ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, Md. -- It looks like anthrax. It resembles most of the physical properties of the Bacillus anthracis bacteria. It even has a genetic make-up similar to that of the deadly pathogen, and most importantly, it makes hardy, durable spores like its virulent cousin. But it's not anthrax. It is an imposter used as a simulant in a groundbreaking effort at the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center to improve emergency preparedness in the event of a biological attack.

The simulant, Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki, is safe. It's found in nature and available to the public at garden supply stores as a gypsy moth caterpillar control agent in organic farming.

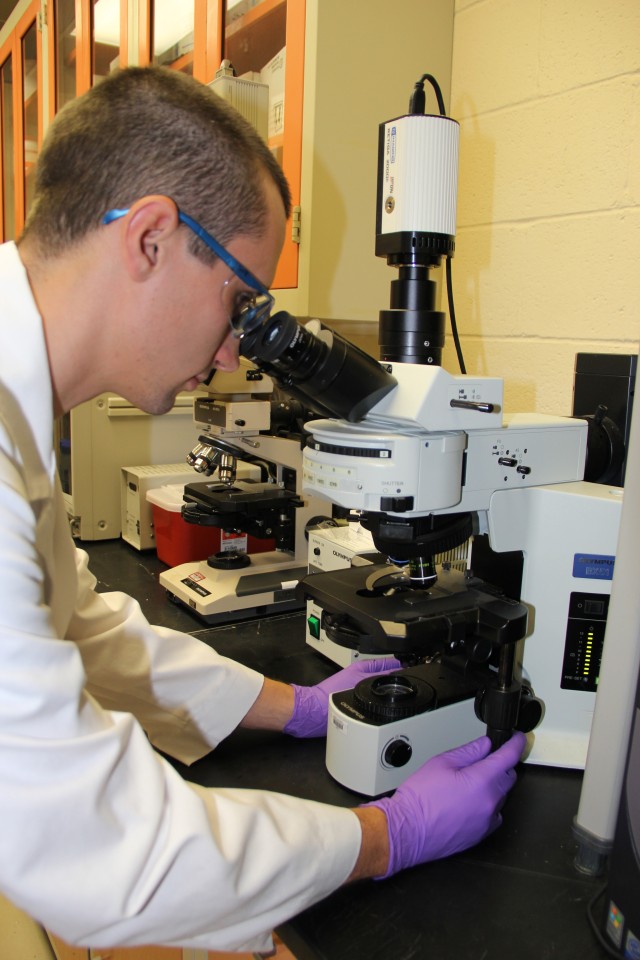

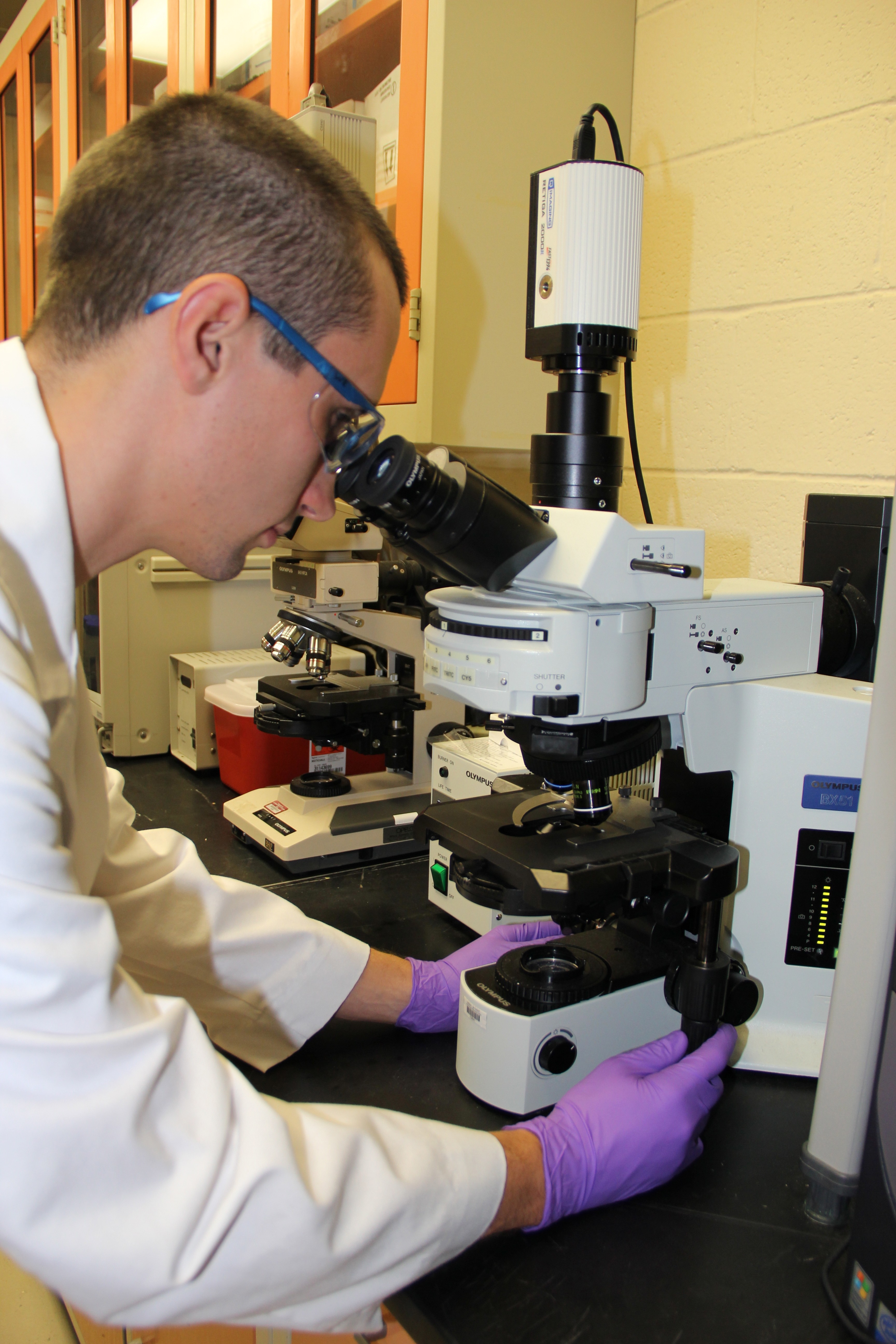

For Dr. Henry S. Gibbons, an ECBC research microbiologist, it is the cornerstone of his group's work with a barcoded spore technology that uses small genetic signatures to track and identify the simulant spores during large-scale outdoor testing.

Monitoring the transportation patterns of simulant strains that mimic the behavior of actual anthrax spores increases the quality of data gathered by researchers, which could eventually be used to help mitigate the costs of clean-up and the extent of social disruption in the event of a real world biological attack.

"The barcoded spore technology helps us prepare for the eventuality of an attack," Gibbons said. "If we get hit again with something, we will have a better sense of where to clean it up, where it is likely to go, where to focus our emergency response efforts and determine what areas are at greatest risk."

Each genetic signature, or barcode, contains common and specific tags that are integrated into neutral regions of the DNA of the simulant Btk for tracking. ECBC researchers are able to detect and discriminate the barcoded strains from wild-type strains as well as from each other, which enables large-scale testing that could sample more than a dozen pieces of information and dramatically optimize data gathering.

