The U.S. military brings people together from nearly every corner of the world who want to be part of America and what she stands for. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have long served with distinction in all branches of the military service.

Byron Nakagawa’s father served in the U.S. Army during World War II, even though his family was sent to an internment camp in northern California. Two of his dad’s brothers served in the Army during World War II, four during the Korean War, and one was in the Navy.

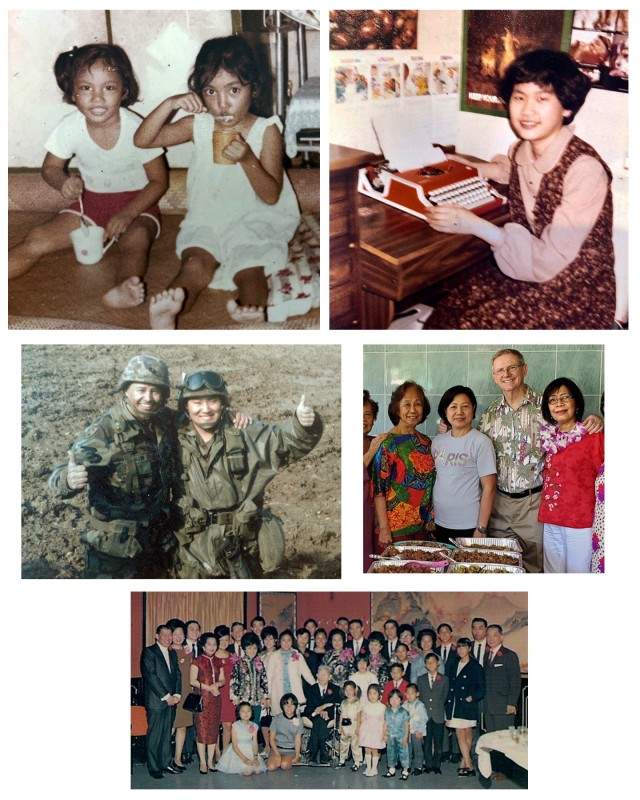

“Family has always been important,” said Nakagawa, a supply tech in the Property Book Office of the Fort Hunter Liggett, Logistics Readiness Center. “My fondest memories were of family reunions and get-togethers.”

He said he learned certain Japanese phrases to speak to his grandparents, who immigrated to America, but has never been to Japan. He missed a chance to accompany his parents there for their 25th wedding anniversary because he had to report to Fort Lewis for ROTC training.

“The military (now) is lot more merit based,” said Nakagawa. It took the end of World War II to prove that “a Soldier’s a Soldier” and units were no longer segregated on the basis of race or ethnicity. “I’ve served in the military. I vote. I try to be a good citizen.”

He also referenced the term “Seki-nin” which roughly means “responsibility and duty.”

“Your responsibility is to the family, the people I serve and work with,” he said. “You’re responsible for your actions, responsible as a leader to your subordinates.”

Annelle "Nelly" Smith, Management Assistant for the Qualified Recycling Program of the DFMWR, grew up in the Philippines and moved to the U.S. in 2009. She echoes the importance of strong family ties in her culture.

“We welcome everyone in our homes, may they be strangers or friends,” she said. “Everyone is called ‘Auntie’ and ‘Uncle.’”

Smith said some of her fondest memories are of traveling to the family’s ancestral home in the province of Pangasinan, and of her grandfather taking her to help in the rice fields or mango orchard. “The feeling of being on top of the world while at the very top of a mango tree was exhilarating as a young girl,” she said. “The singing, joking around while everyone is happily working despite the heat and humidity will be forever etched in my mind.”

The conversations with her grandfather were also memorable. “He explained to me that, despite our background as landowners, not everything should be handed to me and that if I want something, I will have to work for it. He has instilled in me the value of hard work and to never be ashamed of rolling up your sleeves and getting dirty.”

Smith, her parents, and her daughter (a Soldier serving in Landstuhl, Germany) speak a local dialect called Pangasinense. There are 182 native languages and dialects in the Philippines with Tagalog being the official language. Tagalog has been blended with Spanish, for more than three centuries and most people from the Philippines learn to speak English as well.

She said she sees no discrimination against people of color in the Army. Asians and Pacific Islanders “are dedicated professionals who want to protect the country that gave them a home.”

Her parents instilled Filipino values which she tries to pass down to her daughter. “Hospitable, loving, loyal, dedicated and most of all, hard-working. We always have a happy disposition in life and that no matter what life throws at us, we always put a smile on our faces and bravely face it.”

Natividad “Naty” Littlefield, Director of Resource Management, is also from the Philippines and was raised on the island of Luzon. “The typical village, or barrio, I grew up in was characterized by strong family values and faith in God,” she said. Her parents taught her a strong work ethic and values. “They taught me to believe and trust God, to respect our elders, to work hard, and to be humble. I learned to overcome life’s challenges through these values.”

Littlefield and her siblings worked on the farm planting rice, tobacco and corn, and tending the cattle and water buffalos that tilled the fields. Her parents made sure they received an education so the children didn’t “end up as farmers like them.”

