WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Feb. 24, 2014) -- During the 1960s, the Army and the rest of American society were grappling not only with an unpopular war in Vietnam, they were also trying to come to terms with race relations.

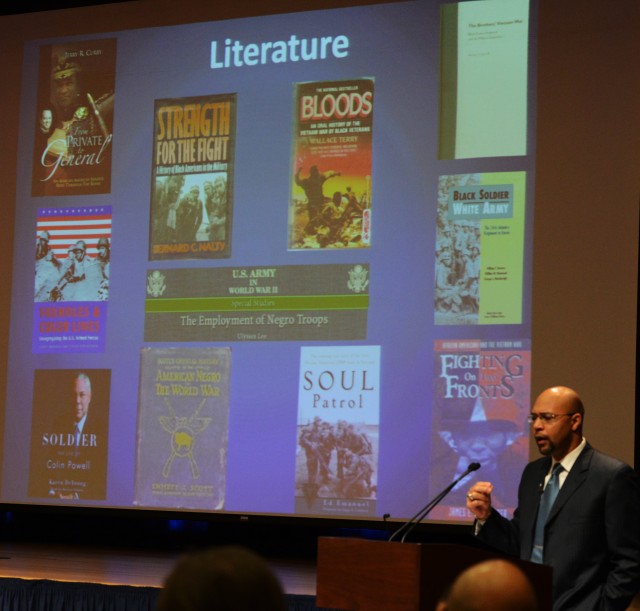

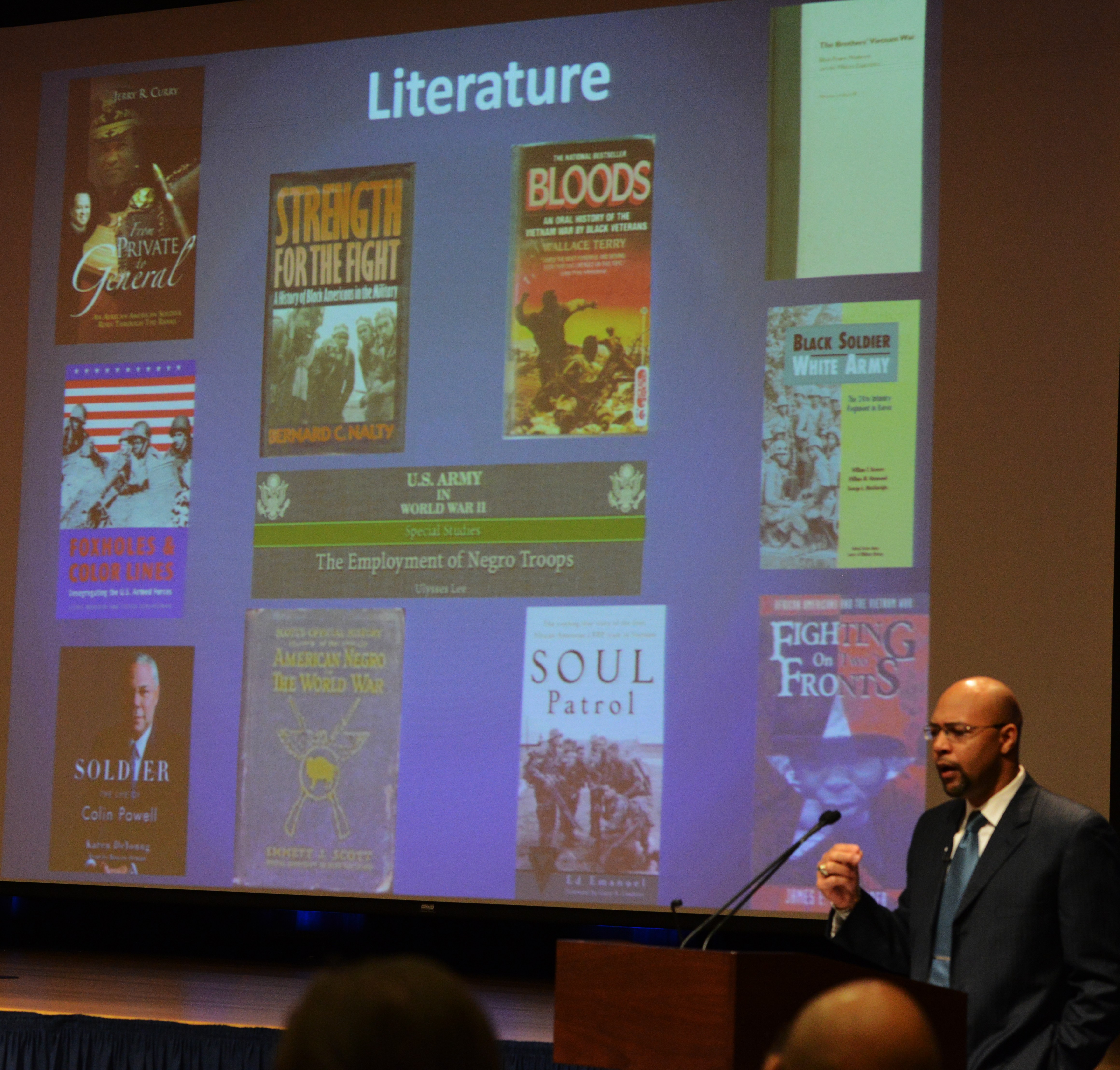

During a Feb. 24 seminar at the Pentagon, Dr. Isaac Hampton II discussed race relations in the Army during the 1960s and early 1970s, primarily as it related to African-American officers.

