During my visits to units around the Army, I noticed that one particular sustainment brigade stood out as having the best process to manage talent. This brigade put together deliberate sessions with all command team leaders present from the brigade, battalions, companies, and platoons.

These leaders looked at the skill sets and character traits of every officer and noncommissioned officer. They identified those who were strong in certain skills and those who needed additional training. They then matched officers who had a particularly strong skill or trait with noncommissioned officers who were not as strong in that area, and vice versa, to complement one another.

This kind of pairing makes those units collectively better and ensures talent is equal across all formations. It prevents one unit from having all A-plus players and another all B-minus players. The results could be seen in the readiness of their units. In all measures they were higher than others in the Army.

The thing that stands out most in my mind is that the sustainment brigade got to the heart of what talent management is really all about: making units better.

Individuals should be involved in their own careers, but they should think in the context of what is best for the unit and Army. No matter the assignment, they should do the best they can.

As retired Gen. Colin Powell says in his book "It Worked For Me: In Life And Leadership," "Great leaders inspire every follower at every level to internalize their purpose, and to understand that their purpose goes far beyond the mere details of their job."

This article discusses three more talent management refinements that we can make to ensure we have the right individuals who can excel at the jobs the Army gives them.

EXPERIENCE

First, let's put people in higher level jobs only if they have the right experiences. During the past 17 years of war, we have tried to create a broader officer corps, which has been important. We have provided opportunities for officers to broaden their experience base, which also has been important. But what I have observed is that, to some degree, we have gone too far with prioritizing diversity of assignments over mission.

The result has been not having the right individual with the best skills in place, especially in battalion command positions and jobs after battalion command. In my view, we should be very selective; for division-level positions, we should choose people who have served in divisions before. The skills, techniques, relationships, and expertise to be successful at that level are achieved only by having served in a division at more junior levels.

If we bring officers without experience and put them into that environment, they will be disadvantaged from the beginning and potentially could lose credibility with peers and senior leaders. The outcome may not be the best. It is critical we manage people based on their skills and put them in positions that allow the organization to benefit most from those skills.

Of course, with our younger officers, especially lieutenants and captains, we should continue giving them diverse assignments, including division and non-division experience. They should be able to build their skill sets in various functional and multifunctional areas. This will make them more competitive when they reach the field-grade level and will enable them to become better commanders at the battalion and brigade levels. But it is incumbent upon us to match the skills of the officer with the position that can best benefit from his or her experience.

Likewise, with our noncommissioned officers, we have to pick the most qualified and put them in the right positions at the right time. In today's high-operating-tempo environment, where we are fighting on multiple fronts and potential high-intensity conflicts are on the horizon, we cannot afford to have organizations assume risk because we are trying to train an officer or noncommissioned officer for a particular position.

MENTORSHIP

Second, individuals need to change how they think about mentorship. Too many noncommissioned officers and officers are looking for a particular person who will give them some particular insight. They are not seeing that mentors are all around them. Any engagement with a senior leader is a mentoring session. You do not need a personal relationship with a leader in order to receive his or her guidance and advice.

Some people want mentors who have similar backgrounds, either in career field or military experience. The problem is that you limit yourself by choosing that type of a mentor. You are not going to learn all you need to know from an individual who is too similar to you; they will not teach you diversity of thought.

You need to look for different types of mentors, in different fields, of different ages and demographics. Otherwise you won't have the breadth of knowledge implanted through diversity of backgrounds and experience to make tough decisions.

If you are a mentor, you need to be honest with those you mentor. Don't tell them what you think they will want to hear. When I talk to young officers, I share with them my experiences. But my experiences as a lieutenant, captain, and major were totally different from what we expect from our lieutenants, captains, and majors today. So what I recommend is that they talk to officers who have more recent, relevant success. If you are a young captain, talk to a major; and if you are a major, talk to a lieutenant colonel.

I also encourage officers and noncommissioned officers to take positions that make them uncomfortable. If you are comfortable in a position or doing the same type of jobs, then you are not challenging your abilities and growing. You are not learning new capabilities and techniques to be successful in the future.

