FORT LEE, Va. — In 1950, newly commissioned 2nd Lt. Arthur J. Gregg was forbidden to step foot inside the whites-only officer’s club at Fort Lee.

Seventy-three years later, the facility bears his name.

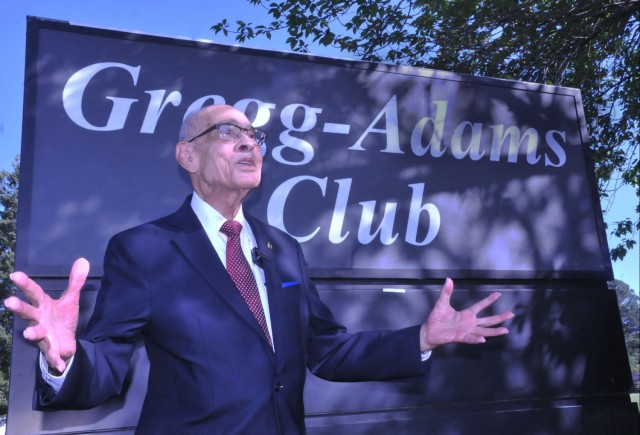

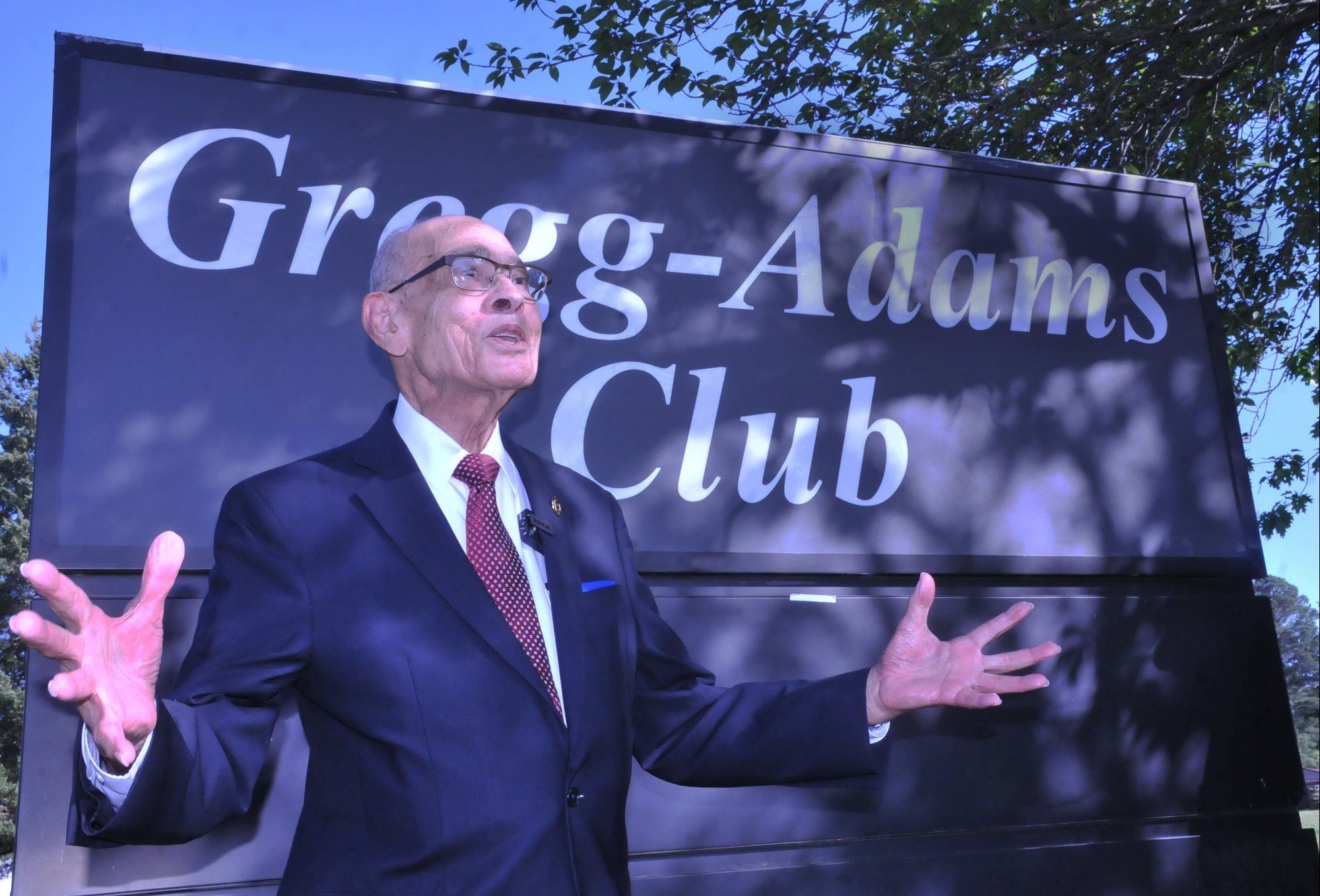

During a short, informal ceremony April 19, retired Lt. Gen. Gregg helped to unveil the revamped marquee that now welcomes visitors to the Gregg-Adams Club. The new name also honors the late Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the first Black woman commissioned through the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps — later known as the Women’s Army Corps. She achieved fame after leading the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion to incredible success during World War II.

