The planning process, beginning with Army design methodology and continuing with the military decisionmaking process, helps the planner prepare to create the operation order (OPORD). Once the staff produces an order, it must be rehearsed and assessed. In this article, we will discuss the orders production, rehearsal, and assessment processes.

The doctrine describing the OPORD format is most applicable to corps-level orders production. This causes a bit of consternation for the sustainment planner. For sustainment commands, battalion and higher, Paragraph 4 (Sustainment) and Annex F (Sustainment) of the OPORD or operation plan describe the internal concept of support. Paragraph 3 (Execution) and Annex C (Operations) detail support operations and elaborate on the supported unit's internal concept of support.

ORDER PRODUCTION RESPONSIBILITIES

Order production is the responsibility of the J/G/S-3 (operations) section. This section compiles the components of the order and issues it to subordinate units. It also creates the portions of the order that deal with missions of higher and adjacent units, subordinate units' tasks, coordinating instructions, command information, and control information (the main body of the order). The operations section is also responsible for the parts of the order that cover decision support products, rules of engagement (Annex C [Operations]), protection (Annex E), civil affairs operations (Annex K), and information collection (Annex L).

The theater sustainment command has a G-5 (plans) section. This section facilitates planning, but the responsibility for issuing the order still rests with the J/G/S-3. The G-5 facilitates the development of draft plans that can be rapidly converted into orders. It also writes Appendix 1 (Design Products) of Annex C and, as the lead of the plans cell, helps develop plans for branches and sequels.

The support operations division is responsible for developing the concept of operations.

The J/G/S-4 (logistics), with assistance from the J/G/S-1 (personnel), the staff judge advocate, the chaplain, and the finance officer, prepare Paragraph 4 of the main body of the operation order, Annex F, and Annex P (Host Nation Support).

The staff engineer position, which varies in section depending on the echelon, is responsible for Annex G (Engineering) and engineering subjects in the main body of the order and Annex F.

OPORD FORMAT

In the main body, Paragraph 1.e. (Missions of Adjacent Units), follows the prescribed format. Include customers and suppliers who are not in your chain of command. Then, relist customers and suppliers and describe their concept of support in Annex C, Paragraph 1.d. (Friendly Forces).

The expeditionary sustainment command recounts the concept of support from strategic partners and division-equivalent organizations. Sustainment brigades describe customer brigade support battalion, or equivalent, concepts of support. Brigade support battalions specify support concepts of the battalions they support by phase. Details include locations, Department of Defense activity address codes, and geographic routing identifier codes.

