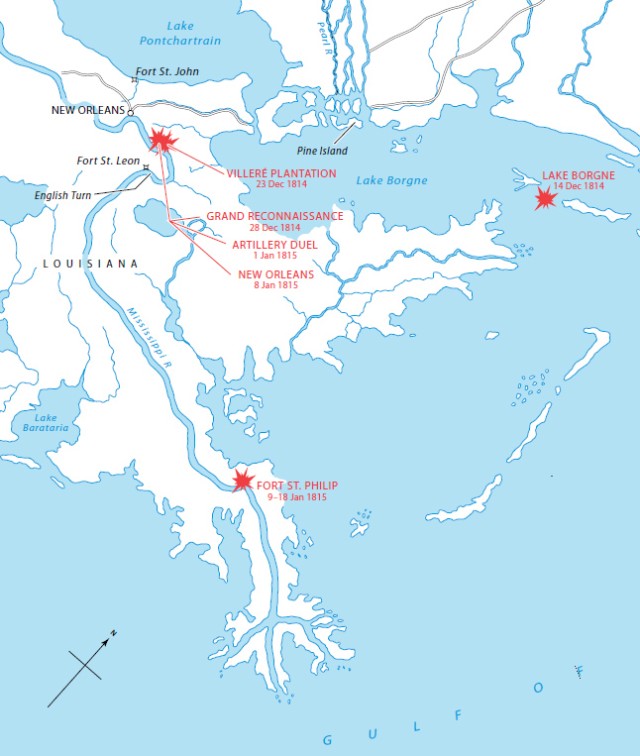

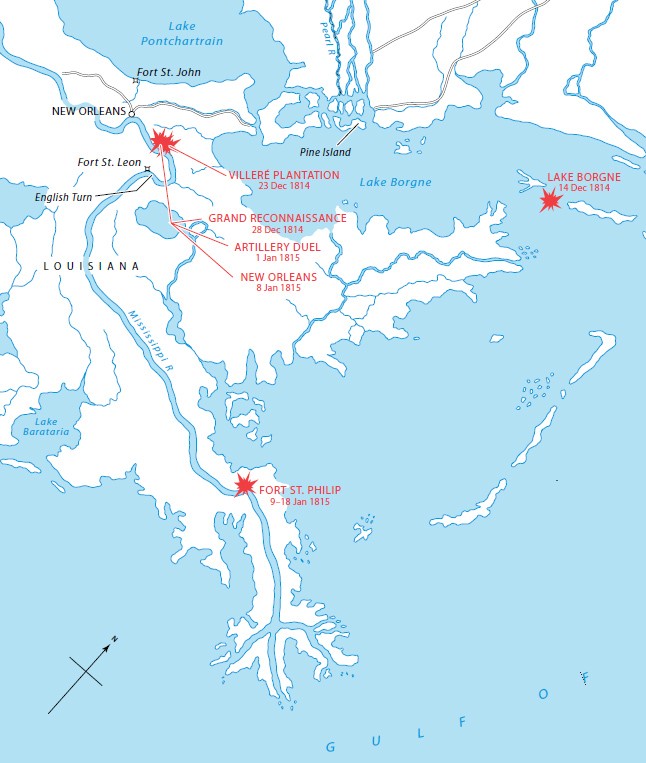

WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Jan. 8, 2015) -- The British never sailed up the Mississippi River during the Battle of New Orleans, fought 200 years ago, Jan. 8, 1815, according to a senior historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History.

Instead, they came up through Lake Borgne, an estuary of the Gulf of Mexico, then across the bayous, said historian Glenn Williams.

Further, the Battle of New Orleans wasn't just one engagement, but at least five. And, unlike many school history textbooks state, the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 was not ratified before the Battle of New Orleans, Williams said. It was not ratified by both nations and peace proclaimed until Feb. 18, 1815, a month and a half after the battle.

Gen. Andrew Jackson, the overall commander of the battle, gets most of the fame, especially since he later became president. However, Presidents William Henry Harrison, Zachery Taylor, John Tyler, and James Buchanan were all also veterans of the War of 1812.

"William Henry Harrison also won several battles in the West, which we don't remember," Williams explained: the Siege of Fort Meigs in Ohio; the Battle of Thames in Upper Canada, now Ontario; and, recaptured Detroit. The Battle of Thames resulted in the death of the great Shawnee chief Tecumseh. The "West" at the time, referred to the area now known as the Midwest.

Taylor was a captain, commanding a company that occupied Fort Harrison, a post in West Indiana Territory that withstood a pro-British Indian attack.

Jackson gets all the credit for the Battle of New Orleans, because he had better public relations, Williams said, in jest. Actually, Jackson, then a major general, commanded the 7th Military District, which included New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. That made him the overall commander.

Jackson and his military staff suspected that the British might target New Orleans, following their Chesapeake Campaign, Williams said, providing some background.

On Sept. 13, 1814, the British fleet bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Americans today know of that failed action to take the fort because Francis Scott Key wrote about it in "The Star-Spangled Banner."

After the Chesapeake Campaign, which included the burning of Washington, D.C., the British weighed anchor and debated whether to attack Newport, Rhode Island, or go south to New Orleans, according to Williams. They chose the latter.

