ROCK ISLAND ARSENAL, Ill. — February is Black History Month, a time dedicated to celebrate the courage, strength, contributions and legacy of Black Americans who helped shape the world we live in today.

Black History Month traces its origins to 1915, when historian Carter G. Woodson and Minister Jesse E. Moorland founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, today known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

The organization’s purpose was to research and promote achievements by Black Americans and other people of African descent and started sponsoring a national Negro History Week on the second week of February in 1926 to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

By the late 1960s Negro History Week evolved into Black History Month, partially thanks to the civil rights movement and an increasing awareness of Black identity.

The month of February was officially designated as Black History Month by President Gerald Ford in 1976. Ever since, the United States and other countries in the world, including the United Kingdom and Canada, have devoted a month to celebrating Black history.

Going back a little over a century, we can trace contributions that Black American Soldiers made at Rock Island Arsenal during the Civil War.

“By July of 1862 the American Civil War had fully engulfed the nation and almost every American citizen and industry were being impacted by the demands of the war,” said Kevin Braafladt, U.S. Army Sustainment Command historian.

“Due to ever increasing need for manpower and calls from abolitionists and sympathetic followers, there was a growing movement calling for the United States Congress to allow African American men to serve within the federal military.

“After passing a series of acts such as the Confiscation Act of 1862 — which freed slaves whose owners were in rebellion against the United States, the Militia Act of 1862 — which gave more authority to allow former slaves to be employed, in any capacity, by the Army and the Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, the time was finally right,” Braafladt said.

The United States War Department issued General Order 143 in 1863, which established the Bureau of Colored Troops, which began recruiting Black American men to serve in all branches of the U.S. Army.

In total, more than 178,000 free Black American men — about 10 percent of the total Union fighting force — would serve in the remaining two years of the war, in a variety of capacities within the Army including infantry, cavalry, engineers and artillery from every state within the Union.

