Marene Allison wanted to make sure it was real.

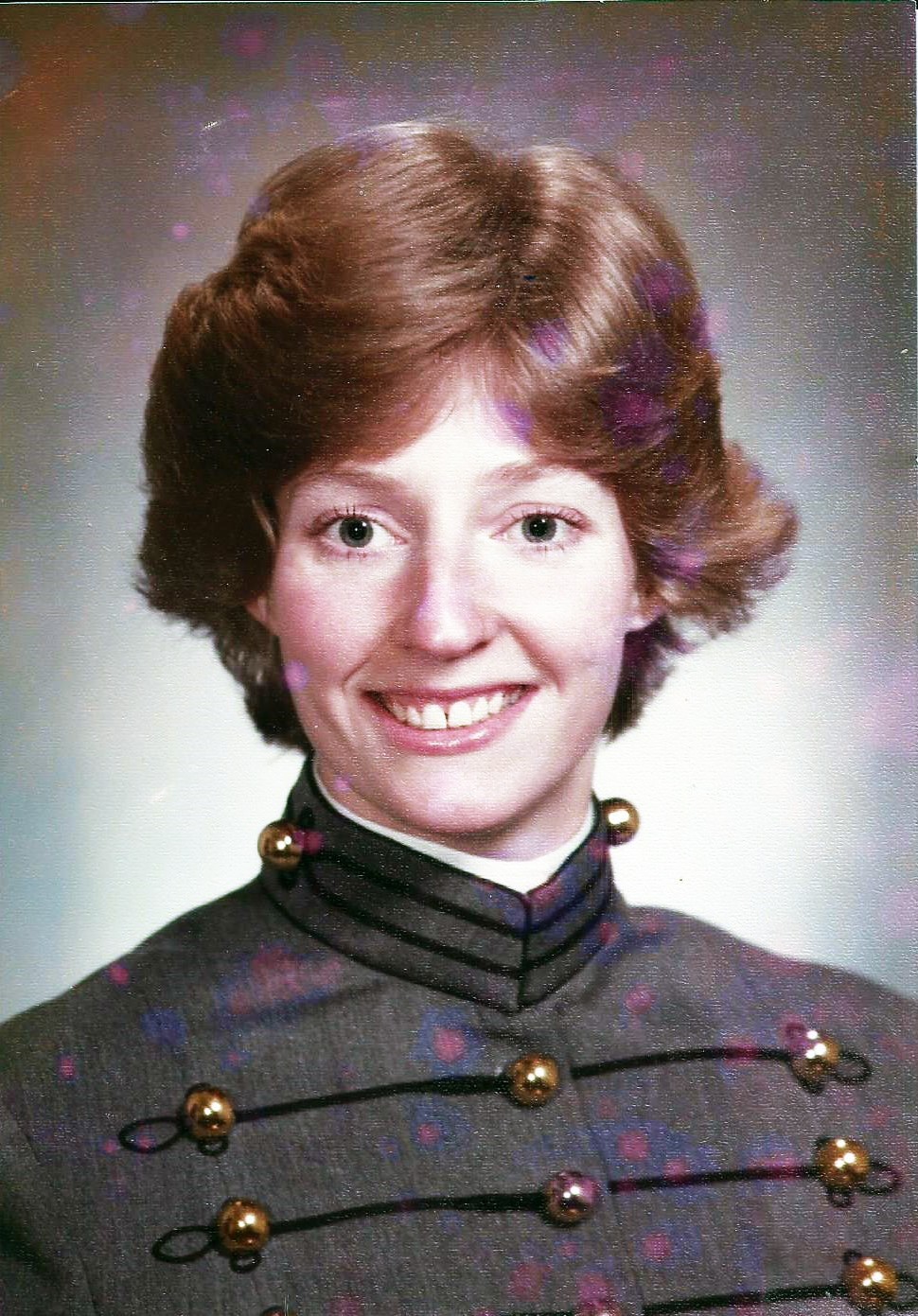

As she stood near the Cadet Chapel with her family, friends and members of her cadet company about a half hour before the Class of 1980’s graduation from the U.S. Military Academy, she had to check. So, she turned to her roommate and asked if this was all real. If they were actually about to graduate, or if it was all a dream and she was going to wake up on Reception Day and have to start the journey all over again.

