Though full integration of the U.S. military was not established until the middle of the 20th century, African Americans have served in American conflicts since before the United States was a free nation. Over time, the presence of black soldiers, sailors, regiments, and squadrons would grow until the value and importance of African American servicemen and women could no longer be ignored by leaders bent on resisting change.

Formal African American service in the American military dates from the Revolutionary War. Many freemen and some slaves already served in Northern colonial militias to protect their homes during conflicts with indigenous tribes. The service numbers rose in 1770 in response to the death of Crispus Attucks, an African American believed to be the first casualty at the Boston Massacre. While George Washington was initially reluctant to recruit black soldiers, military necessity later made him relent.

The most prominent African American soldiers in the American Revolution served in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, which recruited enough black and Native American soldiers to form more than half of its 225-man total. It was the only regiment in the Continental Army to have segregated units. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment had its most noteworthy action protecting the Colonial withdrawal from Aquidneck Island during the Battle of Rhode Island (August 1778).

Southern colonies, fearing that arming slaves would lead to revolts, opposed the use of slaves in Patriot militia, though some would serve in isolated instances. The British, however, recruited heavily from the South, promising freedom to any slave who fought for the Loyalist cause. Consequently, while an estimated 9,000 black soldiers and sailors fought for the Continental Army, nearly 20,000 fought for the British.

After the Revolutionary War, African Americans were pushed out of military service. The Federal Militia Acts of 1792 specifically prohibited black service in the U.S. Army. As a result, few African Americans participated on the side of the United States during the War of 1812. Only Louisiana was allowed to have separate black militia units in that conflict. Due to a manpower shortage, the U.S. Navy accepted free black recruits in that conflict, making up 15% to 20% of Navy manpower. Many slaves also served in the British Navy in anticipation of gaining their freedom.

During the Civil War, the Union formally established and maintained regiments of black soldiers. This became possible in 1862 through passage of the Confiscation Act, which freed the slaves of rebellious slaveholders, and the Militia Act, which authorized the president to use former slaves as soldiers. President Lincoln was initially reluctant to recruit black soldiers. This changed in January 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring freedom for all slaves in Confederate states.

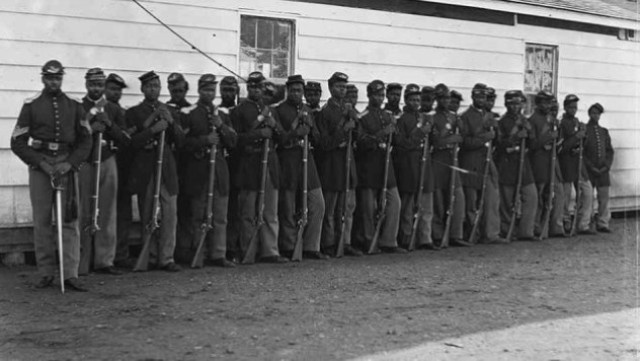

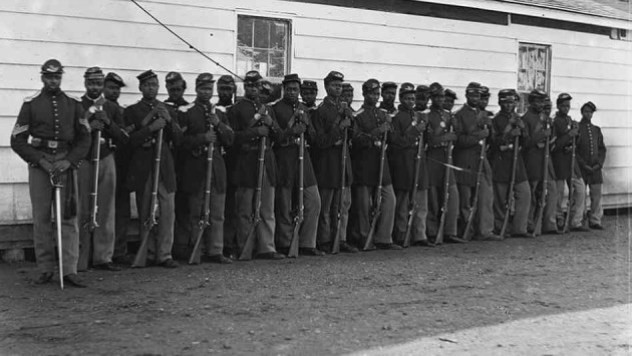

The first black regiments to serve in the Civil War were volunteer units made up of free black men. In May 1863, the War Department established the Bureau of Colored Troops for the purpose of recruiting from the African-American population. Existing volunteer units were converted into United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments. By the end of the conflict, there were 175 USCT regiments, containing 178,000 enlisted soldiers, approximately 10% of the Union Army. Sixteen USCT soldiers earned the Medal of Honor for their Civil War service. More than 18,000 African American men and three women served in the U.S. Navy, making up 20% of sailors.