Among those present for the unveiling were Maj. Gen. Mark T. Simerly, U.S. Army Combined Arms Support Command and Fort Lee commanding general; Col. James D. Hoyman, Fort Lee garrison commander; and Command Sgt. Maj. Tamisha A. Love, garrison command sergeant major.

The club’s name reflects the upcoming redesignation of Fort Lee, which becomes Fort Gregg-Adams April 27. The redesignations are the result of congressional legislation requiring the removal of Confederate names from Department of Defense assets, which includes eight other Army posts. The 94-year-old Gregg is the only living person among the new namesakes for these installations.

Gregg has a long and storied history with the club that began long before these recent honors. It started in 1950 when he reported to Fort Lee after graduating from Officer Candidate School. Although President Harry S. Truman had signed legislation prohibiting military segregation in 1948, some segments of the Army were slow in implementing required changes.

Specifically at Fort Lee, integration of the club was reportedly contentious. A July 27, 1951 article in the Arizona Sun went so far as to characterize the post commander as being in “open defiance” of Truman’s order, spending taxpayer dollars to build a $60,000 “colored officers club” intended to keep the $500,000 whites-only facility as it was. That project was cancelled within months of the article’s publication.

Black Soldiers also were subject to countless other injustices at Fort Lee, according to the article. In a 1981 Washington Post story, Gregg expressed general displeasure for segregationist policies during his initial years in uniform but was miffed at one in particular.

“What annoyed me most was not being permitted in the officers' club,” the logistician said.

A 1946 enlistee who grew up in the segregated South, Gregg knew full well what donning the uniform entailed for Black Americans. It meant unequal treatment and the possibility of losing life or limb for a country that did not see them as the true sum of its parts. He, like many others, mostly accepted the circumstances but worked hard and held tightly to the notion of progress.

Inevitably, change would come. Full integration was complete in 1954, according to the Army, yet it was just one of many future steps forward. Since then, the nation’s largest military service has undergone policy changes and rebranding aimed at correcting injustices and promoting diversity, equality and inclusion within its ranks. The Congressionally mandated redesignations could be considered another step toward that end.

Gregg, who held his 1981 retirement ceremony at the same Lee Club that denied him entrance three decades prior, said his 36-year career was often moved by the hope and optimism of an institution he felt could change for the betterment of all who serve.

“I always enjoy doing jobs to the best of my ability,” he once said, “but I also felt the Army was always watching my back and helping me along the way.”

Along the way, Gregg has served in Korea and Vietnam among many other locations and was appointed to several high-profile positions during his career. Subsequently, he was the first Black Soldier to earn three stars and the highest-ranked Black officer in the U.S. military when he retired.

Oddly, Gregg’s outstanding record of achievement was not conspicuous during the event, subdued by heavy measures of his affability, humility and sense of dignity.

Minutes after the unveiling, Simerly, Hoyman and Love escorted the general to the club for a brief social. An aura of reverence was evident as nearly 100 Soldiers and civilians lined both sides of the walkway leading to the entrance. Rather than walking straight into the club, Gregg, visibly moved by the turnout, took the time to shake hands and speak with nearly every person in attendance.

As he reached the short steps that lead into the stately facility, one Soldier there apparently cautioned him to watch his footing. “Oh, I’m going to make it,” he replied with a smile, continuing to shake hands and speak with others lining the stairs. Upon reaching the top of the stairs, standing feet from the door of the club for the first time as its namesake, the good-natured retiree elicited delighted laughter from the crowd when he announced: “I made it!”

Capt. Theodore Dalley was one of those who came out to see Gregg. The commander of Whiskey Company, 244th Quartermaster Battalion, said meeting an installation namesake is a once-in-a-lifetime event.

“This is a part of history,” he said. “It’s a monumental occasion.”

Dalley added that Gregg is deserving of the honor.

“It’s the culmination of all the hard work and dedication throughout his life,” he said. “All of his achievements have come to this. His legacy gets to carry on forward for years and years to come.”

Staff Sgt. Chelsea Wood also came out to bear witness to the event.

“I wanted to be here in person to see it happen,” said the Soldier, who is assigned to the 111th Quartermaster Company.

Wood also was enthralled with the idea that something can be flipped on its head.

“He couldn’t be a part of a club when he served,” she said, “and now, the club is named after him."

“It’s pretty awesome to see that change.”

Imagine what it’s like for Gregg.

Social Sharing