Forty-seven months earlier, Allison and 118 other women had arrived at a U.S. Military Academy that from all accounts was not ready for them. Bathrooms still had urinals in them after being hastily changed over from men’s to women’s. Uniforms malfunctioned or didn’t fit right as the academy adjusted to a new population, and West Point was led by a superintendent, Lt. Gen. Sidney B. Berry, who originally resisted the arrival of females.

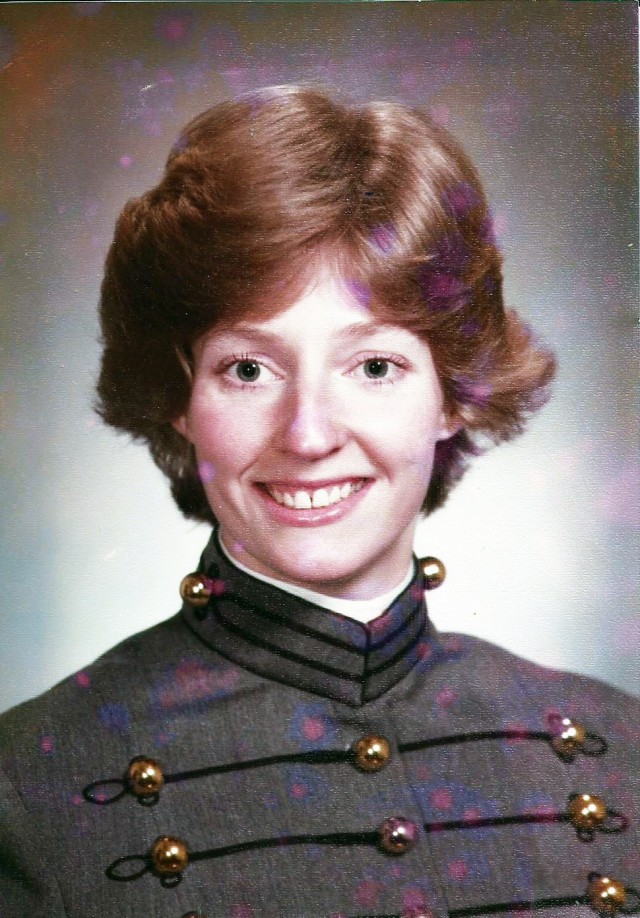

On Reception Day July 7, 1976, the women in the Class of 1980 had opened the doors to the academy as the first women to be admitted. Now, on a sunny day in May 1980, it was time for the 62 women, out of the 119 who originally arrived on R-Day, who had made it to graduation to break through the glass ceiling, even if that meant, as Allison said while reflecting back on the day 40 years later, “there's some shards of glass that may have been embedded in my shoulder now and then.”

There had been good times and bad during the women’s four years at the academy. Those shards of glass reflected the hazing they had been subjected to by some members of the Corps of Cadets. It represented the extra scrutiny they had faced as the first women to walk the halls of West Point.

The pieces embedded deepest of all were the scars left behind by the assaults and harassment some members of the class had been subjected to by male cadets who didn’t feel women should be admitted to the academy.

Through all the challenges, they had proved to themselves and the corps—which now in May 1980 had women in every class and company for the first time—that they belonged.

The first cadet graduated from West Point in 1802 and in the 178 years since, nearly 35,000 men had joined the Long Gray Line of academy graduates. Their names tell the story of America during those nearly two centuries. Grant, Lee, Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton and Aldrin all had donned the cadet gray before their Army careers.

Now, it was time for them to be joined by Andrea Hollen, Sue Fulton, Marene Nyberg, Pat Walker and 58 other women who were making their own kind of history, because as Nyberg-Allison’s roommate undoubtedly assured her on the bright sunny May day right before they walked to Michie Stadium, them graduating was not a dream.

Duty, Honor, Country

On July 7, 1976, the U.S. Military Academy welcomed 1,452 new cadets on Reception Day. Nine months to the day earlier, President Gerald Ford signed Public Law 94-106 allowing women to be admitted to the U.S. Military, Naval and Air Force Academies for the first time.

Nearly 45 years later, Nancy Gucwa can still remember the moment she first heard the news and West Point became a possibility. She was sitting at her home on Staten Island doing homework when her dad saw the announcement on the news that Ford had opened the academies to women and came to ask her what she thought. Her dad had served in the Navy during World War II, but until that moment Gucwa’s plans didn’t include serving in the military. Instead, she was considering attending law school.