New Orleans was selected as the prize because it was a large seaport on the Gulf of Mexico, as well as a river port for most of the farm produce in the Midwest, which got to market via the Mississippi River through New Orleans, as a rail and road network wasn't yet in place, he said.

Another intent, Williams said, was to limit American expansion to areas east of the Mississippi. "They also wanted to set up an Indian buffer state between the U.S. and British North America," he said.

COMBATANTS FACE OFF

Facing the Americans during the battle were British naval and land forces and their Indian allies. Spain, although a British ally in the war against Napoleon, was "nominally" neutral in the conflict against the United States, Williams said. East and West Florida still belonged to Spain, which feared U.S. annexation of their colony.

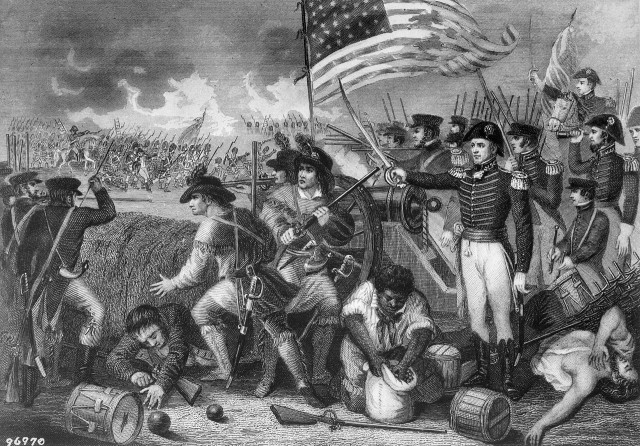

On the U.S. side, the Choctaw Indians were allies, along with French-American Jean Lafitte's Baratarian privateers.

In all, there were around 4,700 U.S. forces, facing about 9,000 British, not counting British sailors on ships in the Gulf.

The British won the naval Battle of Lake Borgne, and "technically" at least one of the land engagements. When Jackson tried to attack the British camp at the Villere Plantation on the night of Dec. 23, 1814, the British "retained the field. Although Jackson punished them pretty good, the British got reinforcements so he pulled his troops back" to a more defensible position on a nearby canal, he continued.

Next, the British attacked Jackson's forces in the so-called Grand Reconnaissance engagement of Dec. 28, which wasn't a decisive battle.

On Jan. 1, the British commenced a massive artillery cannonade. "If they had been able to breech the parapet that the Army engineers had built along the Rodriguez Canal, they would have attacked with infantry, but the attack failed," Williams said.

The last British option was the Grand Assault, most of it on the east bank of the Mississippi, with a supporting attack on the west bank, south of New Orleans. The battle never actually reached the city, he said.

LESSONS LEARNED

The Army wasn't really prepared to go to war during the first months and years of the War of 1812, which commenced on June 18, 1812, Williams said. Battles were lost during the early days and the Americans were dismayed.

By 1814, "the regular Army was really, really good," he said. "On par with the British army," considered among the world's best. The militia by this time was also fairly well trained and units throughout the South streamed down to New Orleans and participated.

By militia, Williams said there were the volunteer militia, similar to the current National Guard, and the enrolled militia, which is every able-bodied male, 18 to 45, aka draftees. Most at New Orleans were volunteer militia. Some of the drafted militia guarded the city.

The takeaway from the battle, Williams said, is that the U.S. fielded a pretty good combined-arms effort, with sailors and marines fighting on land, in coordination with regular Army and militia units. "Inter-service cooperation was excellent." As well, there was good coordination with the Choctaw allies and with Lafitte.

"Often overlooked, the Louisiana militia also had a few battalions of 'free men of color,'" he said. Some were refugees from the Caribbean and some were mixed blood creole-African Americans. "Both were heavily engaged in the battle."

Another plus for the Americans was fighting behind well-prepared positions, Williams said.

As for the British, the Royal Navy didn't send enough of their big guns to reinforce their artillery to breech those defenses, he said. They also underestimated the competence of the militia, which fought best from behind prepared positions.

AFTERMATH

Before the Battle of New Orleans, the U.S. had taken over Mobile (now in Alabama), as well as attacked Pensacola, both in what was then West Florida, mainly to keep the British from using the latter as a base from which to attack the U.S., Williams said. Spain ceded the rest of Florida to the U.S. in 1819, realizing it was indefensible.

Spain had never recognized the U.S. acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase from France, he said. Napoleon wasn't supposed to sell it to the U.S. and Great Britain didn't recognize any treaty Napoleon had signed.

Many historians think that had the British won the Battle of New Orleans, they may have probably given the Louisiana Purchase back to the Spanish, Williams pointed out.

Incidentally, the Battle of New Orleans was made famous in 1959 by the song written by Jimmy Driftwood and recorded by Johnny Horton, titled: "The Battle of New Orleans." It made the "Billboard" No. 1 song for that year. Despite the error in the song about the British running "down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico," Williams said it was his favorite song when he was 6 and he still likes it today, historical inaccuracy or not.

All of CMH's War of 1812 series can be downloaded from: http://www.history.army.mil/catalog/index.html or ordered for purchase in hard copy from the U.S. Government Printing Office bookstore.

The Battle of New Orleans pamphlet, "The Gulf Theater: 1813-1815" by Joseph F. Stoltz III will be available in a few days.

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService, or Twitter @ArmyNewsService)

Social Sharing