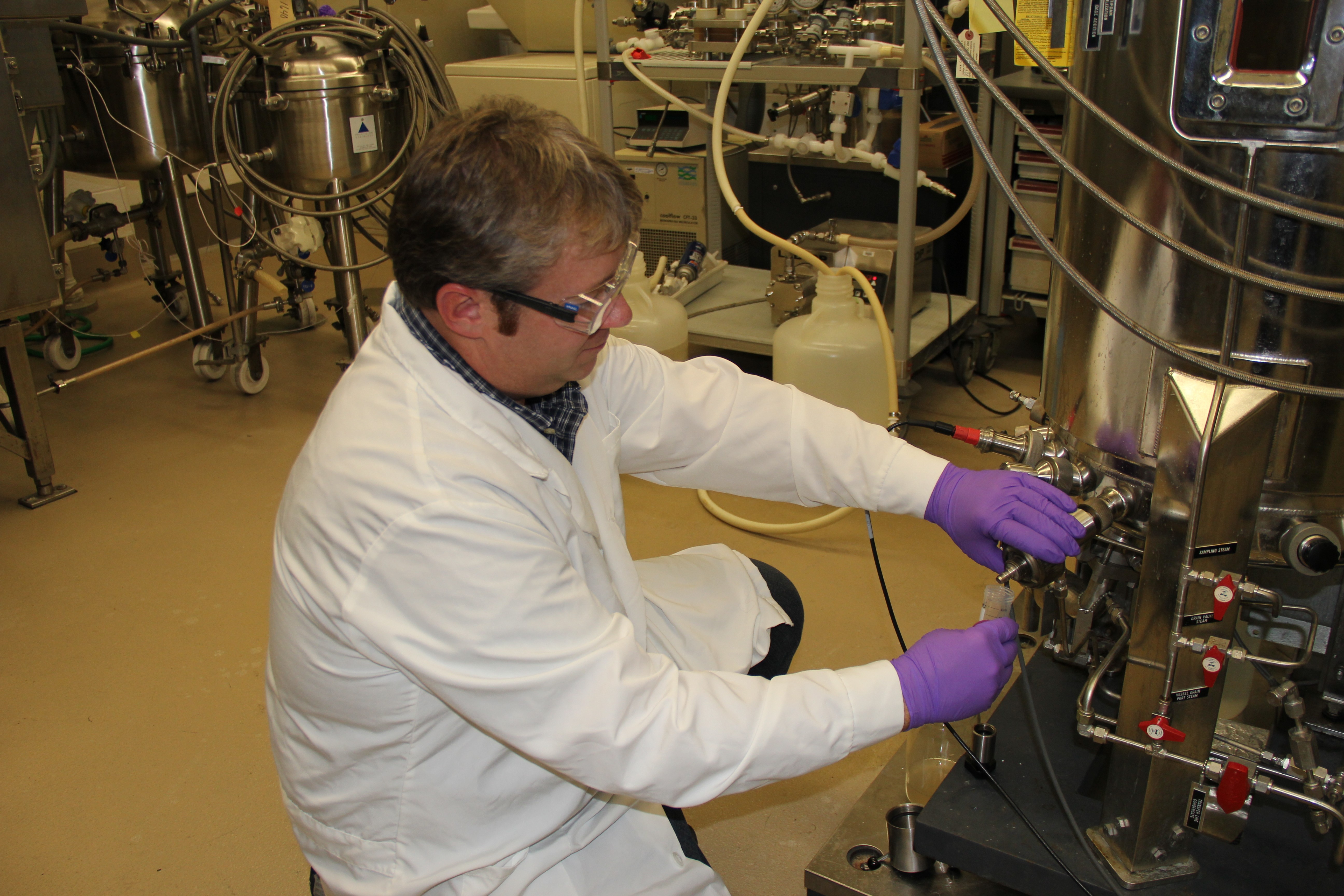

Previous data gathering methods used by ECBC were expensive, labor intensive and involved more than 50 people to set up the outdoor detectors, which collected a limited amount of information in a single test. According to Gibbons, the barcoded spore technology simplifies collection efforts, reduces testing costs and improves the control of previous uncontrollable variables that affect how bacterial spores behave when discharged in an open environment. Large-scale testing now gives researchers the opportunity to trace the simulant in more populous locations such as city subways or residential suburbs.

ECBC selected the simulant Btk strains used in the barcoded spore testing because of the center's commitment to safely conducting projects in an environmentally sound manner. The simulant is an ingredient registered with the federal Environmental Protection Agency and found in common commercial products such as Dipel or Thuricide pest control, which is sold online and across the country at garden supply stores. The kind of large-scale testing in various conditions that Gibbons is striving for is a direct result of the heightened safety measures his team uses on a daily basis, with the EPA-registered Btk strain living at the core of the work.