She’d heard of West Point as she lived just over an hour south on Staten Island, but knew little of the academy. After hearing the news, she requested information about it and her plans quickly changed.

The brochure told her about the academy’s motto of Duty, Honor, Country. It listed famous graduates such as Douglas MacArthur, Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar Bradley. And it promised to not just provide her an education, but to develop her into a leader of character.

“The duty, honor and country, and just the opportunity to be built into a leader, have character and to serve my country was very appealing,” Gucwa said. “It was out of that desire, as the saying goes, to be all you can be,” that she decided to apply to and ultimately attend West Point.

Nearly five years before she stood in the shadow of the Cadet Chapel and questioned the reality of the moment, Marene Allison would spend Sunday mornings reading the Boston Globe with her dad. From a small, one paragraph brief in the Boston Globe Magazine on one of those Sunday mornings, Allison learned that the service academies would begin admitting women. Her dad served in the Air Force, her brother was drafted into the Navy during the Vietnam War, and three cousins spent a career serving in the Air Force, so service was embedded in her family.

She made the decision to apply to an academy, but it was not West Point she planned to attend. It was the Air Force Academy. She put together her application and then worked to secure a nomination from a senator or representative in her home state of Massachusetts. She remembers her application being nicely typed out, but the response she got back was not.

“A few weeks after I applied, I got kind of this ruffled piece of paper from Sen. (Ted) Kennedy’s office that I guess an intern must have stuck in an envelope. It wasn't even typed out … that basically said, Sen. Kennedy didn't think I was qualified or whatever for the nomination,” Allison recalled.

Then, a couple weeks later, Allison got a letter from Congresswoman Margaret Heckler’s office informing her that Heckler had chosen Allison to receive her principal nomination. But it wasn’t to the Air Force Academy. It was to West Point.

So, Allison hastily filled out an application and arrived at West Point for Reception Day having never seen the academy before.

“I kind of made it the theme of my life. When somebody gives me lemons make lemonade,” Allison said.

Although the academies didn’t start admitting women until 1976, the Air Force ROTC program had opened to women in 1970 and then the Army and Navy programs followed suit in 1972. As the service academies were not yet accepting women, Sue Fulton’s plan starting her junior year of high school was to attend college on an ROTC scholarship. Her friend had attended the University of Florida as a member of the ROTC program soon after women were allowed to join, and Fulton said she saw it as a good career and also a way to pay for college.

Then, her dad came home and said a friend had told him West Point was going to admit women for the first time. Her focus immediately switched from earning an ROTC scholarship to being admitted to the academy, even though it was a world away from the small town of Jensen Beach, Florida, where she grew up.

She visited the academy for the first time in early 1976 and was able to attend a class and learn more about West Point. When she arrived, there was still snow on the ground, but that wouldn’t deter her from the dream that had crystalized the moment her dad told her West Point was an option.

“The challenge of West Point was so exciting to me; the notion of being challenged at a level that I hadn't imagined,” Fulton said. “I had a very idealistic view about serving my country and so I was stars in my eyes about the opportunity to serve my country in the Army.”

Carol Barkalow had a similar plan and knew exactly what her future held at the age of 16. She was going to graduate from high school, attend college on an ROTC scholarship and after completing her service obligation become a coach. Then, she made the decision to cut through her high school guidance counselor’s office and the entire plan changed.

He stopped her and asked if she had considered applying to West Point as the academy was going to admit women for the first time in its incoming class and he knew she was planning to join the Army through ROTC.

Despite growing up in upstate New York near Saratoga, Barkalow said she didn’t even know where West Point was at the time, but she decided to apply. In the end, the choice was made for her as West Point admitted her as a member of the Class of 1980, and she didn’t receive the ROTC scholarship.

Pat Locke took a different route to the academy than most of her future classmates. She had enlisted in the Army at 17 in order to escape her hometown of Detroit and was stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana, as a communications specialist in a signal battalion.

In early 1976, her battalion commander called her into his office and asked if she wanted to attend West Point. He gave her no time to think about it or weigh her options. Locke had to decide on the spot whether she wanted to stay at Fort Polk or attend West Point.

“I didn't know what it was, or what I would do there or what it was for,” she said, but after the battalion commander told her that if she made it through she would receive a college degree, so she decided to take the risk.

That night, she got in her car and began the drive from Louisiana to New Jersey to enroll at the U.S. Military Academy Preparatory School at Fort Monmouth. The men had started their preparatory school education the previous summer, but at the time the service academies were still closed to women.

