During an Operation Enduring Freedom deployment, a planner with the J-5 shop of an expeditionary sustainment command heard a commander say, "I'm tired of hearing what doctrine says; I want something that works." This attitude is exhibited by many commanders and staffs. They will try the latest fad or creative method to create doctrine-like tactics, techniques, and procedures. Then when all else fails, they try the doctrinal method and find that doctrine worked best. In fact, maybe the conflict in Afghanistan should be labeled "The Post-Modern War Experiment." Doctrine is the foundation from which the Army conducts its operations. Yet, doctrine is just a generic template to modify the current situation.

The planning process, as found in Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 5-0, The Operations Process, and Army Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures 5-0.1, Commander and Staff Guide, is doctrine. Each warfighting functional area modifies the format of the products that make up the plan to fit its unique requirements. The sustainment warfighting function is no different.

This is the first of a series of three articles that reviews the planning process, from Army design methodology through assessment, and discusses the modifications and distinctive variations sustainment planners can apply.

Since its introduction in May 2010, the Army design methodology has received more than its share of attention. For the most part, Army design methodology is misunderstood by many and overcomplicated in application. Some believe that design should replace the military decisionmaking process (MDMP) in certain situations or that design applies in only certain situations. Hard-liners on the far right just turn their backs and return to the seven MDMP steps. In some cases, sustainers use neither Army design methodology nor the MDMP; they just put their main logistics hub and satellite hubs where they are told and then focus on consolidating requests and distributing supplies and services as rapidly as possible. For sustainers who say, "Why should I plan? There is really only one course of action," Army design methodology is for you.

WHAT IS ARMY DESIGN METHODOLOGY?

The purpose of Army design methodology is to help the commander (or planner) define the "what" of planning, understand the problem, anticipate change, create opportunities, and recognize and manage transitions. Army design methodology has four "frames" (or steps): understand the current operational environment, define the desired operational environment, define the problem, and develop the operational approach. The process results in four major products: the problem statement, the commander's initial intent, the commander's initial planning guidance, and the mission narrative.

Understanding the current operational environment is basically the same thing as a good intelligence preparation of the battlefield. It focuses on tactical and operational variables to answer the following questions:

• What is occurring in the area of operations?

• Who are the main actors?

• Where are actions that could affect the success of the mission (both positively and negatively) occurring?

• Why are those actions occurring where they are occurring under the supervision of particular leaders?

Understanding the operational environment attempts to dig deeper than the surface layer of leaders, locations, events, and causes in order to discover the centers of gravity that actually drive the people and events in the area of operations.

It is the commander's responsibility to define the desired operational environment, or end state. This begins with a thorough understanding of the commander's intent two levels higher, which requires an in-depth understanding of the next higher level commander's intent. It also requires the flexibility of the next level higher commander to allow his subordinates to modify assigned tasks in lieu of following detailed instructions. Recognizing the difference between the current operational environment and the desired operational environment leads to identifying the problem and developing the operational approach.

Defining the problem is the method the commander uses to focus the efforts of the staff. The operational approach provides the staff with the lines of effort and major tasks required to shape the desired operational environment. With the problem statement as a foundation and the operational approach as an outline, the commander develops his intent and guidance.

The mission narrative is a variation of the commander's intent that forms the foundation for themes. It is the commander's vision of the operation as he would like to present it publicly. It is what he wants those observing his actions to understand and expect from the operation.

DESIGN IN THE HANDS OF SUSTAINERS

Many writers emphasize that Army design methodology is for complex and ill-structured problems. Sustainers live in a complex, ill-structured environment. Trying to follow orders from both the higher headquarters and supported headquarters does not always leave the sustainment commander with many options. Army design methodology provides the sustainment planner with both an opportunity to analyze the mission from unique angles and an operational approach that focuses on addressing sustainment task effectiveness and efficiency.

Army design methodology allows the sustainment planner to analyze the mission from the perspective of a sustainer's operational environment. It allows the planner to ask, "What is my world like relative to the operational variables?" and "How do I want my world to look?"

Too often, the sustainer focuses solely on the enemy while developing the intelligence preparation of the battlefield. Yet of all the operational variables, the enemy often has the least significant impact on the sustainer's mission. Time is the sustainer's greatest enemy. Terrain, economy, and infrastructure have huge impacts on how quickly the sustainer performs his mission effectively and efficiently.

PLANNING MATRICES

Planners can use matrices to assist them in their decisionmaking. Matrices can address a number of subjects, including the operational variables and functions, operational variables and locations, a comparison of functional areas with the current situation and the desired situation, and lines of effort details.