"Better testing methods under multiple conditions can help improve our predictive models for different potential biothreat scenarios," Gibbons said.

"We're hoping that we have a technology in these barcoded spores that can actually allow some testing on either mock structures or various test beds where people can do some of these modeling studies with an organism that is relatively representative of what they would find in actual virulent Bacillus anthracis."

This new technology could be a tremendous asset to clean-up efforts in the wake of a future biological attack, he said, recalling how swabbing representative areas of various locations during the 2001 anthrax attack was the only effective way to track the pathogen during its outbreak through the U.S. Postal Service more than a decade ago. It marked the country's first case of bioterrorism when contaminated letters were mailed to congressional leaders and members of the news media. Gibbons called the Amerithrax events, as it was classified by the FBI, "one of the major catalysts for the expansion of the biodefense industry as we know it today."

By pursuing large-scale testing in real-world environments, barcoded spores could gather innumerable data that could better predict the behavior of a real biological agent and direct further decontamination efforts in a focused, more effective way.

In 2001, it took hundreds of thousands of hours for the FBI's Amerithrax Task Force, which consisted of nearly 30 full-time investigators from the FBI, The U.S. Postal Inspection Service and several other law enforcement agencies and federal prosecutors, to work on the case. During 80 searches, more than 6,000 items of potential evidence was recovered in addition to 5,730 environmental samples collected from 60 site locations.

The FBI investigation was just one part of the anthrax clean-up, however. The EPA also contributed decontamination efforts, spending about $27 million on the Capitol Hill anthrax clean-up alone, according to a 2003 U.S. General Accounting Office report. The cost was more than five times the $5 million the EPA had originally estimated. While Capitol Hill office buildings were reopened in about 3 months, other contaminated buildings like the Brentwood postal facility in Washington, D.C. remained closed until 2003.

"One of the problems that came out of the aftermath of the anthrax attacks was we didn't have a good sense of where to look for these spores and how to track them. We still don't have a very good sense for how long they'll last in a given environment," Gibbons said. "Anthrax has stunningly long term viability and that's one of the problems of the anthrax clean-up. The current standards for clean is there are no spores in a given location, but how do you certify that? Do you swab every centimeter of every surface?"

October 5 signified the 11th anniversary of the first death related to the anthrax attack when a 63-year-old Florida man passed away from medical conditions caused by the inhalation of the bacteria. It was the first in a series of cases than spanned from Florida to New York, New Jersey and Washington, D.C., and resulted in five deaths and 17 illnesses.

"The inhalation form is quick, it's virulent, and it's hard to treat once you have symptoms. There's a very good chance, despite medical intervention, that you will succumb to it in spite of the best efforts of clinicians and antibiotics. It's just a nasty disease. Fortunately, it's not contagious from person to person," Gibbons said.

According to a September report from Global Business Intelligence Research, the U.S. government has allocated more than $50 billion since 2001 to address the evolving threat of biological weapons, including the research and acquisition of medicines. Emergent BioSolutions, a global biopharmaceutical company that manufactures the anthrax vaccine, was recently reported to increase its production from 7-9 million vaccines to 25 million. These are the trends of a growing biodefense market, but in the social reality of the country, state health departments across the nation are implementing anthrax exposure drills in schools and county facilities as part of disaster preparedness programs.

The work being done by Gibbons and his team furthers emergency response efforts with a barcoded spore technology that expands testing opportunities across research communities. The vast amount of information collected and data gathered could have a monumental impact on how first responders, medical personnel and decontamination teams operate during a potential crisis and future attack.

As a premier center that specializes in solutions to counter chemical biological threats to U.S. forces and the nation, ECBC's best offense is a good defense. In order to prepare for the worst-case scenario, the Center is continuing extensive research and engineering innovative technologies that unite and inform the national defense community.

Social Sharing