After the law changed, female cadet candidates arrived at the prep school in early 1976 and were put on an accelerated program to prepare them to enter West Point in July.

Twenty women started the prep school with Locke, but only six were admitted to the Class of 1980 at the academy including her, she said.

“There was a whole bunch of rancor about that, because they didn't think I should be going because I was like the least qualified of all of them,” Locke said. “Or in their mind, I was the least qualified of all of them, but I think I was probably a better fit than they were.”

Yes sir. No sir. No excuse sir. Sir, I do not understand.

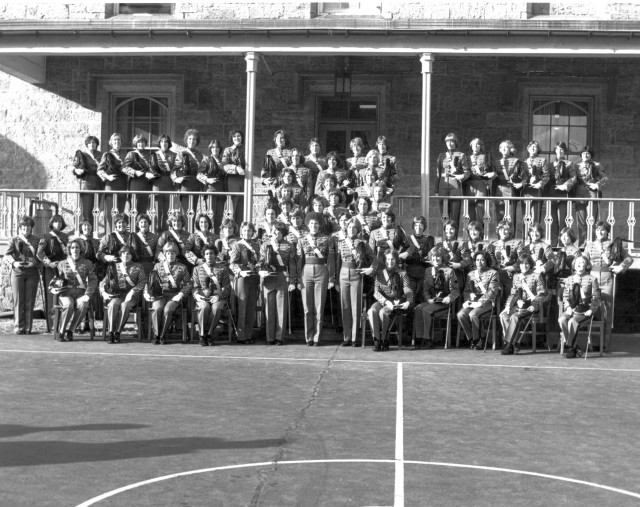

West Point was founded in 1802, but until that July day in 1976 when Gucwa, Allison, Fulton, Barkalow, Locke and 114 other women arrived along the banks of the Hudson River, each of the more than 30,000 cadets to don the gray uniforms that give the Long Gray Line its name had been a man.

They started the day by arriving at Michie Stadium along with their parents, the same place where four years later they would receive their diplomas as graduates of the academy. Fulton said her mother remembers being given 30 seconds to say goodbye and then turning around and her being gone to board a bus and set off on her cadet career.

