In recent decades, the increasing number of women in the U.S. Army has strengthened the service in innumerable ways. The road to where we are today, with almost 6% of Army rotary-wing aviators female and almost 15% of the entire Army female, has been a long one.

In the American Civil War (1861-1865), women were not allowed to officially serve in the military, so they volunteered by cooking for troops, mending and washing clothing, and taking care of the wounded. Around 1918, after the start of World War I, the number of women in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps skyrocketed from around 400 to more than 3,000. According to the United Service Organizations, this was the first time women were allowed to officially serve in a fight involving our nation. Also during World War I, the Navy notably recruited women to serve in non-combat positions after finding a loophole in the Navy Act and established the “Yeomanettes,” who served in clerical roles. The U.S. Army Signal Corps followed suit, recruiting women to serve as telephone switchboard operators.

In 1943, the Women’s Army Corps was established allowing women to serve as official members of the U.S. military for the first time (rather than as volunteers, as they were previously) during wartime, particularly during World War II, with an expiration date on the Corps set for 1948. At this time, more than 350,000 female Service Members joined in the fight to perform non-combat roles. Picture “Rosie the Riveter,” the iconic image of a woman revealing her bicep, wearing a jumpsuit and a red bandana, to represent the many women who took on non-traditional jobs in the absence of men who were off fighting the war.

Under President Harry S. Truman, in 1948, the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act was signed, instating the Woman’s Army Corps as a full-time part of the Armed Services in an official capacity, during peace and wartime. With the looming Korean war, the number of female Service Members surged yet again. Notably, in this same year, 1948, President Truman also desegregated the Armed Services, allowing people of all colors to serve together.

Even though women were allowed to serve in the military in an official capacity following the signing of the Act, their roles were still severely limited. Even in the Vietnam War, which followed, 90% of the 11,000 women who served overseas did so as nurses.

During the conflict in Vietnam, Sally D. Murphy was in Army Aviation School at Fort Rucker, Ala., and would eventually become Col. Sally D. Murphy, the Army’s first female helicopter pilot. Murphy graduated from flight training on June 4, 1974. Murphy paved the way for future decades of female aviators, although women would not be allowed to fly in combat missions until 1989 and to engage in ground combat missions until 1994. Despite the strides made by female Soldiers like Murphy throughout the decades, and by Army leaders in ensuring women had the opportunity to serve, the safety standards of military vehicles and materials, particularly rotary-wing aircrafts, have not yet caught up to match this emerging population of pilots.

U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory researchers are working to close this gap by providing data-driven recommendations to update the military safety specification that governs how seats are designed for U.S. Army helicopters. The current helicopter seats are developed following Military Specification 58095A, which was first established in 1971 and was last updated in 1986. The seats are designed to absorb/reduce energy of an impact, providing protection to the occupant from spinal injuries. The specification states that in a crash, a seated occupant in an Army helicopter should be exposed to no greater than 23 Gs of acceleration. The acceleration limit is based on documented human tolerance to whole-body accelerations.

