ROCK ISLAND ARSENAL, Ill. - When Lt. Gen. Michael S. Tucker retires this summer, one of the longest and most diverse careers in Army history will come to a close.

The Charlotte, North Carolina, native joined the Army 44 years ago as a private, and has since served as a drill sergeant, tank commander in combat, battalion commander, brigade commander, armor school commander, Walter Reed Army Medical Center deputy director, division commander, and First Army commanding general.

While he has been entrusted with such vital missions as caring for wounded service members and veterans, and overseeing the training of every Army National Guard and Army Reserve unit in the continental United States, Tucker came into the Army with a much more modest goal: seeing what was beyond Charlotte.

"I joined the Army in March of 1972 to do one tour and get out," Tucker said. "I wanted to see the rest of the world. I was raised in Charlotte, never moved, and had never really been anywhere."

His homeroom teacher also happened to be the Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps instructor. "He had a poster that showed a tank commander sitting on top of his tank, and it said, 'Join your local track team,' referring to the tank's tracks. I looked at that picture and said, 'I want to be that guy, and I want to command one of those massive beasts.' In August, I reported to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, on a Greyhound bus."

Tucker's first day of basic training was "a shock," he said. But he made it through, and even though he had originally intended to get out after his initial three-year enlistment, the Army had boosted Tucker's confidence and vision.

"I didn't know I had potential, but the Army saw potential in me. I didn't have a plan for me, but the Army had a plan for me," he said. "What intrigued me was the Army wouldn't allow you to get complacent. The Army forced you out of your comfort zone and challenged you."

At a U.S. military education center in Germany, Tucker saw a poster that said 'Be All You Can Be.' He remembered thinking, "Are you all you can be, or are you what you want to be?"

"The Army was challenging me," he said. "I was supposed to get out in 1975, and the reenlistment [noncommissioned officer] is crawling all over me because I'm a clean kid. There were a lot of guys doing dope in the barracks back then, a lot of guys smoking hash. The Army in the mid-70s was not exactly a pretty Army. There were 'blanket parties', there were people taken to the woodshed.

"But the Army kept challenging me, and they made me an acting sergeant. I took [a military occupational specialty] test and scored high enough that I got another $150 a month. And I'm thinking, 'This isn't too bad, I'm kind of liking this.' So I reenlisted for two years."

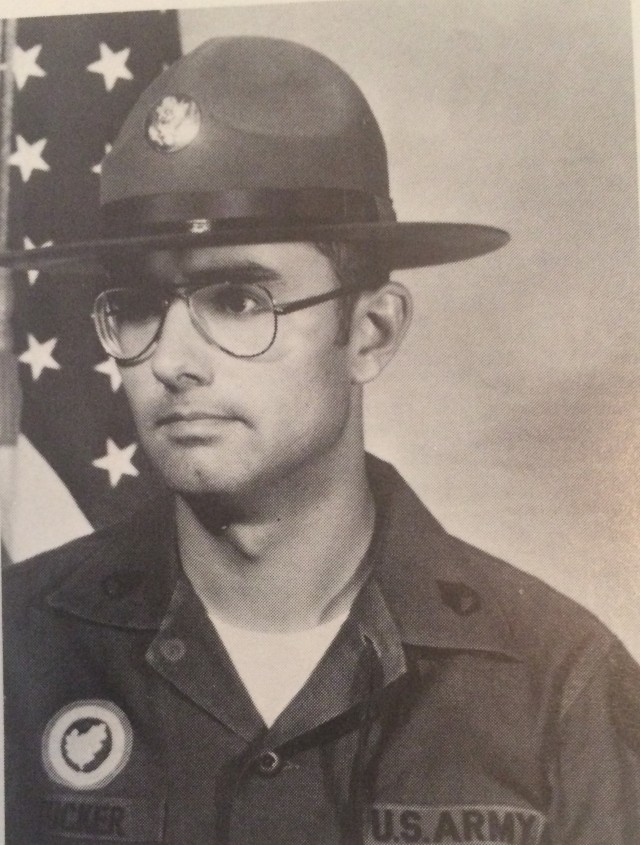

Before long, he was selected for drill sergeant duty, which he described as one of his most rewarding experiences.

"You take those kids, who can't even do an about face without falling over, who don't know how to salute, who don't know how to talk Army, and you turn that civilian into a Soldier. There was unequaled job satisfaction."