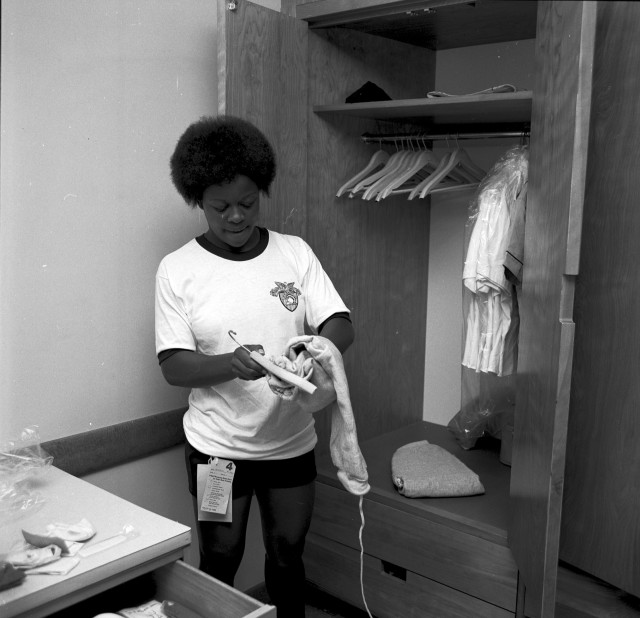

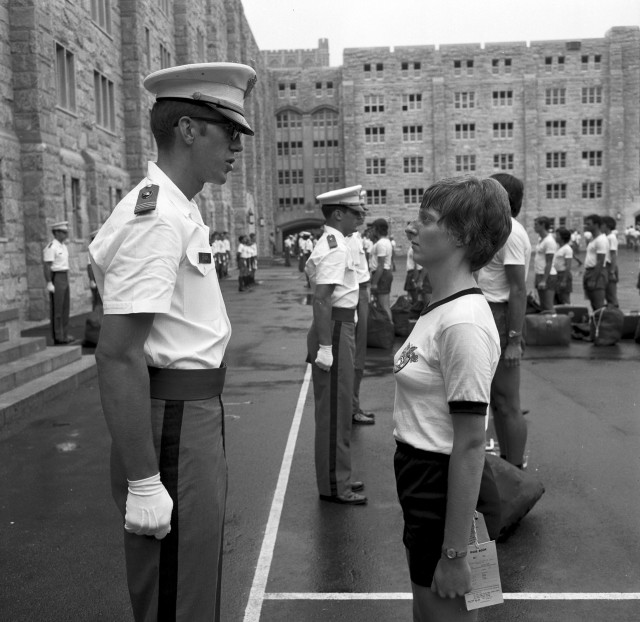

Old photos from the day show women arriving with suitcases in hand in striped or flowery blouses—and even dresses—while being stopped for media interviews as they walked down the steps of the stadium. Then, their civilian clothes were quickly traded out for physical fitness uniforms as they began their cadet careers.

Snapshots show male cadets standing in line shirtless waiting to take a pull-up test as the women stand in their own line wearing what is akin to a single piece bathing suit with shorts over the bottom as they wait to take the test. Then, dressed in white shirts with black cuffs and collars atop black shorts, socks and shoes, the women begin to learn the basics of being a cadet alongside their male classmates.

The women who arrived that day describe it as “chaotic,” “confusing” and “scary” as they learned to march, were screamed and yelled at, reported to the cadet in the red sash and were taught that for the summer—and throughout their plebe year—they were only allowed to respond in one of four ways when spoken to by an upperclass cadet or an officer outside of class—yes sir; no sir; no excuse sir; and sir, I do not understand.

“You learned how to square your corners and basically all the rules and regulations of West Point. It was a lot all at once, but you were in it with all the other plebes,” Gucwa said. “So, it was challenging, but in a crazy way, it was also exciting.”

The academy had tried to prepare between October when Ford signed the law allowing women to enter the academy and July when they arrived with the Class of 1980, but looking back 40 years later the women said it quickly became clear they were stepping into a man’s world that was being hastily adjusted to accommodate them.

Some bathrooms still had urinals in them. Adjustments had been made to the full-dress coats’ tails to accommodate the women, but on their first day at the academy many of the women’s gray uniform pants split open because they had been designed with plastic zippers.

Barkalow said she had to wear her platoon leader’s pants for the oath ceremony parade at the end of the day, while Allison remembers marching across the Plain with the white tails of her shirt sticking out the front of her pants.

“They made some ignorant decisions and I don't know why, or I don't know who made them,” Barkalow said.

But even more than a urinal in the wrong place or a split zipper, it is the memories of the treatment they endured that they still carry as scars. They were hazed throughout that first summer, but it was when the full Corps of Cadets returned in August to begin the academic year that the harassment truly began, many of the women said.

At times, Barkalow said, the women couldn’t tell if they were being hazed simply because they were plebes or if it was because they were women. Other times though, the reason was abundantly clear, she said. They were called names, tortured by both upperclass cadets and officers, and in some cases assaulted by their peers who didn’t feel like women belonged at the academy, the women said.

Allison said it wasn’t until years later while attending a seminar that the women’s standing in the corps was fully explained to her by an African American cadet who had been a cow or a firstie during their plebe year.

“He said that the black males always felt like they didn't belong, and it was only after the females showed up did they feel like they weren't the lowest class at West Point,” Allison said.

The women were a new species at the academy. They were surrounded by men who had never served with women or who were used to attending an academy without them, and were not ready to accept their presence or treat them as equals, Fulton said.

“They couldn't conceive of simply treating us as cadets,” Fulton said. “They could only see us as women cadets, which was clearly a completely different species than a cadet. There were cadets and there were women cadets. And the words for women cadets typically were a lot less socially acceptable than women cadets.”

Gucwa can still vividly tell the story of the day she was standing in the hallway announcing the minutes until dinner, when five upperclass cadets not even from her company began to harass her. They surrounded her and began to yell that they “recognized her ugly face” from a TV interview and taunted her with the proclamation that “you’re not going to last if I can help it.”

Staring at the clock on the wall, she called out the five-minute bell and then the two-minute bell, until it was time for dinner and the harassment subsided. From start to finish, it lasted maybe eight minutes, she said, but the moment has never left her.

When walking past upperclass cadets and officers, the plebes were required to say good morning, sir; or good, afternoon, sir. Gucwa said it was not uncommon for the male cadets to respond, “It was a good morning until you fill in the blank got here and they would use a crude word. That was daily. That was multiple times a day, but it still hurt. It still stung.”