Black regiments were formed in every Union state. While mostly made up of African American soldiers, other minorities served, including Native Americans and Asians, while white Union officers served as commanders. USCT regiments participated in all aspects of the war effort as infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineers, but often served as rear action garrison troops. USCT regiments served heroically at the Battle of the Crater (Virginia), the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm (Virginia), The Battle of Fort Wagner (South Carolina), and the Battle of Nashville (Tennessee), and were present when the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox. Seven African American sailors and eighteen soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their efforts in the Civil War.

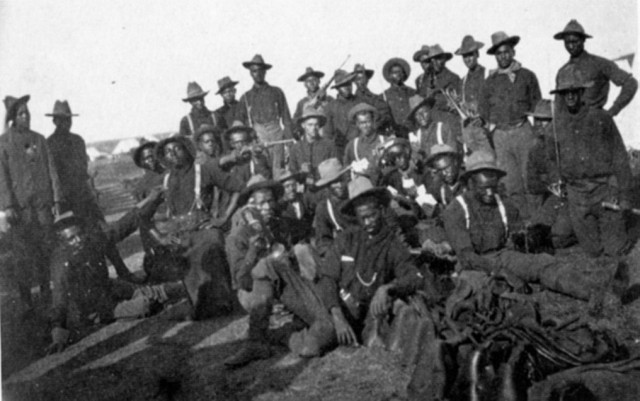

After the war, Congress reorganized the U.S. Army into ten cavalry regiments and forty- five infantry regiments. When the Army pared back to twenty-five regiments of infantry in 1869, the four black infantry regiments were consolidated into two. These regiments, the 24th and 25th, which came to be known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” were posted in the West and Southwest, mainly to battle Native Americans. Buffalo Soldiers would serve in the United States military for the next fifty years, primarily in the Indian Wars of the 1890s, for which thirteen enlisted men and six officers received the Medal of Honor.

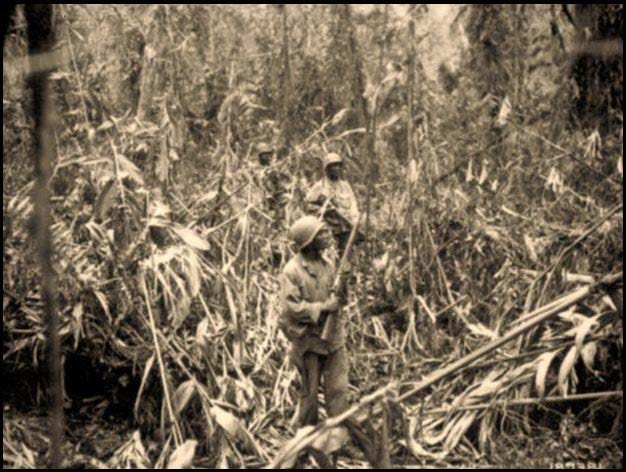

In April 1898, following a period of rising tension over Spanish treatment of native Cubans, the United States declared war on Spain. While the Navy had enough manpower, the Army had only 28,000 men in uniform. Enlistees, volunteers, and National Guard units soon added 220,000 soldiers, including 5,000 African American men, but the only black troops who fought in the Spanish-American War were the Buffalo Soldiers. The bloodiest and most well-known battle in Cuba was the Battle of San Juan Hill, during which, the most difficult fighting fell to the Buffalo Soldiers, five of whom received the Medal of Honor. These regiments would go on to fight with distinction in the Philippine-American War (1899-1903), Mexico and World War I (1916- 1918), and World War II (1944-1945).

Many African Americans joined the U.S. military after American entry into World War I, but most would not see combat. Of the 200,000 African Americans who served in the regular Army, most did so in support roles within segregated units, while 170,000 never left the United States. There were notable exceptions. The 369th Infantry Regiment (“Harlem Hellfighters”) fought alongside the French Army for six months, for which 171 members of the regiment earned the Legion of Merit. One member of the 369th also received the Medal of Honor, one of only two African American recipients of the award from World War I.

