impact on public health.”

Mrs. Earley also made her presence felt in the community. After daughter Judith was born, she went about like a Soldier on a mission. She sat on the boards of many organizations including the Dayton Chapter of the American Red Cross; Sinclair Community College; Dayton Metro Housing Authority; and Dayton Power and Light Company.

She also volunteered for the National Urban League, YWCA and United Way. Additionally, Mrs. Earley was the founder of the Black Leadership Development Group and co-founder of Parity, a local equity and diversity advocacy group.

Together, the couple supported various Dayton arts and cultural institutions and sowed seeds to support community interests in perpetuity.

“Money is only a piece of giving,” Stanley III said in the fall 2019 edition of the Good News online publication. “Part of being a good citizen is to stay involved. My parents were active volunteers for many organizations and very involved in church. They believed you should share in improving the community in which you live.”

As community supporters, the Earleys were cognizant of what their example meant to others, and did much in preparing those of future generations, especially their children, said Stanley III.

“I can remember sitting together at dinner as a family,” he said. “They’re talking about issues in the community, and I remember them bringing my sister and I into the discussions. ‘OK, what’s the best way to approach this problem?’ Each of them tried to assist in thinking through what the other was suggesting. That was our dinner conversation.”

Aside from their family life and livelihoods, the Earleys — although complimentary as partners — had widely different interests, said Stanley III. His father was an audiophile who loved the arts and classical music. His mother, described by her son as “loquacious,” enjoyed playing ping pong, viewing Star Trek and watching baseball games.

“There were things each other liked, but they sort of made space for each other,” their son reflected. “Each got their turn at going to the place they wanted to go. For example, my father would (attend and) watch baseball games, but he made sure he bought his music.”

Although Mrs. Earley had served in the military and achieved wide notoriety, Stanley III said she was not focused on the past as much as she was on contemporary matters. As a result, he did not realize the significance of her accomplishments until he was in college.

Later, certain events reinforced what was learned about his mother’s military time over the years, said Stanley III. One such encounter included President Bill Clinton and Gen. John Salikashvili, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, at a 1990s-era Daughters of the American Revolution ceremony.

“Gen. Shalikashvili gave my mother a terrific introduction, of which my mother was very proud,” he recalled. “Then my mother introduced President Clinton. She was a really good speaker and gave one of her best speeches. It was really nice and really funny, too.”

Earley’s speech moved Clinton to demonstrate his own comedic skills, said Stanley III.

“So … he came up to the podium and said, ‘I have to decide — I don’t want to put a damper on the evening — whether to dismiss or demote the person who said I have to speak after Col. Earley.’ She really liked that. She was always very proud of that event. She was incredibly honored …”

The DAR ceremony was a shining moment for Dr. Earley as well, watching it all unfold with prideful veneration.

“My father was very proud of my mother,” said Stanley III. “He was pleased whenever she received recognition.”

Undoubtedly, Dr. Earley would be pleased beyond measure with the honor and recognition associated with the name change that will soon become official here, said Stanley III.

“He’d be very excited about this,” said his son.

Not to mention his mother — the Soldier who oversaw precious letters delivered in an overseas theater of war, and who, like a Soldier, trudged on long and hard, waging countless battles in the name of humanity.

“I think she’d be a little bit astounded, but she’d be proud,” said her son.

Of what might be her shiniest moment of recognition from a proud U.S. Army.

Social Sharing