For Locke, it isn’t so much individual moments of harassment that stand out to her, although there were instances of “terrible” treatment. She was used to harsh treatment from her upbringing and then her time in the Army. The hazing and the harassment she could endure, although with more than 40 years of separation she will slyly mention the fights she got into when no one was watching. It was the isolation she felt at the academy, especially during that first year, and the academics that threatened to be her undoing.

She had been raised in the inner city of Detroit and arrived at the academy as one of only two African American females amidst a sea of more than 4,000 cadets. She spoke differently than other cadets. Her culture and background were different, and as the other women in her class confided in each other and banded together to make it through, she said she felt like she was largely on her own.

She found solace in the music of the Hellcats, who would play the drums and bugles in the morning and during drills. It harkened her back to her days as a majorette and gave her a sense of normalcy in an unfamiliar world.

She finally found a community by joining the women’s gymnastics team during her yearling year and overcame her academic challenges by learning how to learn.

“I was singularly focused on not flunking out,” Locke said. “So, a lot of everything else that they did or what happened, it just kind of rolled off of me because I had to really stay focused on what I was trying to do. I guess the bottom line is I was kind of used to abuse so it bothered me less than losing the opportunity to get a degree.”

Barkalow, too, found her acceptance at the academy through sports as she played on West Point’s inaugural women’s basketball team. Although practices would make her arrive late for dinner and caused her to be an easy target for harassment as she sat in the nearly empty mess hall, it was also through her and her teammates’ performances on the court that she felt they began to change some men’s minds about whether they deserved to be at the academy. But even with the increased acceptance she found as an athlete, there was still a moment during her plebe year when she almost called it quits.

During the spring semester, she walked into her squad leader’s office and told him she was quitting as she’d had enough of the treatment. Instead of simply letting her quit, he made her go back to her room and write down the reasons she wanted to leave, followed by the reasons she wanted to stay.

So, on the front of a piece of paper she began to list the reasons to leave. Then she flipped over the sheet and thought about why she should stay. Although the second list was shorter, it proved to carry more weight.

“It kept coming back to I want to serve my country and I believed that this place was the best place to prepare me to do that,” Barkalow said. “He taught me a valuable lesson that maybe there were a lot of reasons to leave, but the reasons to stay truly outweighed those reasons to leave.”

Despite the harsh treatment they at times endured and the moments they thought about quitting, each of the women said they’d go through their West Point experience again because of the positive impact it had on their lives.

The treatment for many of the women improved after their plebe year, they said, but the start of a new year came with its own set of challenges. As more women were admitted in the Class of 1981, the current and new female cadets were spread throughout the corps so for the first time every company would have women in it. For many of the Class of 1980 women, that meant they were moved to a different company and had to assimilate to new male classmates and upperclassmen who had spent the previous year in male-only companies.

