VIEW ORIGINAL

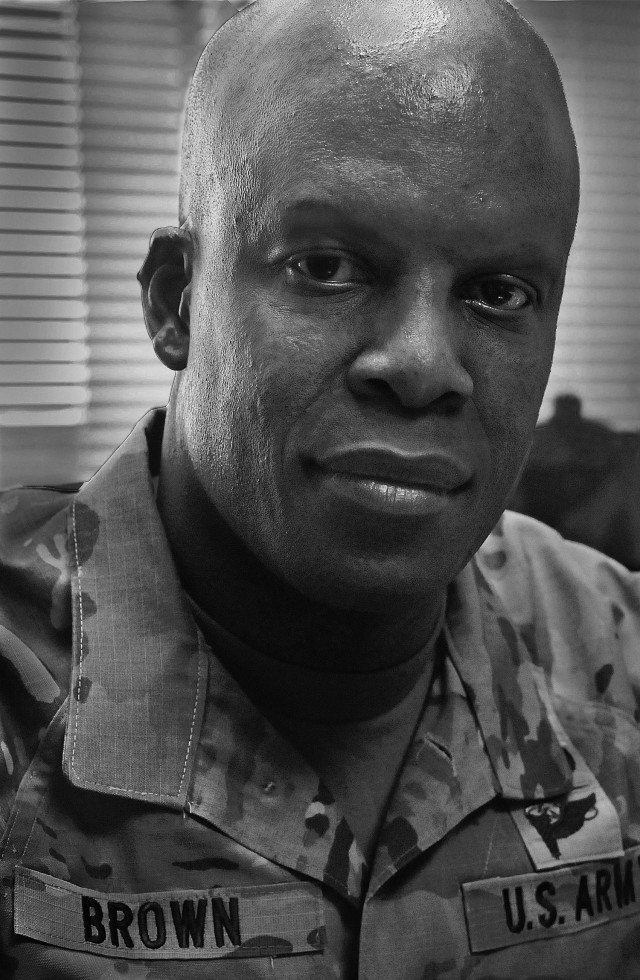

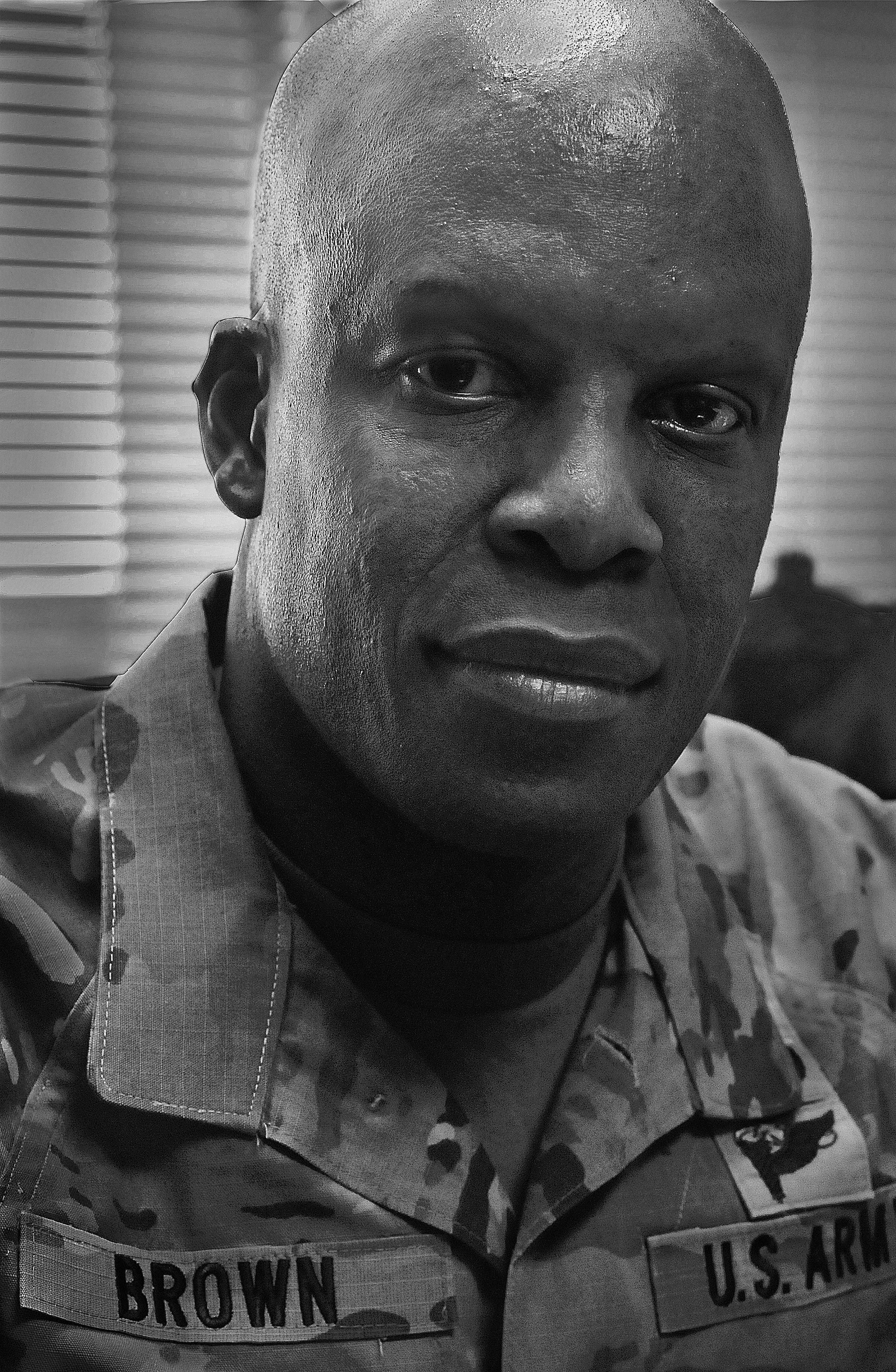

FORT LEE, Va. – Command Sgt. Maj. Randy T. Brown’s intense determination is hard to ignore.

It’s the palpable feeling one gets when looking him in the eye and hearing his aspirations as the newly installed senior enlisted leader for the Army Transportation Corps. The 47-year-old who rose through the ranks as a motor transport operator exudes confidence and undeniable focus.

Put in his words, “I’m unapologetically driven, afraid of failure and someone who lives within his purpose.”

Brown took over duties as the 15th TC CSM in mid-July. He came to the Sustainment Center of Excellence packing a potent force of will – someone clearly prepared and elated to tackle issues large and small hovering within the transportation universe.

Speaking about his new leadership perch, he said, “There is an appreciation mixed with humility, and those two ingredients equate to joy, just pure joy. I’m excited.”

He is part a leadership team led by Col. Frederick L. Crist, Chief of Transportation, also a newcomer this year. Chief Warrant Officer 5 John J. McCartin serves as the TC Regimental CWO. The trio oversees the education and training of thousands that come through transportation schoolhouses annually, and develops doctrine and ensures the success and welfare of more than 64,000 TC troops in the active and reserve components.

Just like other branches, the Trans. Corps has numerous pressing issues – including driving change to ready itself for largescale combat operations – and management of human resources as an overall component of readiness is part of that framework. Chief among its efforts is the Taking Care of People initiative.

“That’s not just a bumper sticker,” said Brown of the name and program based on an Army-wide plan of action. “We do have solemn and tender care for our team members. It starts from the time we walk in the door (of a place of duty). We want everyone to feel like they’re a part of the team and their voice matters. It takes two seconds to make someone’s day.”

The Trans. Corps also is investing in Soldier and civilian development, said Brown, who last served as the 599th Trans. Brigade CSM in Hawaii. They’re using the power of influence, among other steps, to relate and empathize with others while promoting professional development.