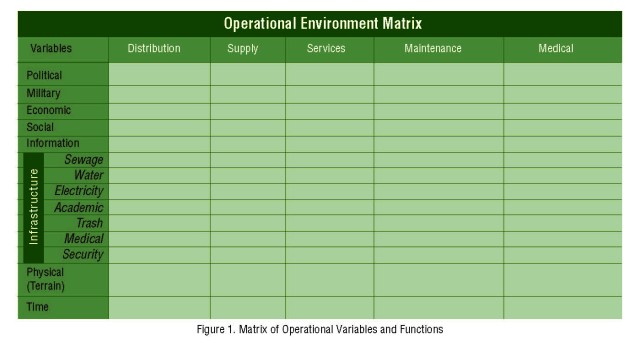

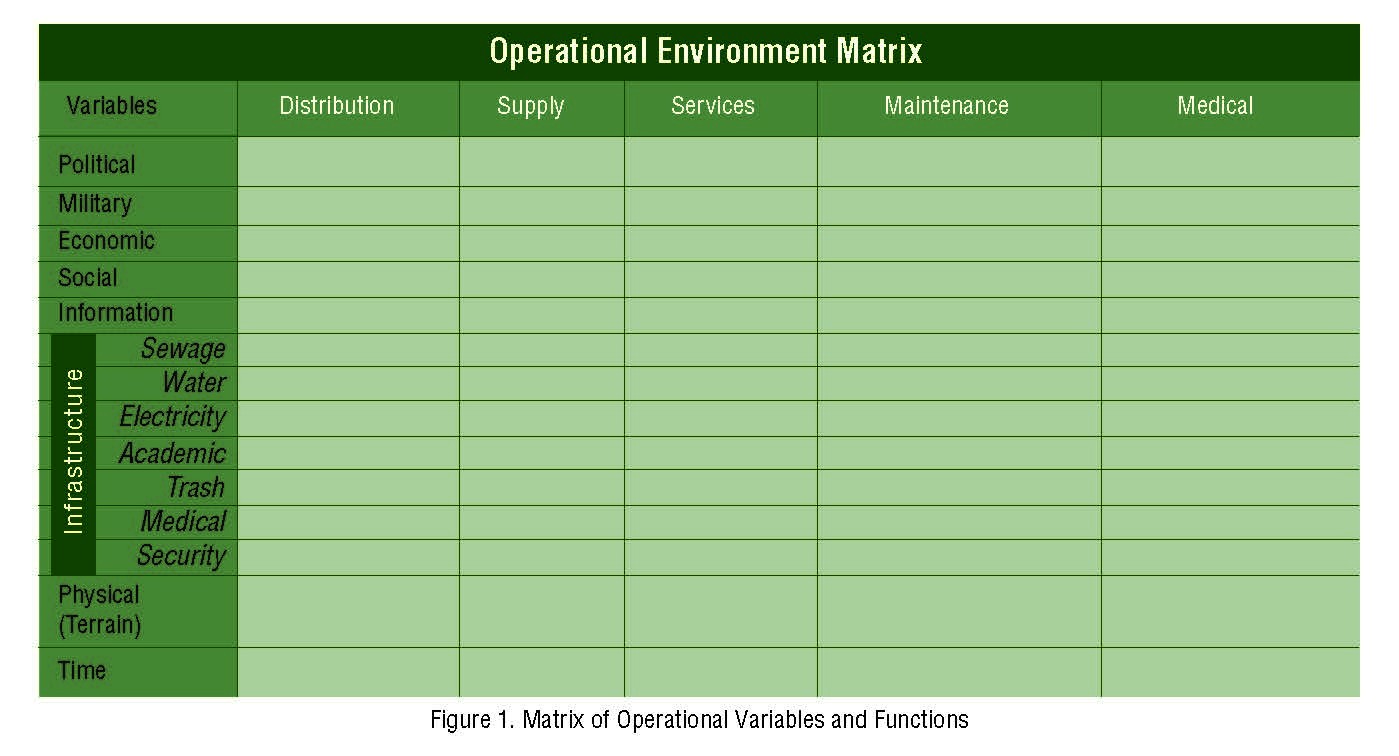

Figure 1 illustrates a matrix that addresses the operational variables and functions. In this chart, functional areas are used as the header; the commander or support operations officer chooses which functional areas to focus on. Rather than using functional areas, the sustainment planner may opt to focus on locations or customers. Although the chart would look the same, the header would reflect the commander's emphasis: functions, locations, or customers.

Army design methodology also allows the sustainment planner to define the end state relative to the unit's functions or operational locations. The sustainment planner may weigh the critical functions against the operational variables to understand the current operational environment and define the desired end state.

