Redstone worker Sonnie Hereford IV is a Huntsville civil rights pioneer.

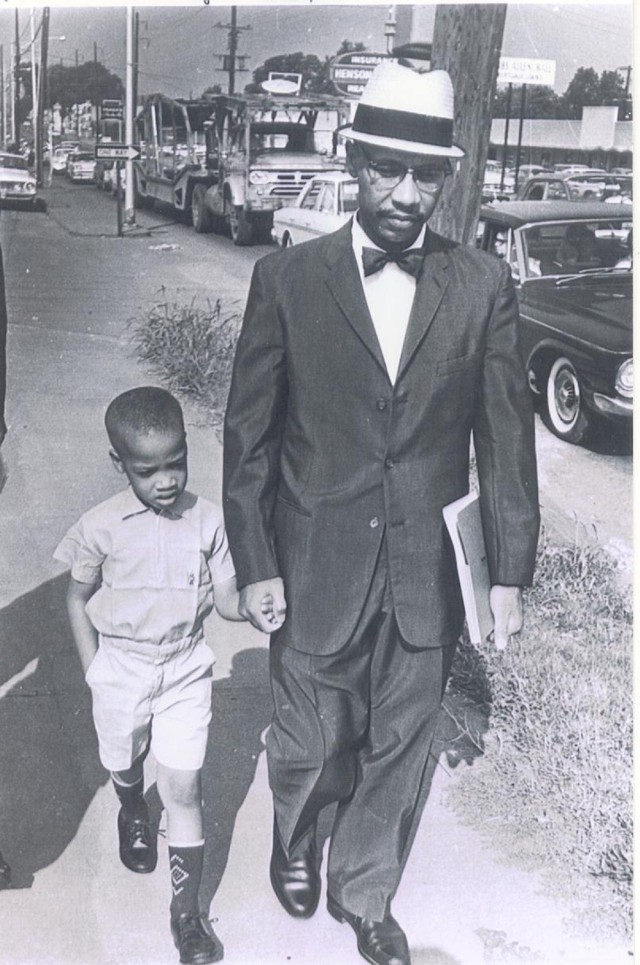

With February’s observance of Black History Month, Hereford shares his memories of being the first Black student in a White school in Alabama in the early 1960s. An iconic photo shows him with his dad on the day they tried to integrate Fifth Avenue School in Huntsville.

He clarified a common misperception about that photo taken Sept. 3, 1963. Generally, people assumed it showed him being escorted to school. Actually they were returning home after being turned away from the Fifth Avenue School. Defying a federal court ruling, Alabama Gov. George Wallace had ordered the Fifth Avenue School and three other schools closed rather than admitting Sonnie and other Black students.

“We’re walking back home east down Governors Drive, not toward the school,” Hereford said.