“As senior leaders, we have experienced things our subordinates have not,” Brown observed. “It’s important to reach back and share those experiences and use them as tools to further develop future leaders.”

The corps’ official initiative of “driving change” also fuels the engine behind Brown’s personal agenda that addresses parochialism as a load of unwanted cargo on the corps’ journey into the future.

“It (parochialism) has been an inhibitor for a long time,” he said. “Although change is a tool of evolution, for those who live within that place of comfort, it requires them to leave a place of familiarity and go to a place of uncertainty. It’s a tough transition, but the world has changed. We can’t afford to sit on our front porches and declare, ‘We’re not going anywhere’ while the world turns.”

Brown acknowledged parochialism as an issue with the potential to undercut modernization and war-fighting initiatives.

“The days of driving a truck from point A to point B and waiting for someone to offload it are over,” he said. “(People in that mindset) are a liability on the battlefield. (Transporters) need to not only deliver readiness but also enhance it by availing (themselves) to perform tasks such as helping to establish security. If we don’t get out of this parochial mindset, we will become irrelevant.”

Brown – who said he is “nobody’s truck driver” but rather a “force-multiplier” – declared he is ready to take action, yet he is pragmatic about expectations. Declining not to reveal strategies, he said change “is not going to happen overnight and not (entirely) during my tenure.”

“The thing is to get it in motion and … down the road so it is part of the rhythm,” he said. “I want to get it up the hill so it is on its way and continues forward.”

The Trans. Corps, smallest among Combined Arms Support Command logistical elements, is headquartered at Fort Lee. Its MOS-producing schoolhouses are widely dispersed – most of them at Joint Base Langley-Eustis and the largest number of transporters trained at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo.

Motor transport operators dominate the branch. Also amongst its ranks are transportation management coordinators, cargo specialists, mariners and railway operations crewmembers who serve in diverse units throughout the Army.

As of late, the corps’ priority is fine-tuning how it supports largescale combat operations, the Army’s newest warfighting focus. Brown said there are processes in motion pushing it to that end.