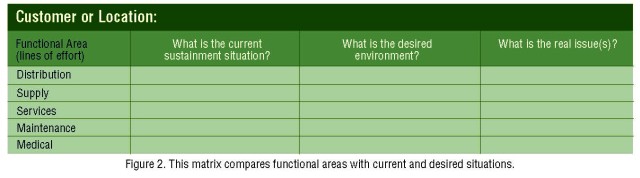

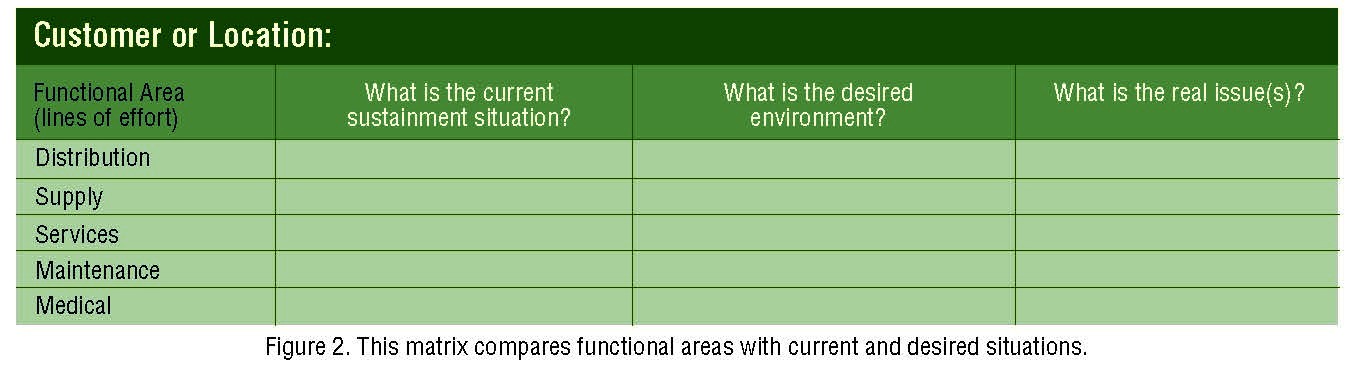

Figure 2 provides an example of a matrix the sustainment planner can use to detail this information. This allows the planner to easily compare the current situation with the desired environment. From this analysis, the planner identifies the problems associated with each functional area, location, or customer.