After two years of turning raw recruits into Soldiers at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, Tucker went to Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Just as he had as an enlisted troop, he made rank quickly as an officer; eventually, he was assigned as commandant of the U.S. Army Armor School.

The young man whose ambition was sparked by a poster on a classroom wall had gone from a private being ordered around by drill sergeants, to being the drill sergeant, to being the two-star general in charge of the drill sergeants.

Tucker's nearly seven years of enlisted time has been invaluable throughout his career, allowing him to see things through the lens of a young private, a specialist, a sergeant, a staff sergeant, and a sergeant first class, he said. "Every time I've made decisions that affect them, I've looked at it through their lens, and it's given me a very clear picture.

"When I was Armor School commandant, I would see that a drill sergeant was getting worked up," Tucker recalled. "Training has made him really angry, and that happens. Trainees can really touch your buttons. What we did, we'd walk up to a drill sergeant, pat them on the back, and say, 'Hey you've got a phone call.' And that means, walk away. You've got to have a way because it can get abusive. I saw some drill sergeants that were abusive to trainees back in the mid-70s, and there's no place for that."

Tucker had joined the Army to be part of a tank crew, but the service also gave him the unexpected benefit on an education.

"I was only 17 and I didn't do that well in high school. I was a vocational arts kind of guy, working on cars," Tucker recalled. But an education counselor asked him if he wanted to go to college.

"And I said, 'I could go to college?' No one in my family had ever gone, and I didn't know about my grades. He asked me where I went to high school and said he'd send for my transcripts. Two weeks later, he tells me, 'We can get you signed up for the University of Maryland.' And I was hooked.

"In high school, I didn't care about that stuff. I wanted to get out and do things and fix stuff. Now I couldn't wait to do my homework, and I wanted to turn in my papers.

Once I got one class done, I wanted another."

Tucker's leadership encouraged his studies, an example he followed when he became a leader himself.

"We were in the field, and the first sergeant would take me to class at night, then back to the field. I never asked him to; he allowed me to do that and took away that hurdle," said Tucker, who later made sure that Soldiers under his command would have the same opportunities.

"When I was a battalion commander…I allowed Soldiers to go to school on Tuesdays and Thursdays from [3 to 6 p.m.]," Tucker said. "They couldn't be placed on any duty that would prevent them from going to classes. The NCOs were all over me, and I said, 'I know what goes on in the motor pool at 1500, platoon sergeant. It's sweeping and tying off tops. You'll just have a few less people to push brooms. We'll be fine.'"

The policy took off, he said.

"We went from about 12 Soldiers in school to about 250, in a 600-man battalion. They were motivated, they showed initiative, they showed discipline. While other Soldiers were out partying, they were working on papers, they were studying, they were in the library. All the attributes you look for in leadership, they were displaying. Then, when we're doing boards for Soldier of the Quarter and Sgt. Audie Murphy Club, it was these guys being selected."

As he rose in rank and could influence even more Soldiers, Tucker continued to champion education.

"When I was a brigade commander in Germany, I've got 5,000 troops, and we had 2,800 Soldiers going to school. It was terrific," he said. "When I was a division commander in Korea, I had 3,800 Soldiers going to college. Article 15s and discipline incidents dropped 54 percent, reenlistment went through the roof, and all because you gave a Soldier a chance to do something for themselves that no one could ever take away.

"So every time I've been in a situation to give back, I've done it. I joined the Army right out of high school, and I have an undergraduate degree and two master's. The Army allowed me to be all I can be. I am thankful for the Army for giving me the opportunity it has."

Tucker had moved up quickly through the enlisted ranks during his first several years of service, but then was given the opportunity to go to Officer Candidate School, which meant giving up a probable command sergeant major position someday to start over as a second lieutenant. When he decided to try OCS, he discovered that he often knew more than the instructors.

"I had just come off being a drill sergeant for two years, and I was a good drill sergeant. I had been Drill Sergeant of the Cycle four times. The first couple of weeks at OCS, I'm being pushed around by second lieutenants that were waiting to get into the infantry course," Tucker recalled. "A lot of the things they were saying were wrong. It wasn't in line with the [Field Manual]; they'd give commands wrong.

"I thought seriously, 'I've made E-7 in six years, nine months, I'm 23 years old, I'll be a sergeant major, maybe I should go with that,' but my roommate talked me out of it."

Tucker received his commission and today is the Army's senior-ranking OCS graduate. Just as he had as an enlisted troop, he made rank quickly as an officer.

