Starting from the earliest days of the Radio Laboratories at what would become Fort Monmouth, the community from which the U.S. Army Communications-Electronics Command developed allowed opportunities for people beyond the norms of the time. Women served a visible role as support staff in offices across Camp Little Silver and the Radio Laboratories during the end of World War I, as demonstrated in a series of photographs from 1918.

Prior to and during World War II, there were opportunities for skilled workers and scientists, in both civilian and military roles, regardless of race or gender. Beginning in the 1940s, Fort Monmouth and its satellite of Camp Evans and the U.S. Army Signal Corps Radar Laboratory located there, became a center of Black scientists and engineers. Well known is Dr. Walter McAfee, who began his career at Fort Monmouth in 1942 as a physicist, and contributed the mathematical calculations that made Project Diana possible. But there were many others who made significant contributions. As written in the history by former Electronic Research and Development Command

SES Thomas E. Daniels in 1983, entitled Contributions of Black Americans to Electronic Research, Development, Production Distribution and Training at Fort Monmouth 1940-1982, “… the period 1940-1942 saw approximately 20 black male engineers and physicists arriving and immediately being assigned work in communications, radar, sound ranging, electron tubes, components and countermeasures.” Some of the early Black pioneers in electronic engineering were William (Bill) Gould, William (Bill) Jones and James P. “J.P” Scott. Bill Gould and Bill Jones held the highest ranks during the early 1940's as section chiefs. Their careers began at Fort Hancock where the radar research and development was taking place while the Evans Area was being developed. Others included Harold Tate, who was subsequently to be one of two Black men commissioned as officers, sent to Harvard and MIT, and reassigned to the laboratories, and Thomas Baldwin, a physicist was assigned to a submarine detection group in late 1941. Mr. Tate would go on to lead the group that conceived, designed, and built the first portable radar “gun” in 1962 at the Signal Laboratory’s Advanced Radar Development Branch. In the 1942-1943 time frame, five Black technicians were trained in the installation, operation and maintenance of the SCR-270 and SCR-271 early warning surveillance radars. These radars were used to detect aircraft and for air defense. This team consisting of James Harris, Richard Nixon, Charles Henry, James Roach, and Joseph Gomillion installed these radars at Montauk Point, Long Island, New York; North Truro, Massachusetts; and Chatham, Massachusetts.

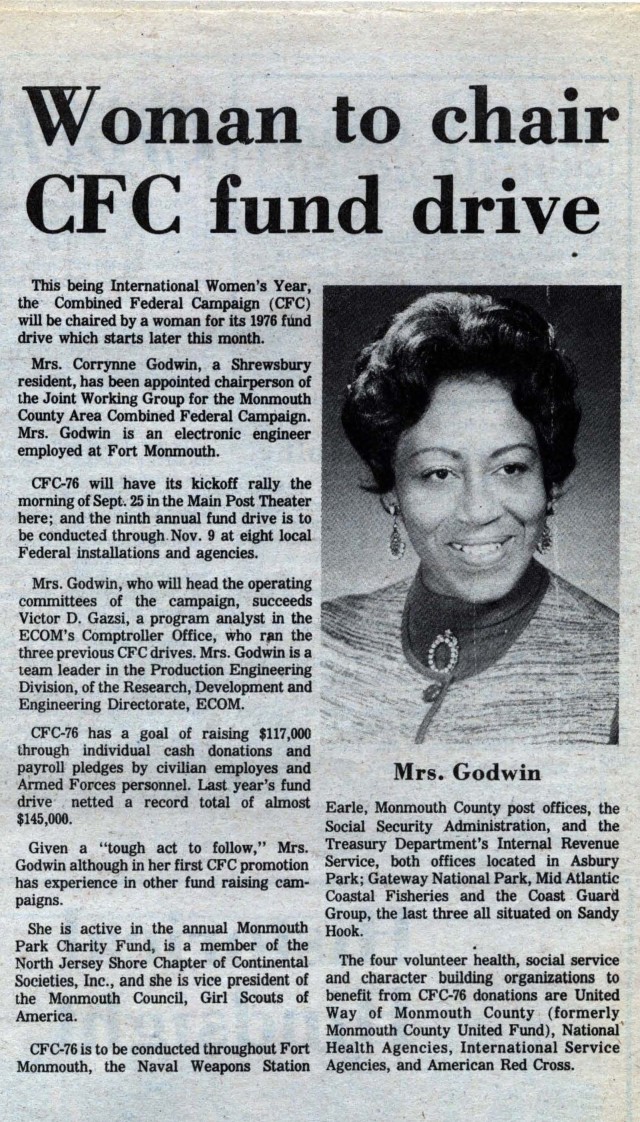

Black women were trained in technical drafting, and found work, too, supporting the different laboratories to prepare layouts for publications, wiring schematics, charts and graphs for engineering reports and technical manuals. The war presented opportunities for college-educated Black women to find technical jobs, a difficult feat at the time. The shortage of men in 1942 allowed Corrynne Godwin and Muriel Robinson Baldwin and two others graduates of Brooklyn College to be hired as Junior Professional Assistants. Corrynne Godwin was later to be one of the first two Back women electronic engineers at Fort Monmouth to attain the senior engineer designation. Ms. Godwin also served as an officer with the Molly Pitcher Toastmistress club, and provided training and support to other women at Fort Monmouth. Corleza Holiman, the other Black woman electronic engineer to reach the senior engineer level, started in 1943 in the engineers in training program. She became an electronic engineer in 1947 as a result of that program. Helen Harris was hired as a chemist in 1942 but left during the reduction in force of 1946. Enid Gittens and Connie Gray from Hunter College were hired in the professional area.

It was also during this time period that the first contingent of Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps soldiers arrived in 1943, initially with the 15th Signal Training Regiment, meant to relieve men for field jobs during World War II. Even before the development of the WAAC program, the Signal Corps had been training women in technical work, including the installation, maintenance and operation of

radio equipment in Signal Corps Repair Shops and Maintenance Depots. Approximately 8,000 civilian women were taught as radio operators, technicians and repair persons, telephone switchboard and instrument repair persons, in early 1943, at various schools and colleges across the Nation.

Acceptance wasn’t universal, and these pioneers faced many hardships and prejudices both within and outside of the workplace. But their enduring contributions, many with decades-long careers dedicated to public service, laid the foundation for a history of inclusion and diversity within the CECOM workplace.

Social Sharing