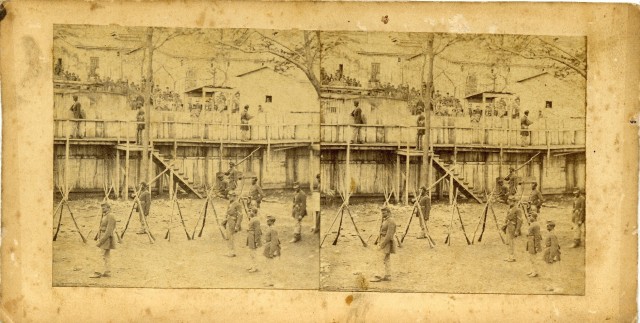

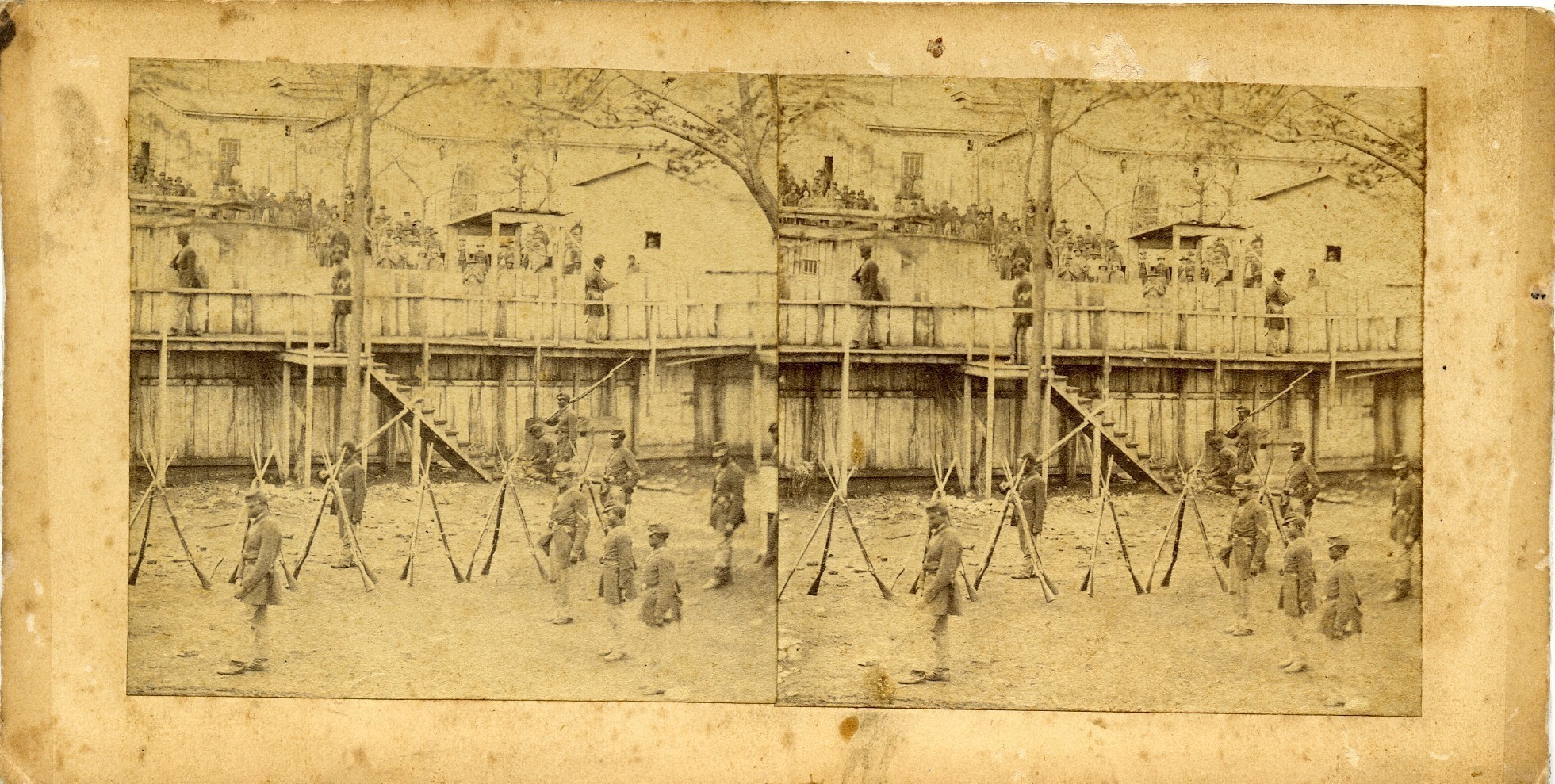

Braafladt said that the 108th United States Colored Troops was one of the many regiments formed during the war. Organized at Louisville, Kentucky, in 1864, the 108th United States Colored Infantry Regiment consisted predominantly of formerly enslaved men from Kentucky, as well as some free men. After garrison and guard duty at various points in Kentucky, the regiment was transferred to Rock Island Prison Barracks at the newly established Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois.

“The 108th served as guards at the Prison Barracks that held Confederate prisoners of war, which created an uproar among the prisoners. Their time at RIPB was not easy duty due to a number of different fatigue assignments dealing with the prisoners and trying to handle disease outbreaks,” said Braafladt.

In the first few weeks after arriving, more than 200 of the 108th Soldiers reported sick or not fit for duty. About 40,000 Black Soldiers died in the war: 10,000 in battle and 30,000 from illness or infection.

“Private William English was the first Soldier from the regiment to die at RIPB with 53 others joining him during the nine-month assignment,” he said. “Many of them are buried at the present-day Rock Island National Cemetery.”

In May 1865, Regimental Order 69 was issued, and the 108th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment left Rock Island on board the Riverboat “Maria Denning”, arriving at Vicksburg, Mississippi, 11 days later.

The Rock Island Argus wrote of the unit’s departure: “The 108th USCT have conducted themselves with great propriety since they were stationed here.”