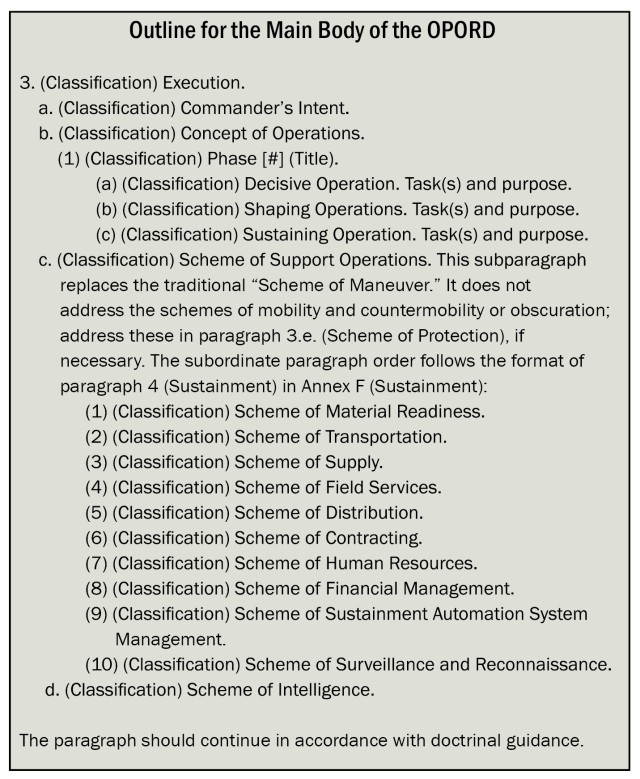

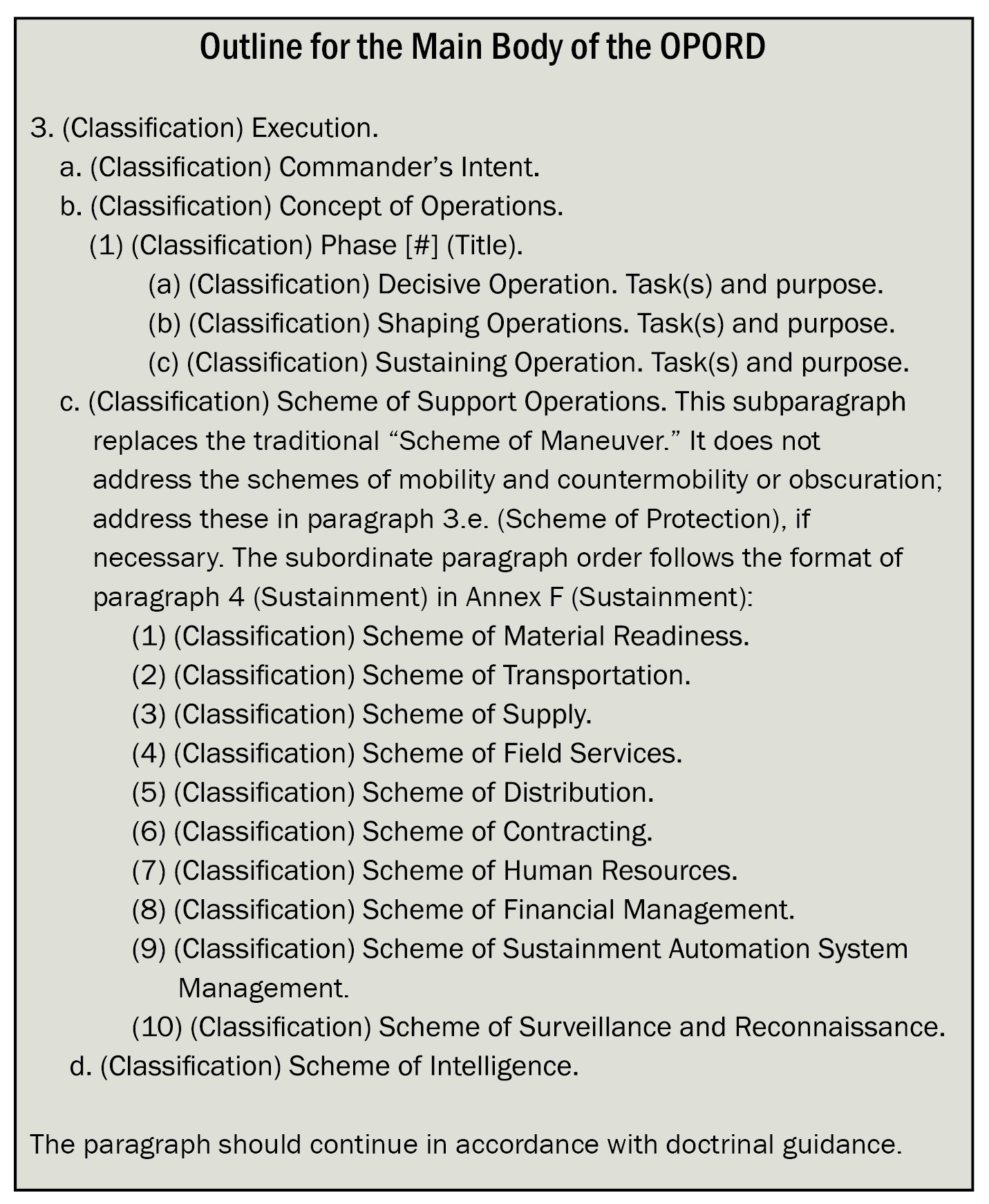

The format of Paragraph 3.b. (Concept of Operations) and Annex C must differ from Army Tactics Techniques and Procedures (ATTP) 5-0.1, Commander and Staff Officer Guide, in order to present the information required to describe support operations and meet the intent of the doctrine. This variance does not take away from, but adds to, prescribed formatting. See figure 1 for our recommended format for the main body of the OPORD.