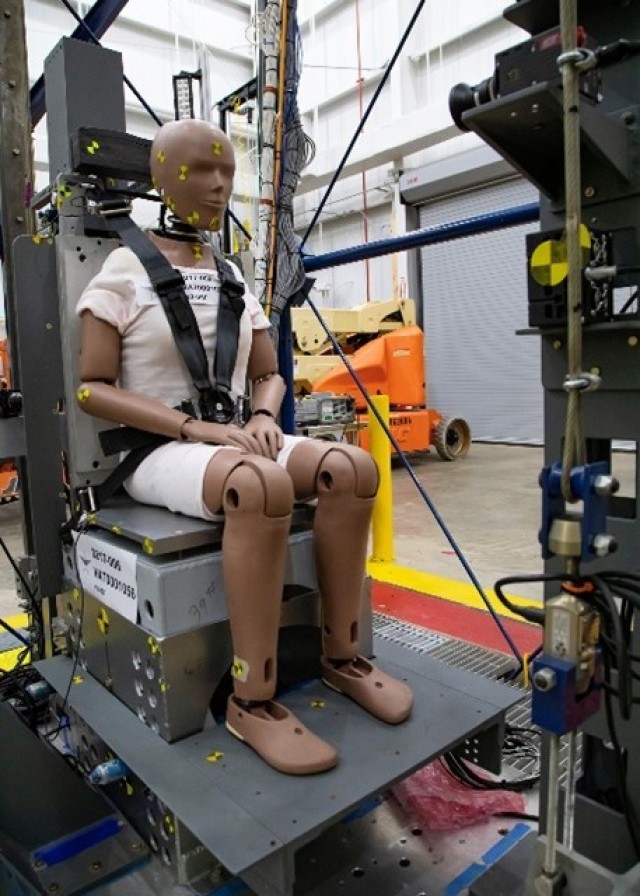

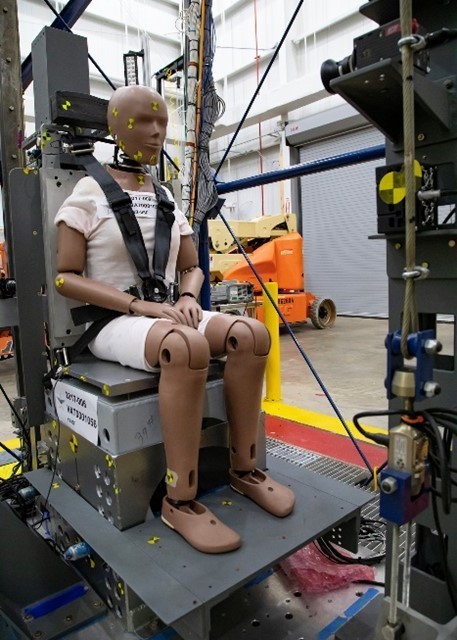

According to the Principal Investigator on this effort, USAARL engineer Katie Logsdon, epidemiology reviews of U.S. Army helicopter mishaps concluded that the current specifications were not protective enough; too many occupants were still suffering spine injuries in Army helicopter crashes. “The seats need to absorb more energy to protect the occupants,” explained Logsdon, “so the team started conducting vertical acceleration tests with anthropomorphic test dummies that were equivalent in weight to the 50th percentile male at 199 pounds.” The dummies were instrumented with sensors to collect response data, including acceleration, force, and moments, and placed on a rigid seat (one without any energy absorbing materials) with a 5-point restraint. The USAARL vertical acceleration tower was used to simulate dynamic events (crashes) and collect the response data collected by the sensors on the dummies. After collecting the dummies’ response to the exposure, the researchers then had the task of correlating the impacts experienced by the dummy to that of humans. This analysis provides the data needed to support recommended updates to the specification.

The researchers at USAARL didn’t stop with the average sized male in their testing, they recently completed the testing described above using a female dummy at a weight closer to the lowest female average (110 pounds), a breakthrough and a first in the effort to make Army aircrafts safer for growing numbers of female pilots. There are physical differences between male and female bodies that make this complicated. According to Kim Vasquez, a member of the research team at USAARL “one of the main differences is in the geometry of the pelvis between males and females. Female bodies are not just scaled down versions of males, they have different shapes, different seating postures, and they carry weight differently.”

The intricacies of the effort are no challenge to the group taking it on; they don’t shy away from the tough questions. They are committed to enhancing the protection and performance of aviators of all shapes and sizes. According to Logsdon, “At USAARL, our main goal is to protect the Soldier. Historically, the focus has been on the male, but the number of female aviators is increasing, and it is time to consider those differences in the mechanisms we have to protect them.” Once testing is complete, the recommended updates will be provided to the designers of the Future Vertical Lift aircraft to ensure representation of all Warfighters in the future fight.

About the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory.

The U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory is a world-class organization of subject matter experts in the fields of operator health and performance in complex systems; the en-route care environment; blunt, blast, and accelerative injury and protection; crew survival in rotary-wing aircraft and combat vehicles; and sensory performance, injury, and protection. USAARL engages in innovative research, development, test and evaluation activities to identify research gaps and inform requirements documents that contribute to future vertical lift, medical, aviation, and defense health capabilities. USAARL is a trusted agent for stakeholders, providing evidence-based solutions and operational practices that protect joint force warriors and enhance warfighter performance. USAARL invests in the next generation of scientists and engineers, research technicians, program managers, and administrative professionals by valuing and developing its people, implementing talent management principles, and engaging in educational outreach opportunities.

Social Sharing