However, she said that now living in a “land of plenty” she appreciates that many Filipinos in the barrio are happy and content with very little. “They get up early every day to work hard in the fields, but in the evening they come home relaxed and happy, and have a good time eating, singing karaoke with neighbors, always surrounded by children.”

She relishes the memories of that simple life, playing with other kids in the rain and swimming in the river. Family gatherings where the adults would cook most of the night and the festivities would last throughout the day are traditions that continue to this day, she said.

Littlefield can converse with her mother in both the Ilocano dialect and English, but her father can only speak Ilocano. She and her family visit regularly and bring gifts (pasalubong) such as clothing, shoes, lotion, Spam, canned goods, coffee, and candy for relatives and neighbors. “It’s a tradition of giving,” she said, “especially if returning from America or abroad.”

Littlefield is retired from the U.S. Army Reserve as an Administrative Specialist and Assistant Inspector General, and has served many years as an Army Civilian. “I see the Army as a model for embracing different ethnicities and cultures,” she said. “This is one of the Army’s defining values and what makes it the strong organization that it has become.”

Although Amy Phillips is “100 percent Chinese,” she says, more than that, she is 100 percent American.

“My biggest peeve is when people ask me about my nationality,” she said. “When I first moved to Hawaii, people used to ask me if I was ‘pure’ when I tell them I’m Chinese. Coming from New York City, I had no idea that it was common in Hawaii to have mixed races.”

A former Army Reserve officer and now the Public Affairs Officer at Fort Hunter Liggett, Phillips says, “I lived in many states while my husband was serving in the Army, and often, I was the lone non-white person.” That’s a contrast to the life she had growing up.

“I may look Chinese and have a slight accent, but I really don’t know that much about my cultural background, having moved around since I was two years old,” said Phillips. “I was born in Hong Kong when it was still a British colony – my first passport was red for English citizens. We moved to Holland, and then to New York City in 1976. I grew up mostly in a Chinese community. Chinese kids were the majority in my grade school.”

Her immigrant family members all worked in the garment industry, which had mostly Chinese workers at that time. “I spent my childhood in factories,” said Phillips. “I’d do homework in the dark, narrow and mice-infested hallways and stairs. I took naps in the cloth bins and used the floor-to ceiling clothing racks as my jungle gym. I got yelled at a lot, of course.”

She and her siblings converse with their mother in Chinese, and she can cook Chinese food “with a recipe.” She has also visited Hong Kong several times and loves the shopping options and fashions. She also visited mainland China as a teenager but didn’t enjoy it because the rural village they visited only had smelly public outhouses. “I had this experience, too, during boot camp,” she said wryly.

Phillips pointed out that the myth of Chinese being math wizards isn’t true. “I am a prime example,” joked the wordsmith. She believes the most distinct characteristic of Chinese people is that they are hard workers.

She has fond memories of celebrating the mid-autumn festival with family, running around in the streets with little lighted lanterns, and of going to Chinatown in New York City to see the lion dances and fireworks. Phillips appreciates the Army’s ethnic observances.

“I think it’s important for people to learn about different cultures, to better understand each other.” However, she makes one thing clear. “I’m an American, and that’s that.”

Kathy Ng’s father is what she calls a “paper son.” That’s what a Chinese immigrant was called if he faked his papers to pretend to be someone’s son, and her father said he was the son of the man who was actually his older brother. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited most immigration and he had be convincing under interrogation that he was who he said. However, the lie was discovered and he was imprisoned as an illegal alien.

“He was later able to gain citizenship by enlisting in the Army Air Force in WWII,” said Ng, who is the Deputy Director and a Contracting Officer's Representative at the Network Enterprise Center. Both of her parents were from Canton province. “When my mother was 11, the family fled China to escape the Japanese invasion,” she said. “My grandmother died in childbirth and my mother had to care for her siblings. My father passed when I was three so my mother had to raise four of us as a single parent. My siblings and I were the first ones to have college degrees in our family and we all have children who are doing well.”

Her fondest memories are of family and tradition, both of which are strong in Chinese culture. “We visited my aunts and uncles often and played with my cousins. We celebrated all the traditions, and enjoyed the food associated with those traditions. My aunts, mom, elder siblings and cousins would gather in the kitchen and make those foods. Since I was the youngest (I was more the age of their kids), I mostly got to just eat those things.”

She visited her parents’ village in 1998. “The homes are very old and most of the people are very poor,” she reminisced. “We are very lucky to be here in America. Although in the larger metropolitan areas it is more developed and they had modern conveniences.”

Ng said she is thankful for her heritage and for the opportunities offered by the Army the same as anyone. “I am very appreciative of my ancestors and their struggles.”

The Army’s theme for celebrating Asian American, Pacific Islander Heritage Month in May was “Unite our Nation by Empowering Equality.” There are now 28 Asian and 19 Pacific Islander subgroups representing a vast array of languages and cultures currently serving in the U.S. Army.

Social Sharing