A technique to limit the number of pages in the main body is to provide a simple paragraph narrative for Paragraph 3.c. The narrative should focus on major hubs, routes, priority of effort, and priority of support for support operations. In this case, include the "Scheme of Mobility" subparagraph and an overview of distribution operations. Also include the "Scheme of Information Collection."

Detail information in Paragraph 3.a. (Scheme of Movement and Maneuver) of Annex C. Rename it "Scheme of Support Operations" and follow the subparagraph format listed above, but this time omit "Scheme of Information Collection."

CONSIDERATIONS FOR ANNEXES

In Annex A (Task Organization), consider including contractors, customers, and suppliers as appendices. Include location, contact information, and identifiers (such as Department of Defense activity address codes and geographic routing identifier codes).

In Annex B (Intelligence), focus on information most pertinent to a sustainer.

In Annex C, include the support operations overlay. Use multiple overlays as needed to clearly depict support operations. Include supplier and customer graphics as much as possible. Always include the support operations synchronization matrix and decision support tools. Omit the appendices that do not apply to the situation. If gap crossing, air assault, airborne, amphibious, or special operations apply, address the support operations plan for each operation in detail.

Annex D (Fires) can typically be omitted when information about fire support is covered in the main body of the OPORD.

Annex E (Protection) refers to internal operations but should discuss coordination with outside agencies (such as the base defense operations center) as required. Reference other documents, such as the personnel recovery plan dictated by the maneuver unit that controls the area of operation, rather than repeating it. Ensure that the referenced document is available to subordinate units. Appendices usually will not be required.

Annex F (Sustainment) follows the doctrinal format. This annex applies to internal operations. Use appendices, tabs, and enclosures as required, but avoid detailing standard operating procedure information. Also, reference higher headquarters' guidance, such as legal and financial management information, rather than repeating it.

Annex G (Engineering) should be omitted if Annex B and Annex F cover required engineering subjects.

Annex H (Signal) references internal signal operations. Address sustainment automation systems management in the main body of the order and Annex C.

Use Annex J (Inform and Influence Activities) only when necessary. Typically, all required information is available in the main body of the OPORD under "Themes" in the "Coordinating Instructions" subparagraph of Paragraph 3.

Annex K (Civil Affairs Operations) may require a lot of detail if the sustainment unit is a primary supplier of class X (materials for nonmilitary programs). If not, consider discussing any details in Paragraph 1.f. (Civil Considerations) of the main body of the OPORD or Annex C and omit this annex.

Annex L (Information Collection) may be omitted because sustainment personnel do not normally have the training and resources to conduct reconnaissance and surveillance. If the unit does have designated information collection tasks, then include the annex.

Annex M (Assessment) is critical to the process. We will discuss assessment in detail later.

Annex P (Host Nation Support) and Annex V (Interagency Coordination) address different topics but are similar in that they deal with organizations with which the sustainer must coordinate. In a sustainment OPORD, Annex P addresses host nation contracting on a large scale. Similarly, Annex V details coordination with sustainment partners but has only an overview of other agencies operating in the area.

In Annex R (Reports), use the appendices to detail the battle rhythm, report formats not found in Field Manual 6-99.2, U.S. Army Report and Message Formats, and board and meeting agendas (sometimes referred to as "7-minute drills").

Annex S (Special Technical Operations) and Annex U (Inspector General) are for echelons above brigade; omit them. Occasionally higher orders may contain pertinent information in these annexes. If so, incorporate that information into "Coordinating Instructions."

REHEARSALS

Sustainment is a highly complex operation. Without a rehearsal, the sustainment commander is standing on blind luck and the ingenuity of his subordinates to accomplish the mission. As sustainers, we have to ask a great deal from our subordinates. Let us not do them the disservice of failing to rehearse.

The military decisionmaking process step of the course of action analysis provides for wargaming. ATTP 5-0.1 defines wargaming as an "attempt to visualize the flow of the operation." Wargaming is the first rehearsal that a unit conducts. The object is to coordinate and synchronize events and identify enemy and civilian impacts on operations.