Hampton, an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University in San Antonio and command historian at U.S. Army South, conducted countless interviews with Vietnam-era Army veterans and also did an in-depth review of retired Army Col. Douthard Butler's research in 1971, known as "The Butler Report."

Butler, an Army fixed-wing pilot and mathematician, had been commissioned by the Army to do a study on equal opportunity.

Hampton said Butler amassed thousands of officer evaluation reports, known as OERs, from the 1950s to the early 1970s, and performed statistical analysis on trends and patterns. OERs play a main role in promotions and assignments so their composition carries enormous weight.

What Butler found, Hampton said, was a great disparity between OERs for Caucasians and those for African-Americans, with the latter being rated an average 10 to 15 percentage points below white Soldiers. In many cases the result "was devastating to their careers," Hampton said, citing a number of cases.

Derogatory comments on African-American OERs were common he said, citing several:

-- "Capt. Lionel Jackson is a good-looking, athletic officer, always out front during PT. Looks sharp in uniform."

-- "Maj. Jack Johnson is a competent officer when not drunk."

-- "This intelligent negro officer needs a high level of supervision."

Most of these comments, he said, didn't speak to leadership abilities that would have opened the doors to promotions and professional education opportunities.

Butler himself was subjected to discrimination after returning to the United States from a successful tour in Vietnam. At first he was told he'd get command of a battalion. Later, he was denied this opportunity.

When he asked the reason why, Hampton said Butler, then a lieutenant colonel, was told he had "a weak early file."

At the time, Hampton said, the Army was using a "total man concept" that looked at an officer's total career from second lieutenant onward.

The so-called "weak early file" meant that OERs done earlier in Butler's career, when discrimination was even more rampant, followed him around.

As to why the disparity in OER ratings, Hampton said a shift in culture can take time. OER raters in the 1960s had mentors who were in the Army in the 1930s and '40s -- an era when overt discrimination was the norm.

As well, he said, there were a lot of "segregationist" hold-outs in the Army during that time who thought African-American officers should not be in leadership positions.

Lastly, he said there were not a lot of African-American graduates from West Point and top-tier universities, because at the time, it was a lot harder to get in.

Changes finally came to the OER process following Butler's report, Hampton said. The changes were helped along by the newly created Congressional Black Caucus and by civil rights legislation enacted during the Johnson and Nixon administrations, including Affirmative Action.

The fallout from the OER disparity continued into the 1970s during the drawdown from Vietnam and the creation of the all-volunteer force, he said.

Many African-Americans felt disillusioned by the system. Army enlisted Soldiers too felt similar impacts in ratings, he said.

African-American enlisted Soldiers simply didn't trust their officers and thought black officers were co-opted by the system. That trust led to a breakdown in the fabric of the military. Race riots, even on installations, resulted.

The impact of the discrimination was felt especially keenly by wives of black Soldiers, Hampton said. He had said he made it a point to interview Soldiers' wives as well during his research.

The wives of African-American Soldiers, particularly in the southern states, faced the prospect of sending their kids to segregated schools, he said. Even housing, both on and off post, was often segregated, overtly or otherwise.

"The wives took the brunt of it," he said.

He recounted stories of Soldiers traveling between distant posts in the South who didn't have access to hotels and motels and other places people take for granted today.

Considering the cultural bias at the time, Butler asked Soldiers why they chose to serve.

Most, he said, served out of a sense of duty and patriotism. Some wanted a sense of adventure, a way to get out of the ghettos or rural areas and see the bigger world. Others needed a job or an occupation, and still others wanted an education.

While equality has improved since Vietnam, there are still gaps, Hampton said.

One of the best paths to promotions, Hampton said, is through a career in combat arms. Yet black officers today gravitate to administration, logistics and other supporting career fields.

Part of the reason, Hampton said, is that blacks still see duty in supporting fields as being less subjective. For example, an infantry leader might be rated on intangible concepts like judgment and ability to inspire, while someone at the motor pool might have more objective ratings like vehicle readiness status.

Hampton also thinks black Soldiers look at jobs that translate better to civilian careers, a sort of back-up plan.

"Talking about race can make people feel uncomfortable," he acknowledged.

But having that conversation is important, he emphasized.

While civil rights legislation enacted during the Vietnam era paved the way to greater equality, the struggle is not yet over, he said.

He concluded with a favorite quote spoken by Thurgood Marshall in 1992 -- the first African-American justice on the Supreme Court:

"I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories. We must dissent from the indifference. We must dissent from the apathy. We must dissent from the fear, the hatred and the mistrust ... we must dissent because America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better."

EDITOR'S NOTE: In 2013 Hampton published a book which provides more information on this topic: "The Black Officer Corps: A History of Black Military Advancement from Integration Through Vietnam."

(For more ARNEWS stories, visit http://www.army.mil/ARNEWS, or Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArmyNewsService)

Related Links:

Army.mil: African Americans in the U.S. Army

STAND-TO!: African American/Black History Month: "Civil Rights in America"

Social Sharing