Additional Black Soldiers who were later recognized for their service at the arsenal include Sgt. Kendrick Allen, Pvt. Milton Howard and Cpl. Kager Mays.

Kendrick Allen was born enslaved in Anderson County, Kentucky. Evidence suggests that he escaped to join the Union Army in 1864 and spent two years in the 108th USCT at various posts — Including as a guard at RIPB.

A note that his commanding officer wrote praises Allen as an excellent Soldier — an outstanding compliment to a then 18-year-old sergeant with no prior military experience.

Milton Howard was born in Muscatine, Iowa, in 1852. Shortly after his birth, his family was abducted and sold into slavery in Alabama. He eventually escaped and enlisted in the Union Army in 1864, serving as a private with Company F, 60th U.S. Colored Troops.

He was injured several times, and after the war he returned to Iowa. He began working at Rock Island Arsenal in 1866 and was one of the first black workers employed there.

His 56-year career inspired years of civil and military services in his family. When he died in March 1928, his death was front page news in the Quad Cities. In 2018, a street at RIA was named in his honor.

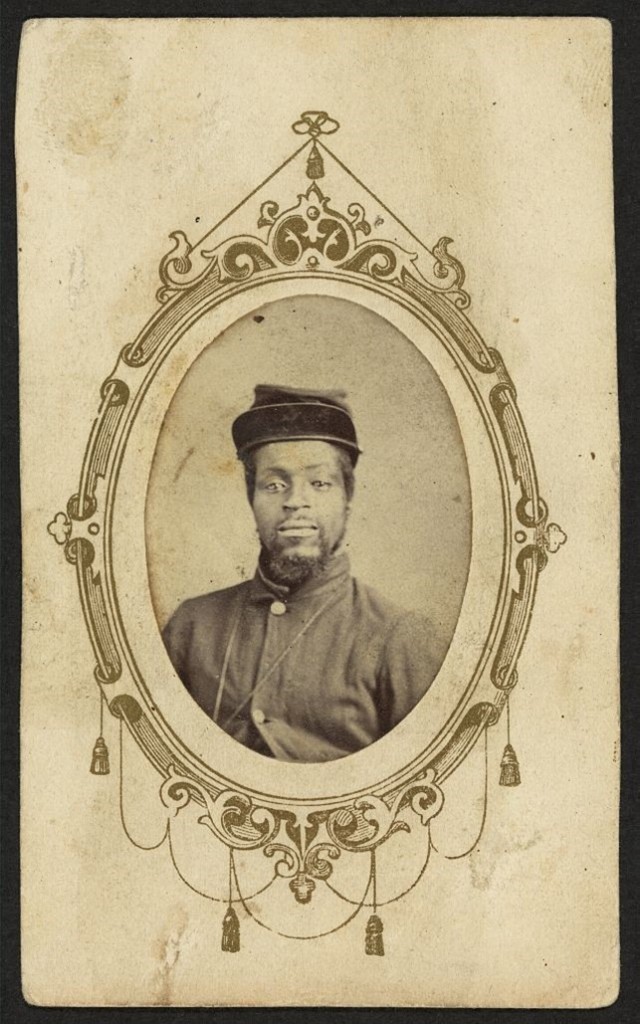

Cpl. Kager Mays was 40 years old when he enlisted in the U.S. Army in June 1864 at Lebanon, Kentucky, and arrived at RIPB shortly after being assigned to the 108th USCT.

“Based on his service record, Mays was an exceptional Soldier, rising to the rank of corporal by December 1864,” said Braafladt.

When the 108th USCT was later assigned to Mississippi, Mays contracted and died of “remittent fever,” most likely malaria or yellow fever, in August 1865.

Mays has no known grave marker. It is thought he is in an unknown Soldier’s grave in Vicksburg, Mississippi. His photo is retained at the Library of Congress and his service record resides in the National Archives.

Social Sharing