Following the issue of an order, the sustainment unit should conduct an internal rehearsal with subordinate elements at least two levels below. This rehearsal verifies the subordinate units' understanding of the order and timing required. It provides a great deal of assistance in supporting the planning effort and clarifies required coordination.

As with planning, the sustainment commander and staff must consider the advantages and disadvantages of integrating directly into the maneuver customer's rehearsal schedule, conducting a completely separate rehearsal, or doing both. In a time-constrained environment, the integrated rehearsal is best. In a high operating tempo operation, conducting two rehearsals (integrated and sustainer specific) is best.

FORMAL REHEARSAL

Some rehearsals are more important than others. During an upsurge of forces or a theater closing, sustainment operations become the decisive operations. In such cases, senior commanders (division level and above) become very interested and request rehearsals of concept in order to ensure coordinated, synchronized, and effective execution of the operation.

To execute a formal rehearsal, allow appropriate time. Subordinate units must have time to prepare their portions of the operation. The executing command must plan on conducting collaboration meetings and at least three prerehearsals. Subordinate units must submit products on time, and the executing command must complete the quality review before the rehearsal and effectively manage versions of the briefing.

There are important points to consider for effective presentation. The executing commander establishes certain themes that each participant addresses throughout the rehearsal. During collaboration meetings and prerehearsals, the participants develop "linkages" among presenters, reduce friction points, and eliminate conflicting information.

The executing command nests its themes into higher headquarters plans and includes adjacent units (suppliers and customers) in the rehearsal. Mastery of material and confidence in presentation lead the recipients of the rehearsal to trust the participants to be able to execute as presented. Use of a common font, color scheme, and backgrounds in the presentation material makes the presentation easier to digest.

Preparations include the briefing area and administrative requirements. Briefing area preparations include the sand table (or equivalent), wall maps, graphics, unit icons, seating, sound, projector, videography, and telephones. Administrative preparations include security (facility, gates, doors, and transportation), parking, refreshments, location, clean-up, drivers and transportation, billeting, meals, and protocol (VIP guest list and invitations, escorts, social, formal dinner, flags, placards, and special instructions).

As a final note, think of rehearsal as the alter ego of wargaming. The more thorough the unit conducts the course of action wargaming, the smoother the rehearsal. If wargaming is conducted quickly or merely as a "check the block" action, the quicker the rehearsal will degenerate and ultimately desynchronize the OPORD or operation plan.