“We’re constantly assessing,” he said. “We’re getting much through feedback – talking to commanders and leaders in the field. Feedback is an absolute gift. Things are constantly evolving. The unfortunate piece is there are times we find it difficult to respond to changes. Change within the institution is like turning around a vessel. It takes time.”

Regarding the work required to address the corps priorities, Brown said he comes to Fort Lee armed with the cognizance there is not much room for failure.

“Knowing my sphere of influence can impact transporters across the globe,” he said, “I absolutely need to keep in mind what can transpire due to my actions, behaviors and the way I lead.”

Brown, a former Marine, said while the CSM’s office is influential, it still requires engagement.

“I often talk about the three ‘ships’ – friendships, partnerships and relationships,” he said. “I’ve been able to leverage my relationships with the various sustainment and warfighting functions over the years. Every opportunity I’m in a room with them has been used to further our connections.”

It does not hurt that Brown has a reputation as a topnotch Soldier. Retired Command Sgt. Maj. Cynthia B. Howard worked with him when she was the 12th TC CSM and considered him as a professional, compassionate and inspired Soldier. The selection for his current billet came as no surprise.

“I knew through all of his hard work, dedication and commitment he showed to others that he would one day, too, fill my shoes,” she said.

Where Brown is today, though, differs from the initial years of a military journey undertaken by a young man who grew up in the decadence of Paterson, N.J., and later Montgomery, Ala., and was becoming a subject of interest to law enforcement.

Later in his career, there were dark moments as well. During a 32-month tour at Camp Casey, South Korea, ending in 2019, Brown said he struggled with isolation. His was unaccompanied by family and duty demands intensified due to a contentious relationship between the U.S. and North Korea. Alcohol became the means to cope until a moment of reckoning at the height of his troubles enabled him to adjust perspective.

“I simply took a look in the mirror, and said, ‘This is not how you deal with it,’” he recalled. Brown unpacked his behavior, then dove headfirst into a vow of abstinence and plans to support others grappling with substance abuse.

“I completely stopped drinking, then turned my struggles into triumph … volunteering at the in-patient facilities for those with dependence,” he recalled.

It was redemptive and self-actualizing. Brown would not hide behind veils of secrecy or lean against walls of hypocrisy concerning his substance abuse. It happened, and it happened to a high-ranking, senior enlisted Soldier, plain and simple.

“I don’t apologize to anyone for what I went through,” he said. “It’s part of … who I am. It also helps me to connect. … I can put my hand on any leader and say, ‘I’ve been there. It’s OK. I know you’re going through some things.’ You might not say anything, but I’m here if you need me.”

Brown refutes any assumption that individuals who openly associate themselves with substance abuse or mental hardships are tarnishing their leadership image due to that show of vulnerability.

“I think it takes strength. Strength to tell someone ‘I struggled at a point in my life,’” he said. “Don’t get it twisted, though. Just because I have struggled, don’t look down on me because you want the perception you’ve never struggled. We’ve all struggled, and we all carry things with us.”

Brown also spoke about balance, saying individual and family well-being promotes higher performance and is key to the longevity of the average Soldier’s career.

“We talk about taking care of family and people first, but as senior leaders, Soldiers need to see us taking care of family,” he said. “They need to see us balancing our work lives.”

Brown is demonstrable in moving the dial. He has refrained from sending late-evening email blasts, particularly heading into the weekend, with the customary premises of “Hey, I know you’re about to head home, but I’m just giving you a heads up …”

“There is no ‘heads up!” he exclaimed. “It can wait until tomorrow.”

Furthermore, Brown understands subordinates take cues from leader actions and behaviors. For example, most troops will not depart at the end of the duty day until the leadership does so. He sees it as a rooted tradition that requires modification if it ever is going to change. He offered the following alternative:

“OK, I’m going to go home at 1600 hours and spend time with my daughter,” he said, “but instead of coming in at 0800 the next day, I’ll come in at 0700 as an adjustment.”

Work-life balances, Brown further noted, constantly needs to be assessed, and Soldiers need to listen to teammates at work and at home.

“If your spouse tells you too much work is being bought home, it’s probably true,” he said. “I had a great practice when I was a first sergeant. I would come to work in civilian clothes, and change to my uniform there. When it was time to go, I’d take the uniform off at the job and go home in civilian clothes as Randy. That’s what my daughter saw.”

Brown said he often used his return commute as time to decompress, preparing himself mentally to interface with his daughter as a father. That relationship has been inspirational in many ways. He used the acronym DAD – discipline and dedication – to denote his devotion to her and the Army.

“It helps me keep thoughts of my kid, which generates positive energy, giving me the drive to go out there to be the best sergeant major I can be,” he said.

Brown has plenty of intense determination to do that.

For Brown’s full biography, visit https://transportation.army.mil/Bio%20files/regt_csm.html.

Social Sharing