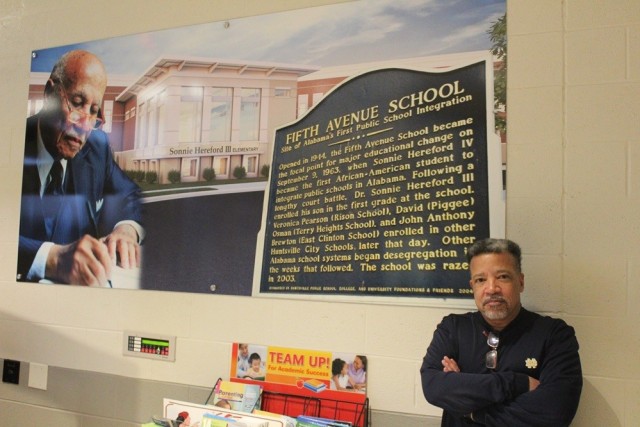

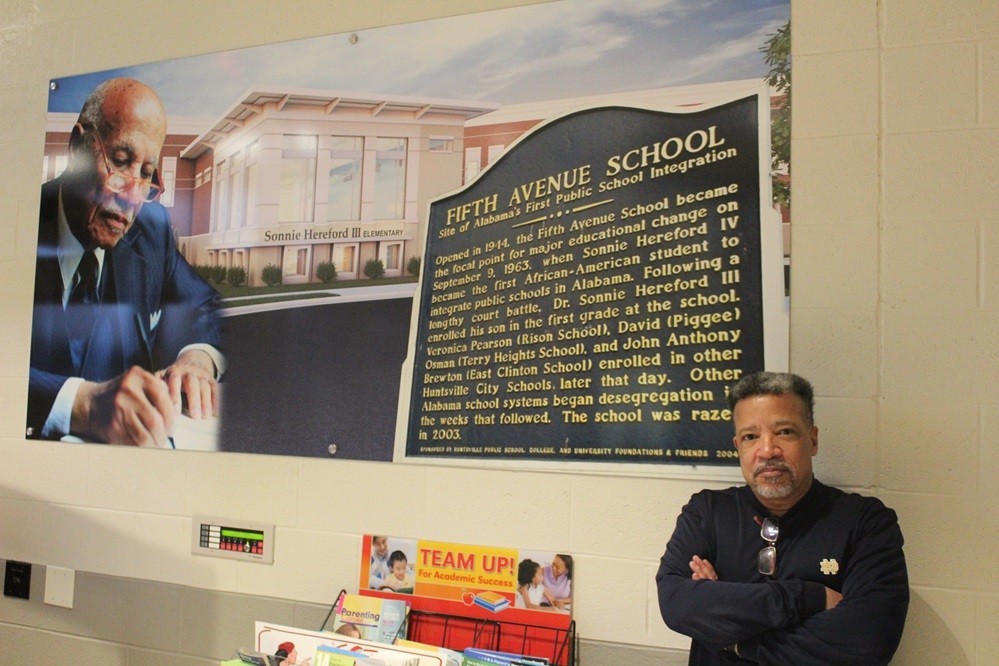

Six days later, on Sept. 9, 1963, his dad, Dr. Sonnie Hereford III, was allowed to enroll 6-year-old Sonnie into first grade at the Fifth Avenue School. They walked hand-in-hand through the schoolhouse door, marking the beginning of integration in public schools in Alabama.

Hereford has many other photographs from that era. This includes March 1962 when Martin Luther King Jr. visited Huntsville and spoke at First Baptist Church and Oakwood College.

“I was only about 4 years old,” Hereford recalled. “When I was 4, not quite 5, I was marching with everybody downtown.”

Dr. Hereford started a lengthy

court battle; and on Aug. 14, 1963, in federal court in Birmingham, Judge H.H. Grooms of the Northern District ruled that the four Black students in Huntsville who were the focus of the lawsuit should be admitted to the traditionally Whites-only schools in the city. He further ruled that he wanted to see a plan by Jan. 2 to desegregate all the schools in both Huntsville and Madison County.

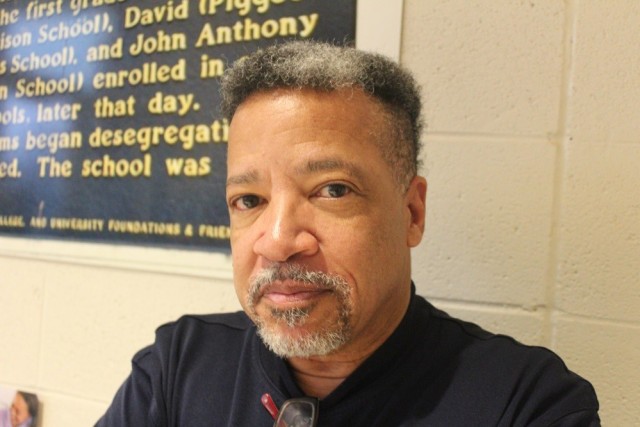

Hereford, 66, reflected on his role in history during a visit Thursday at Sonnie Hereford Elementary, a Huntsville school named in his late father’s honor. His father, who retired from practicing medicine in Huntsville, died July 7, 2016.

“I was the first Black child to integrate the schools (in Alabama) and I think one of the significant things is I had to have the right temperament to do that,” he said. “And I sometimes compare it to Jackie Robinson because it wasn’t enough to be a good ballplayer. In my case it wasn’t enough for me just to be a good student. Like I said, I have the right temperament. I didn’t want to be fighting every time somebody called me a name. So, that was the role that I played. I had to be the right one to make everything succeed.”

The Madison resident is a senior systems engineer for Five Stones Research in support of the Program Executive Office for Missiles and Space. He has worked at Redstone off and on for probably 30 years, including time with the Department of Defense and with NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

After two years at the Fifth Avenue School, Hereford attended grades three through eight at a Catholic school, the then St. Joseph’s School which subsequently became Holy Family School. His five younger sisters followed him there. He attended the ninth grade at Ed White, and grades 10-12 at Butler High, graduating in 1975.

Hereford earned a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from Notre Dame in 1979. He earned a master’s in computer and systems engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in Troy, New York, in 1985. He has two daughters: Beth Patin, a professor at Syracuse who has her doctorate from the University of Washington, and Cathy Hereford of Huntsville, and a grandson, Maren Hereford, 21, of Nashville.

He often speaks at public events, schools and churches. Hereford was the featured speaker at the “Embark on a Moment in Time” event Jan. 30 at the Orion Amphitheater.

He shared his thoughts on the importance of Black History Month.

“I think because a lot of times those stories don’t get told. And in fact, sometimes those stories are purposely suppressed,” Hereford said. “That’s why I think it’s important to get that out and tell those stories, the Black history stories.”

He shared a story from King’s visit to Huntsville in 1962. Hereford’s father escorted King to his speaking engagements.

“When (King) arrived at our old airport in 1962, there were a few dozen people there to meet him. And they asked Dr. King who he wanted to ride with,” Hereford recalled. “He looked out in the parking lot and saw a convertible Cadillac, and that was my father’s car. So, dad had the honor and privilege of escorting him to his different engagements.”

King made three main points in his Huntsville speaking engagements: the need to get people registered to vote; the importance of keeping the movement nonviolent; and the need to get the schools integrated.

“Dr. King’s visit helped to bring life back into our civil rights movement here,” Hereford said.

Social Sharing