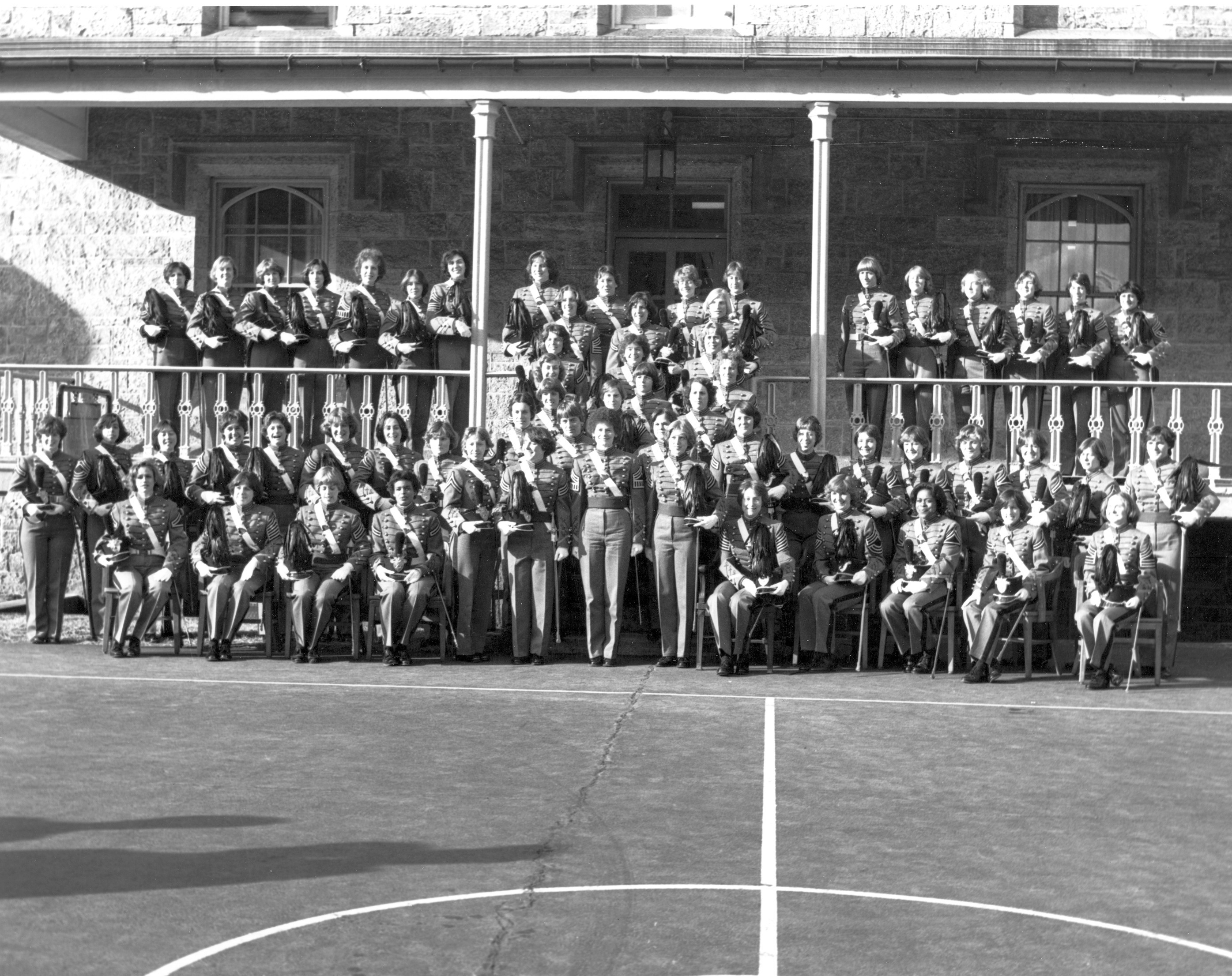

While there were challenging times of harassment or hazing, Fulton says she also has fond memories of the shenanigans they would get into right alongside the male cadets. And through the ups and downs of their 47 months at the academy, on May 28, 1980, 62 women stood ready to join the Long Gray Line and add their names to the list of graduates from West Point.

“The happiest day of my life”

Allison said she remembers the warmth of the day as they returned to Michie Stadium where they had said goodbye to their families on R-Day, boarded a bus and left their old lives behind. On R-Day, 1,484 men and women had arrived at the academy as wide-eyed new cadets ready to take on the challenges of West Point. On graduation day, 870 of them were commissioned as second lieutenants in the Army.

Secretary of Defense Harold Brown served as the commencement speaker and spoke to the class about the challenges they would face as they began their Army careers, as America and the Soviet Union were still locked in the Cold War.

He spoke of the challenges that remained in both Korea and Vietnam, where the U.S. had recently fought wars, and reminded the class they were entering the Army at a critical time in American history as they’d be the leaders who would usher in the 21st century.

“Every West Point commencement is an historic occasion,” Brown said during his speech. “This one, with 62 women graduates, takes on a special significance. Every member of this class is to be congratulated for a job well done. You should be proud of the history you have made these past four years. I take special pride in addressing this graduating class.”