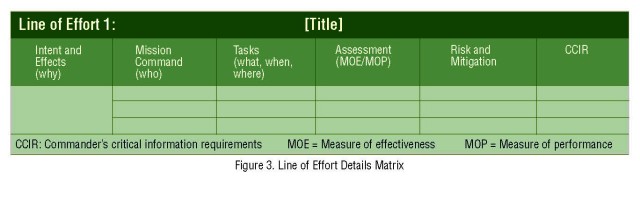

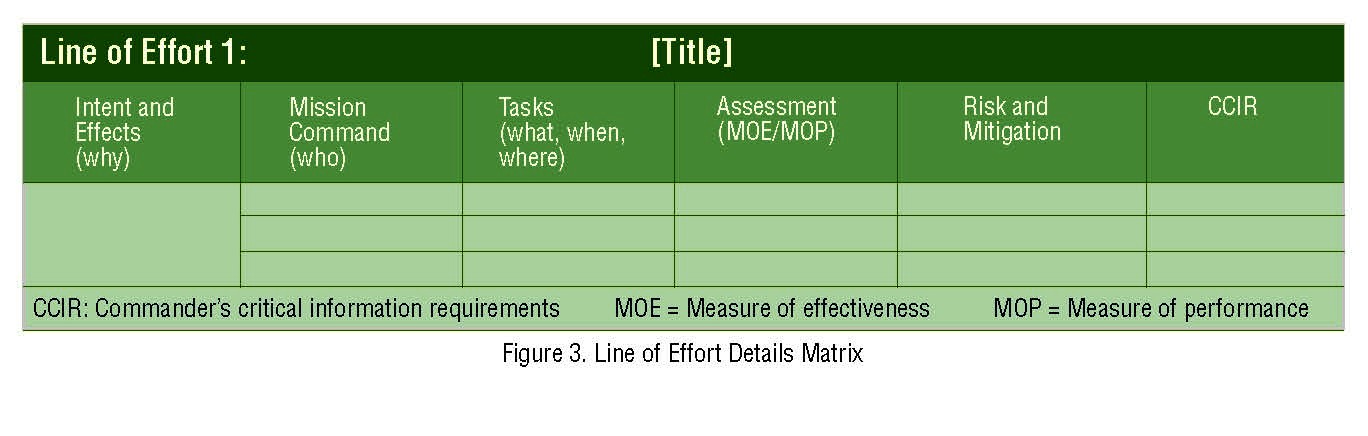

The planner must look past the surface issues and identify the deeper problems that hamper effective and efficient sustainment in the area of operations. Identifying these key issues or problems will indicate the lines of effort that the command must address to accomplish the commander's intent. With lines of effort, the sustainment planner articulates a desired intent (why), key tasks (what, when, and where), assessment criteria (measure of effectiveness), tactical risk (and corresponding mitigation), and the commander's critical information requirements. See figure 3. This action is very similar to developing a course of action. By focusing thought on one problem or line of effort at a time, it is much easier for the sustainer to detail assessment criteria, risk, and critical information requirements.