IMPERATIVES

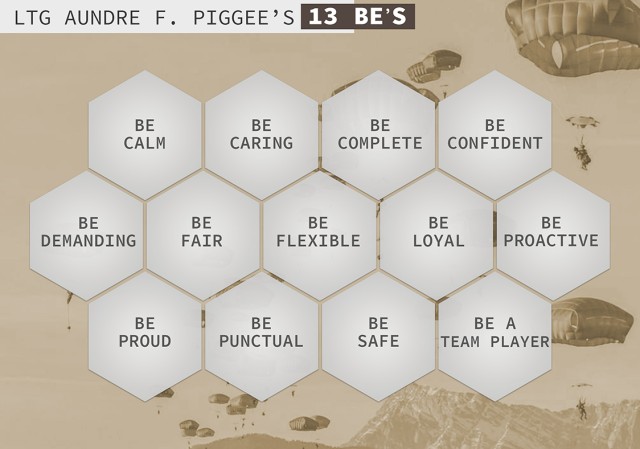

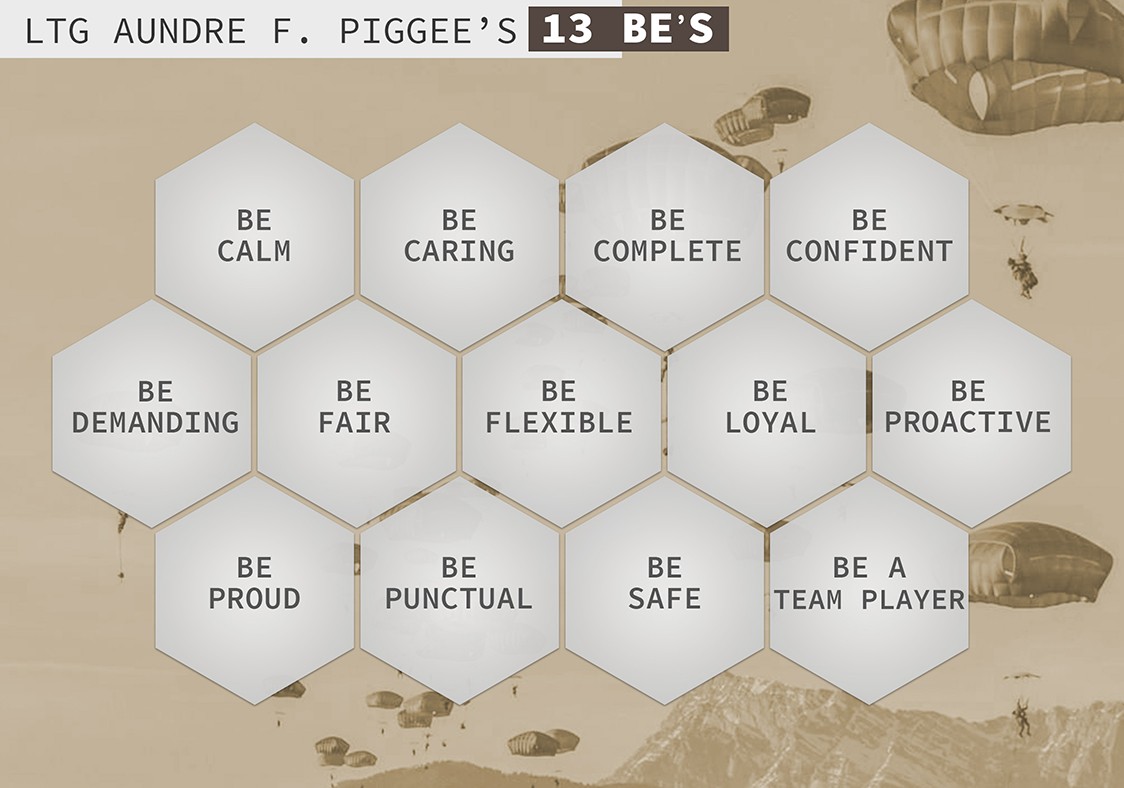

Third, develop imperatives that will improve your skills and make yourself more valuable to your unit. I have my "Piggee Imperatives." I call them the 13 Be's. (See figure 1.) This is not a checklist of what will make you successful on a daily or weekly basis. It is a compilation of skills and values I have found over the course of my 37 years of service that have allowed me to be successful in any environment, situation, or command climate. I used these imperatives at the battalion and brigade levels and when I was commander of the 21st Theater Sustainment Command.

It starts with being committed--committed to your profession, committed to your career field, and committed to your organization.

It is okay to be demanding, but I think we should also be calm. Be proud of the organization you are part of. Care for those you supervise.

It is okay to be confident, but remember there is a thin line between confidence and arrogance. A high level of confidence is expected from our Army leaders and, more importantly, from those Soldiers we lead.

Strive for perfection. No Soldiers should be satisfied where they find themselves. Our goal is to better ourselves every day. Even though we may have been successful yesterday, we should not be satisfied with what we accomplished yesterday. We should still strive to improve our situation, our stance, our unit, and the Soldiers we lead every day.

Learn from your mistakes. Good leaders underwrite mistakes as long as they are not unethical, illegal, immoral, or unsafe. We should forgive and use mistakes as learning opportunities. We should allow our subordinates to fail while managing risk. If you are not failing, you are not trying something new. You are not being innovative. You are just settling for the status quo.

In the end, individual mentoring and individual imperatives go hand in hand with the Army's decisional factors for who should get what jobs and how many people we should have doing certain tasks. Focusing on the right combination of experience, expertise, and diversity of thought will improve talent management, which will improve our units, build readiness, and make our Army stronger.

--------------------

Lt. Gen. Aundre F. Piggee is the Army deputy chief of staff, G-4. He oversees policies and procedures used by all Army logisticians throughout the world.

--------------------

This article was published in the July-August 2018 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Browse July-August 2018 Magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing