WASHINGTON -- Soldiers representing the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community virtually celebrated Pride Month Thursday as part of a discussion that marked another step in the Army’s growing recognition toward the LGBTQ community.

The participants shared personal stories and experiences, as well as equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts taken by the Army, along with how the policies have impacted their lives. The Soldiers also discussed the importance of LGBTQ representation within military ranks.

Every June, Pride Month is a national observance that is held to commemorate the Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan, New York, in 1969, a historic tipping point within the gay liberation movement to empower all LGBTQ Americans.

Since then the LGBTQ community has made significant progress toward equality. However, with change have come setbacks.

In 1993, the Department of Defense Directive 1304.26, commonly known as Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, or DADT, was written into law. The directive was a compromise measure that barred LGBTQ-identifying persons from military service, but also prohibited military personnel from discriminating against, or harassing, closeted gay and lesbian troops.

In 1984, when Maj. Rebecca A. Ammons, a transgender Army chaplain, first enlisted as a Marine, DADT did little to change her life. Even in 2011, after lawmakers repealed the directive, the repeal only ensured gay, lesbian and bisexual troops could openly serve. It did not permit transgender service members from serving.

“[DADT] wasn’t even an issue” in the 80s, she said during the panel discussion. “I was explicitly asked on my [enlistment] forms: Are you gay? Of course, there wasn’t even a block to say: Are you trans?”

Despite that, “I had this overwhelming compulsion; this need to serve,” Ammons said. Yet, with that need came “this overwhelming feeling of isolation.”

Two landmark events came years later. In 2015, the repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act allowed all Americans, including service members, to marry their same-sex partners in all 50 states.

Before this, a handful of states legalized same-sex marriage. Since 2013, all same-sex spouses were eligible to receive identification cards and all associated benefits.

Another milestone within the military came earlier this year with a policy that allowed transgender individuals to openly serve.

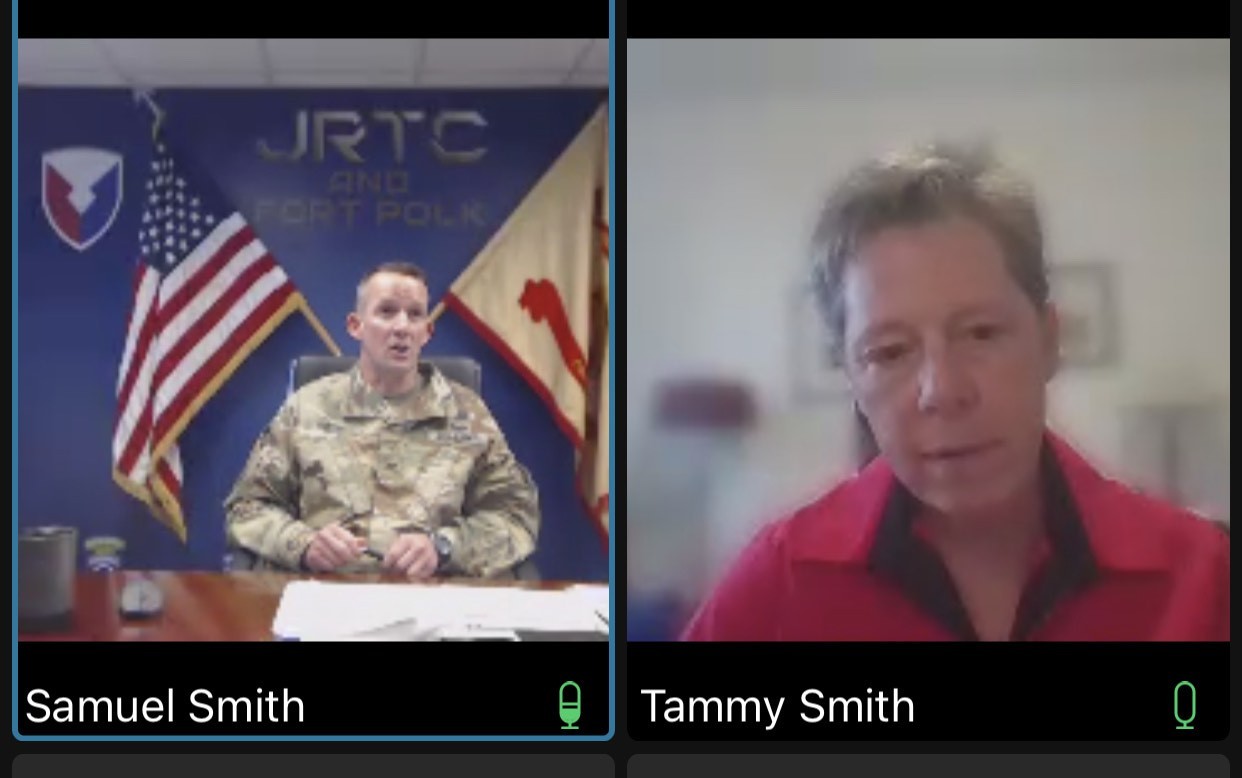

These changes are reflective to the Army’s direction of putting “people first,” said retired Maj. Gen. Tammy Smith, moderator of the event.