SUSTAINMENT ASSESSMENT

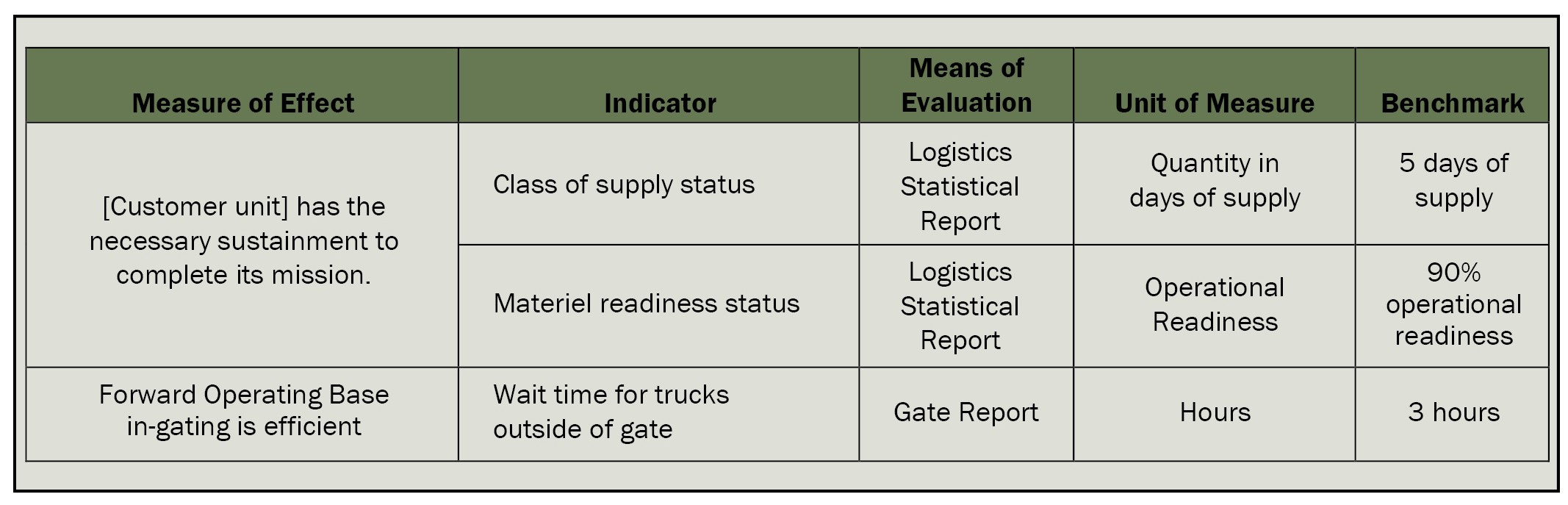

Failure to assess is tantamount to planning to fail. Assessments begin with indentifying tasks. Through analysis of the tasks required of a unit and the commander's desired end state, the sustainment planner determines measures of effectiveness (MOEs) and associated indicators. An MOE states a measurable condition; the civilian equivalent of the term is "metrics." Indicators provide the observable means for measuring the MOE. These indicators are very similar to the evaluation criteria described in ATTP 5-0.1.

Using inspiration from the information collection matrix, we have added a "Means of Evaluation" column to the indicator description to identify the collection method. (See figure 2.) MOEs and indicators identified during mission analysis become the evaluation criteria used during course of action analysis and continue throughout mission execution.

Sustainment planners derive MOEs directly from task requirements deduced during mission analysis. Tactical and hazardous risks originate in factors that may lead to the failure to meet an MOE. These factors have a negative effect on the systems that contribute to success. This link between MOE and risk focuses protection efforts of critical asset identification, vulnerability analysis, and protection (or mitigation) efforts.

Sustainers use assessment continuously. Current operations assess mission progress. Support operations branches assess the statuses of the tasks within their functional areas. At times, leaders find it difficult or inconvenient to define "right" or how to measure it. There are many excuses available to crawl into such a rut, but none are valid. Sustainers must define their tasks and the means by which to measure progress and success. This is logistics analysis.

High quality logisticians conduct analysis and assessment so that their commanders have a thorough understanding of their operational environment and what decisions are required. Sustainers conduct logistics analysis and assessment in such detail that the supported commander is never caught unaware with a critical shortage or failure of systems. Sustainers deal daily with a data deluge.

As a rule, sustainers are adept at using charts and graphs to mold data into information. Comparing the information to assessment criteria provides the sustainer with the knowledge needed to provide the sustainment commander with situational understanding. Comparing information to assessment criteria also provides sustainers with evidence of a variance from the anticipated flow of events and alerts them to the possibility of the need for a branch, sequel, or full revision of the plan. The standardized tool to conduct assessment and analysis is the running estimate. (See part 2 of this series in the May-June 2013 issue of Army Sustainment for a discussion of the running estimate.)

Sustainment planning, rehearsal, and assessment conform to doctrine. As with all functional areas, sustainers should feel free to modify formats to fit their specific needs. Doctrine provides a standard process, but planners must still effectively analyze and plan for their individual situations. Doctrine works. It is time proven, but it is also flexible--a foundation and framework, not a prison.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. John M. Menter is a retired Army colonel and a doctrinal training team lead for Doctrine Training Team #11 based out of the Mission Training Complex at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pa., as part of the Mission Command Training Support Program, Team Northrop-Grumman/CACI, Inc. He holds a doctoral degree in history and an MBA degree from the University of La Verne. He is a Certified Professional Logistician.

Benjamin A. Terrell is a lieutenant colonel in the Alabama Army National Guard and serves as the intelligence and sustainment subject matter expert on Doctrine Training Team #11 based out of the Mission Training Complex at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pa., as part of the Mission Command Training Support Program, Team Northrop-Grumman/CACI, Inc. He holds a bachelor's degree in social studies from Southeastern Louisiana University and a master of divinity degree from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the July-September 2013 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Browse Army Sustainment Magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Army Sustainment Magazine News

Social Sharing