As a major, Tucker found himself with the 1st Battalion, 35th Armor Regiment in Basra, Iraq, during Operation Desert Storm. The unit participated in Medina Ridge, the largest tank battle in U.S. history.

"We destroyed 187 tanks and 200-some armored personnel carriers," he recalled. Tucker's tank crew destroyed five tanks on the move, in the rain, from a distance of 3,000 meters.

It was training for a war that never took place that prepared Tucker to excel in Desert Storm. While stationed in Germany, Tucker's armor unit was the first line of defense against a potential Soviet invasion.

"We were trained for going up against the Soviet Union, so our gunnery fighting was five-to-one. You've got to hit five of them, and you've got to hit them quick."

Qualifying on the tank gunnery ranges and keeping the tanks maintained was "everything," Tucker said.

"You had to take care of your tank, and you didn't miss. If you didn't qualify your tank, you probably wouldn't be a tank commander in a week. Everything we did was preparing to fight the Soviets," he said.

The training was so intense that he once spent 53 straight days in the field practicing individual and collective tank skills. Also, the unit was on continual alert.

"Only 15 percent of the company could be gone at any time," Tucker said. "If you wanted to go to Christmas in the States, you better have your leave request in by February."

He also recalled regular drills in which the battalion received notice that it had two hours to be in position and fully ready to fight. "I ran over the back gate of that motor pool four times because somebody couldn't get the key, and I had three minutes left to get out," Tucker said. "I poured a lot of concrete to put the pole back, but I wasn't going to be late."

Tucker's time in armor units remains one of his greatest memories of the Army, and the mindset he acquired there has stuck with him.

"The fundamental skill set of being a Soldier was honed in me: pre-combat checks, troop-leading procedures, being aware of the maintenance of your vehicle, excelling at gunnery because you've done your homework. Those things have resonated with me in every job I've had."

Despite the demands of being a tanker in Germany, Tucker found time to be on the U.S. Army Europe ski team, competing in the biathlon.

"It was brutal," he recalled. "We didn't have a rack for the rifle; it was just kind of slung across your shoulder, so every time you advanced, your forward assist button would go across your spine."

During practice, ski team members had to complete two loops around a 10-kilometer track, in addition to trying to shoot five balloons at the halfway and finish points. Each miss meant a 50-meter penalty lap.

"We hadn't zeroed the weapons, and you can't tell where a bullet hits in the snow," Tucker said. Also, breath control is crucial to firing a rifle, and competitors were breathing heavily after 10 kilometers of Nordic skiing. So Tucker decided to just "lie down and shoot five quick shots and get up and do my penalty laps to save time."

In his final role in uniform -- First Army commanding general -- Tucker faced the challenge of managing major changes to the unit's mission and structure.

"The biggest challenge was adapting First Army so it could better execute its mission and remain relevant to the Army in terms of producing readiness. We were a very post-mobilization centric formation," Tucker said. "The Army Chief of Staff tasked me to shift First Army's focus from exclusively post-mobilization to pre-mobilization. We still do post-mobilization, we'll always do that. But it's gone from over 90,000 Soldiers a year to about 25,000 a year."

During Tucker's tenure, First Army changed its mission statement to reflect that the unit works with Reserve Component units instead of dictating to them.

"We took out words that said 'certify', 'verify', or 'controller' and exchanged them with 'partnering', 'assisting', and 'coach'," Tucker said. "We had developed a culture of meeting units at the mobilization site, telling them 'You're not adequate, you can't measure up, so we'll put you through the wringer and get you ready to deploy.' It has taken the better part of two years to win back their trust, and we're there."

From the beginning to the end of his career, Tucker has worn sixteen ranks: private to lieutenant general. Each of them has had its rewards and challenges.

"I saw opportunity in every one," he said. "With rank comes responsibility. At a certain point, you don't need to ask permission. If what it is that you need to accomplish the mission is not illegal, immoral, or unethical, why aren't you doing it already?

"I've also learned the value of follow-up. Whenever you find out that something wasn't done, somebody hadn't followed up. If the ammunition didn't show up at the range or chow is late, it hadn't been followed up. It's like telling your kids to do their homework. Doing homework is something they know how to do, but if you don't follow up on it, it might not get done."

Tucker's career has been so long that someone who joined the Army on the silver anniversary of his first enlistment will be eligible for retirement next year. The journey that has taken him from private to three-star general will end when he relinquishes command of First Army on July 15. His immediate retirement plans are to spend more time with his grandchildren, and he is considering several civilian job offers.

Social Sharing