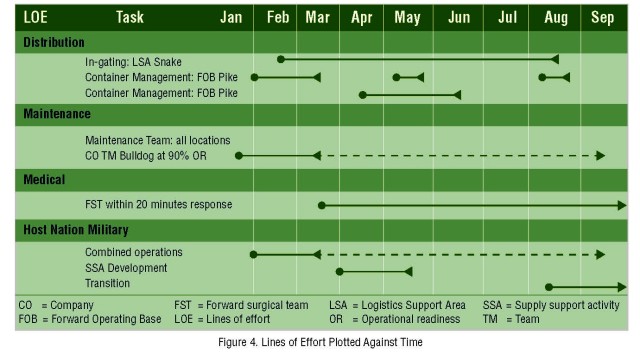

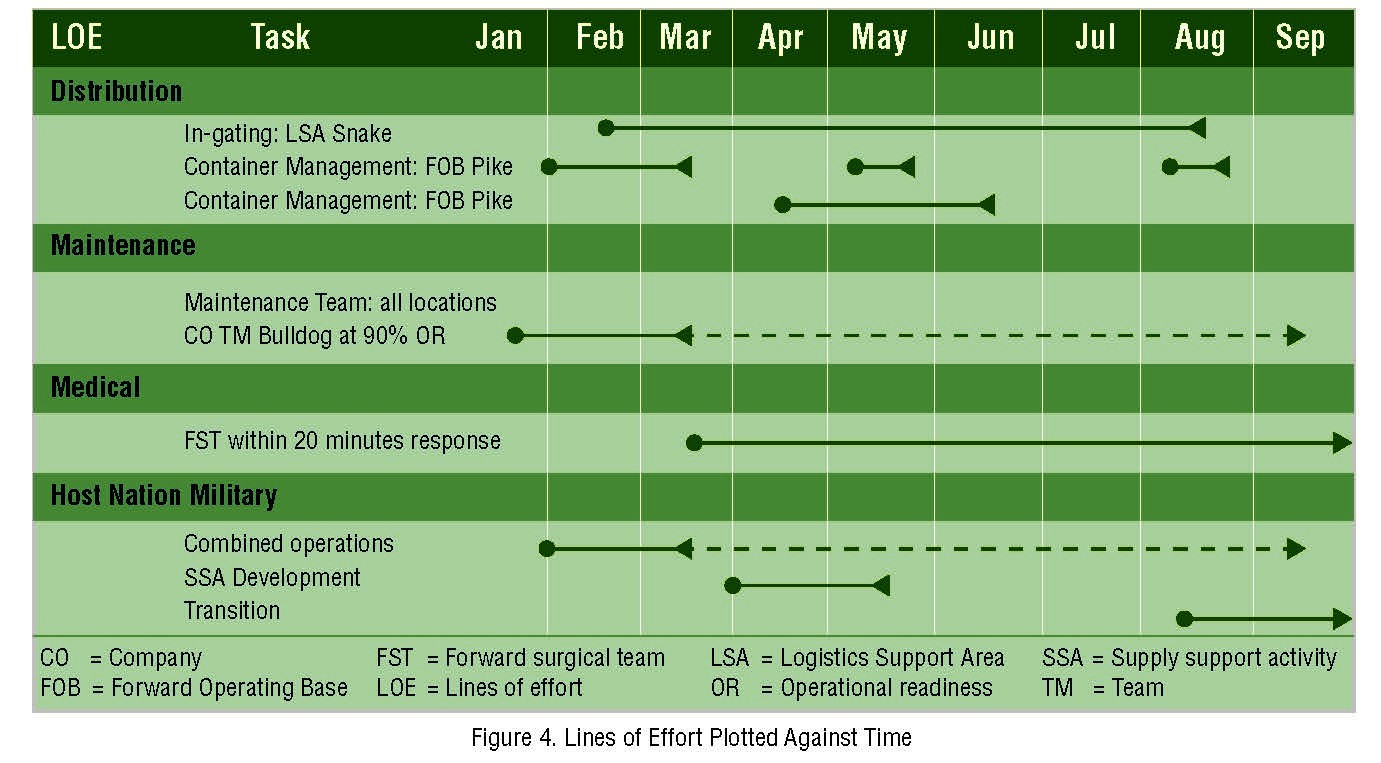

When applying time to the combined list of lines of effort, the sustainment planner can easily identify where resources need to be and when they need to be there in order to most effectively address all issues. This matrix also aids in the development of a logistics synchronization matrix. Figure 4 illustrates lines of effort based on functional areas with tasks concentrating on locations or customers. One can easily change the lines of effort to locations with tasks addressing functional requirements.

Although the timeline in the chart illustrates nine months, a good operational approach extends from preparation for operations through consolidation and reorganization to the follow-on operation, phase, or sequel. If it extends beyond the unit's deployment cycle, it forms the basis of mission analysis for the follow-on unit by illustrating the preceding commander's intent, actions accomplished, and an assessment of progress.

MEASURING EFFECTIVENESS

The focus of the operational approach allows the sustainment planner to identify measures of effectiveness and measures of performance for each critical task identified in the plan. This facilitates assessment throughout the execution and provides the chief of operations with an effective means of determining when he should initiate a sequel or branch or call a planning meeting to re-address the method required to accomplish the task.

Measures of effectiveness and performance provide indicators. Indicators lead to decision points. Decision points require a commander's critical information requirement. Once the intelligence and operations officers identify a method to monitor a decision point that answers the commander's critical information requirement, the unit has a reconnaissance and surveillance plan and an assessment plan. The sustainment planner should incorporate the decision points into the lines of effort matrix.

REFRAMING

Army design methodology uses a technique called "reframing" to describe set points in which the staff conducts an assessment and decides if the problem they are addressing is the actual problem and if they are using the correct methods. Reframing may occur at set intervals (for example, the battle update assessment every Saturday) or just prior to or following a particular event or action (during the transition between phases).

Reframing helps keep the unit's actions focused on the true problem. Without that focus, tasks become monotonous and attitudes lackadaisical. Reframing asks, "Are we doing the right things?" and "Are we doing the right things correctly?"

Like all aspects of Army design methodology, the commander does not accept the surface answer but digs into the second and third order of effects. The sustainment brigade commander does not settle for the answer from the combat sustainment support battalion commander or even the quartermaster company commander. He asks the supply support activity manager if he believes his activity is running in its most effective and efficient manner. The combat sustainment support battalion commander solicits input from the supply support activity's workers, contractors, and customers.

Army design methodology is a critical component of the Army operations process. It is a tool designed to help commanders accurately understand the operational environment, visualize the desired end state, describe their intent, direct the focus of the operations to key tasks and concerns, and assess progress for branches and variances. Therefore, it is a key component in achieving mission command. It is also a tool sustainers can use to approach mission analysis from a more refined degree of inspection.

Army design methodology does not replace the MDMP, although it does mirror mission analysis and course of action development. The MDMP is the keystone of the Army operations process and requires the sustainer to approach it from a unique perspective to provide the best products for the sustainment commander and the supported commanders.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. John M. Menter is a retired Army colonel and a doctrinal training team lead for Doctrine Training Team #11 based out of the Mission Training Complex at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pa., as part of the Mission Command Training Support Program, Team Northrop-Grumman/CACI, Inc. Over the past 10 years, he has conducted hundreds of military decisionmaking process training seminars. He holds a doctoral degree in history and an M.B.A. degree from the University of La Verne. He is a Certified Professional Logistician and is the author of "The Sustainment Battle Staff & Military Decision Making Process (MDMP) Guide: For Brigade Support Battalions, Sustainment Brigades, and Combat Sustainment Support Battalions (Version 2.0)."

Benjamin A. Terrell is a lieutenant colonel in the Alabama Army National Guard and serves as the intelligence and sustainment subject matter expert on Doctrine Training Team #11 based out of the Mission Training Complex at Fort Indiantown Gap, Pa., as part of the Mission Command Training Support Program, Team Northrop-Grumman/CACI, Inc. He holds a bachelor's degree in social studies from Southeastern Louisiana University and a master of divinity degree from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. He is a graduate of the Military Police Officer Basic Course, the Engineer Officer Advanced Course, the Combined Arms and Services Staff School, the Senior Transportation Officer Qualification Course, and the Support Operations Officer Course.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the March-April 2013 issue of Army Sustainment Magazine.

Related Links:

Browse Army Sustainment Magazine

Social Sharing