Smith, who retired earlier this month, helped forge the Army’s People Strategy, which focuses on individual Soldiers and how to deliberately manage their skills, improve their overall quality of life and develop a modernized talent management system.

“I had the privilege of working on the Army’s People Strategy and the quality of life portfolio,” Smith said, in her opening comments. “This is a tangible example that the Army means it when they say ‘people first.’ Our strength comes from diversity.”

For the retired general, the purpose is simple: an inclusive Army means a more lethal, stronger force, she said.

“We’ve come a long way as an institution. I think it’s important that we have people first, as far as a great No. 1 priority,” said Col. Samuel P. Smith Jr., garrison commander of Fort Polk, Louisiana.

Truth seemed to be the theme of the night, as each panel member shared their own personal journey. The panel showcased an array of Soldiers, each with unique experiences and backgrounds, and who, according to the moderator, were examples of what the Army of today represents.

Among the panel members was Ammons, who said the fear of coming out as transgender weighed heavily on the chaplain’s shoulders. Ammons recalled the trepidation she felt when coming out to her peers, especially within a faith-based community she serves. She worried how they would respond to the news, she said.

Ammons publicly came out last July and with it came her name change and the aggressive medical procedures she planned to go through for her transition. She was surprised by how “heartwarming and honestly amazing” her fellow chaplains and other Soldiers have treated, and continue treating her, she said.

But isolation still happens. That feeling, whether caused by orientation or gender, can be “incredibly isolating and damaging,” said Master Sgt. Ijpe DeKoe, an Army reservist who was among the plaintiffs linked to the Supreme Court decision on same-sex marriage.

“It took me years to understand that kind of trauma. Years later when I look back, I’m very troubled by anyone who has to go through that for whatever reason,” he added.

Finding support

One way to overcome isolation, according to the panelists, was finding the right support group.

“It took me a while [to be true to myself],” Col. Smith said. “I had a close circle of friends who helped me through it, which is important if you are isolated, so I was very fortunate to have a very close circle of friends who helped me along this journey.”

For years, Col. Smith struggled with his orientation. In 2004, amid DADT, he knew it was time to be honest with himself, to be honest with the girl he was dating and to his family, he said. However, the missing piece was his career. Outside of his small support group, he could not be open to the Army.

He questioned whether or not he could endure 20-plus years in the Army while internally struggling with his orientation. “I didn’t know whether the two could align: me being gay and serving in the Army,” he said.

Even when he came out to his friends and family, the colonel still felt closeted at work. He couldn’t talk about his boyfriend. Instead of saying his partner’s name, he used a traditional girl’s name with the same first letter. He couldn’t have certain pictures on his desk. He couldn’t talk about his weekend plans with coworkers.

“I love the Army, and I was a good [Soldier],” he said. But “I could not be myself.”

Instead, Smith “got used to it,” he said. “That’s just the way things were. I accepted that.”

As time passed, the colonel became more confident in his orientation. “As I matured, I realized I [wasn’t] being authentic and at some point, I think people are going to see through me, and some leaders did that,” he said.

Not only did he feel transparent, but Smith also felt like he owed it to the people he worked with, his subordinates, and himself to stop being fake. “I had to be authentic, or it was going to cost me my career,” he said.

Once DADT was overturned, “it was like a big weight lifted off your shoulders,” Col. Smith said, no longer feeling like he had to think carefully about how he discussed his love life to ensure he followed DADT policy.

‘Be visible’

Despite mostly upbeat cheerfulness displayed during the panel, the Soldiers understood the challenges closeted Soldiers, not be ready to come out, may feel.

“Understand that this environment is open and inclusive and it welcomes you,” said Capt. Julian Woodhouse, an officer in charge of the 315th Military History Detachment in Manhattan. “As long as you work on your internal value and your internal love for yourself, because that’s the biggest enemy we all face.

“Be visible so that Soldiers who are also queer [or questioning] can feel comfortable seeing someone in leadership,” Woodhouse said. “They can be proud of who they are and not having an issue with communicating that.”

Capt. John Cloutier, a cyber officer with the 780th Military Intelligence Brigade, echoed Woodhouse’s sentiment to closeted Soldiers. “Be visible, but not everyone is going to want to have lunch with you or talk about their deepest feelings,” he said.

“Some people may not be comfortable putting a picture on their desk. But do something as simple as mentioning what you did over the weekend, using the right pronouns because people pick up on that stuff,” he said.

“The more we are visible, the more people will realize there are LGBT people all around, and it is OK,” Cloutier added.

According to Ammons, the first step for all Soldiers should take, regardless of orientation, is simply to understand each other, “as opposed to judging and putting people in a box,” she said. “We need to learn to listen and understand.

“People who identify under the greater LGBTQ umbrella, and those who don’t, whether allies or adversaries, need to take the time to understand each other first,” she said. “Meet me as a human. I will meet you as a human first, and we can figure out the other stuff later.”

Related links:

Social Sharing