During World War I, African American service in the Navy was restricted to support duties, though ships remained integrated. After the war, the Navy banned black recruitment until 1932. By 1940, the Navy had 4,000 African American sailors, just 2.3% of its total manpower. This number increased to more than 5,000 in early 1942, but black sailors were still relegated to service as stewards, waiters, cooks, and cleaning crew. Black women were not allowed in the Navy until 1945. Even then, only four African American women served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. These were among a maximum quota of 48 African American nurses allowed in all of the U.S. military during the war.

The Marine Corps allowed recruitment of African Americans beginning in June 1942. At first, they received segregated training and served in all-black units, though battalions would integrate by the end of World War II. Nearly 8,000 black Marines served in the Pacific Theater, performing particularly well at the Battle of Saipan (September 1944). After the war, the Marine Corps scaled back, resulting in 2,000 remaining African Americans in the service.

During World War II, over 2.5 million African Americans registered for the draft and many volunteered, serving prominently in segregated units within the Army and Army Air Corps. Notable among these were the Buffalo Soldiers, 93rd Infantry Division, 761st Tank Battalion, 452nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion, and 332nd Fighter Group (Tuskegee Airmen). In addition, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion became the first entirely African-American female unit deployed overseas.

By the end of World War II, 992 black pilots had been trained for duty and more than one million African Americans had served in the U.S. Army and Women’s Army Corps. None would receive the Medal of Honor until 1992, when President Bill Clinton honored seven men with the award, all but one of them posthumously.

In late 1945, in response to a study of race policies in the Army, the federal government’s Gillem Board made eighteen recommendations for improving the treatment of black soldiers. Although both the Army and the Navy announced policies of integration and equal rights in early 1946, and the War Department directed the services to adopt such policies in May, elements within every service resisted integration, leading to a sharp decline in African-American enlistment.

In response to racial unrest erupting across the country in 1946, President Harry S. Truman formed a committee to study the problem. In 1947, the Army replaced segregated training programs with integrated courses. The next year, Lt. John E. Rudder became the first African American commissioned officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. When Congress received the final directive from the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, it refused to act on recommendations to integrate the military. In response, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, directing equal treatment for black service members.

Despite Truman’s Executive Order, military leaders largely refused to adopt the new policies. It was not until April 1949, that the services made progress toward integration and equal rights within the military. The impetus came from Defense Secretary Louis Johnson, who directed the services to adopt Truman’s order as official military policy. In response, the Air Force issued a “bill of rights” for black servicemen, the Navy moved to integrate and expand recruitment of African American sailors, and the Marine Corps ended segregation in training.

While the transition from segregation in the military proceeded gradually, integrated units in the Army, Air Force, and Marines were present and fought valiantly during the Korean conflict, with two African American soldiers receiving the Medal of Honor. As a result of rising acceptance and active recruitment, the number of black Marines grew from 1,525 in 1949 to 17,000 in 1953. In 1954, the Army became the last service to fully integrate upon deactivation of the 94th Engineer Battalion.

Though discrimination certainly persisted within the services, the Vietnam War was the first conflict in which white and black soldiers were fully integrated. In addition, the selective use of conscription during the conflict led to a significant rise in African American draftees. In 1967, African Americans made up 11% of the population, but were more than 16% of those who served. This was in spite of the fact that only 29% of Black conscripts were approved for service, compared to 63% of white conscripts. In all, 300,000 African Americans served in Vietnam.

Today, the proportion of African American servicemen and women in the Air Force (15%), Army (21%), and Navy (17%) eclipse that of the general population (13.4%), with only the Marine Corps (10%) falling below the average. Among these, more than 13% are commissioned officers who graduated from a service academy, and nearly 17% hold doctorates, speaking to the tremendous progress made over the course of the two- century journey toward racial integration in the U.S. military.

Social Sharing