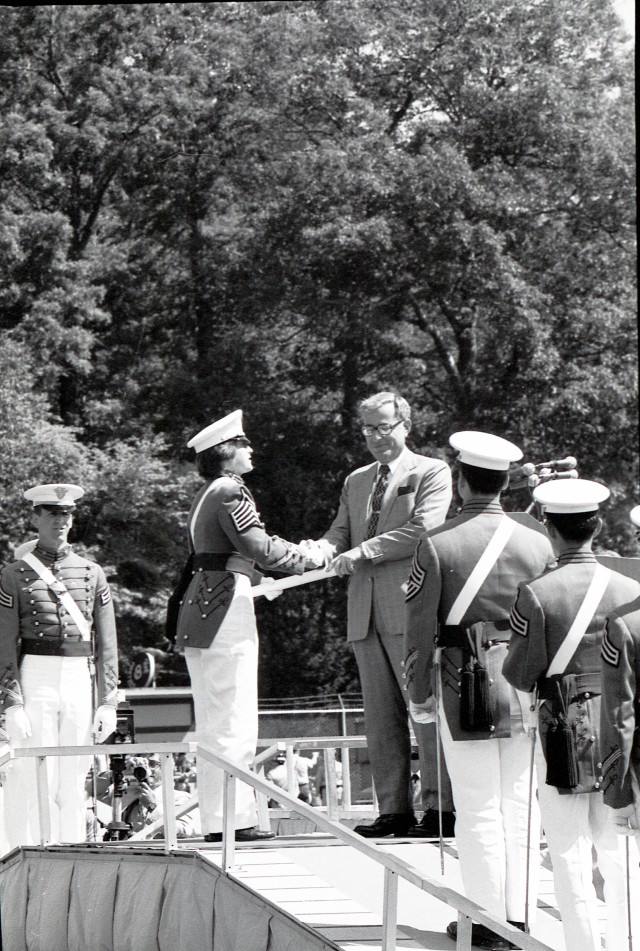

Prior to that May day, nearly 35,000 men had graduated from the academy. As the top-ranked woman in the class, Andrea Hollen —who was also a Rhodes Scholar that year —became the first woman to receive a West Point diploma and become a member of the Long Gray Line.

She was followed by Allison, Barkalow, Gucwa, Fulton, Locke and the 56 other women in the Class of 1980 who made history together.

“When I got my hand on my diploma, I have to tell you it was the happiest day of my life,” Barkalow said. “I was like, 'You know what? No one can take this away from me.' It had been a long four years. It was the best thing that'd happened to me in my life to that point.”

Barkalow branched Air Defense Artillery and started her career in Germany before changing her branch to transportation. She spent 22 years in the Army and retired in 2002.

Her dream as a 16-year-old in high school had been to be a coach, and while she never roamed the sidelines of a court or field with a clipboard in hand, she said she found throughout her career that being an officer and leading troops fulfilled the dream she had, albeit in a different way.

“If I was 17, I would do it again, because I think the things that I learned without even knowing I learned them and the positions I've been in helped create for me a positive successful career in doing what I wanted to do,” she said.

Allison joined the military police after graduation from West Point and began her career at Fort Hood, Texas. She served for six years before getting out of the Army, along with her husband, and they both became agents with the FBI, because the “Secretary of the Army and Secretary of Defense didn't want women to get shot at.”

She is currently the Vice President and Chief Information Security Officer for Johnson & Johnson.

“It was the people that gave us a smile. It was the people who said, 'Yes, they can do it,' that got us through,” Allison said. “Then the next group was able to come after. Now with over 5,200 women, 44 women Rangers, women who are competing in Sapper skill and women who are proving what they can do, that's why it was done and that's why it was good for America.”

Locke had served in a signal battalion before attending West Point but chose to branch Air Defense Artillery after graduation. She resumed her Army career at Fort Bliss, Texas, and retired from active duty in 1995 as a major. After retirement, she founded the Seeds of Humanity Foundation to help underserved communities throughout the country.

As part of her work, she has strived to improve the diversity of West Point by working with West Point admissions and the academy’s diversity office to host Leadership, Ethics and Diversity in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math seminars throughout the country.

“It's never going to be easy, and it's not supposed to be easy when you're gaining skills, gaining competence, gaining character and becoming a leader,” Locke said. “It's not supposed to be easy. I would make the same decision again, and I truly wouldn't want it to be easier than it was.”

Gucwa began her career in the Quartermasters branch at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. She then served a tour in Germany before leaving active duty for the reserves and joining the corporate world. As her career progressed, she eventually left the reserves before beginning the process of rejoining following 9/11. She served her second stint in the reserves from 2003-08 before retiring as a lieutenant colonel.

Gucwa left the corporate world in 2006 and joined the Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration at their monastery in Missouri where she is now known as Sister Nancy Rose Gucwa.

“I would do it again, most definitely,” Gucwa said. “Being in that first class was both challenging and rewarding. The Army has greatly benefited from the contributions of West Point women graduates, and I'm proud I played a part in making that happen.”

Fulton commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Signal Corps and also began her career in Germany. She served for eight years before leaving active duty in 1986 because she was not allowed to serve as an openly gay woman under don’t ask, don’t tell.

She has spent the years since leaving the military working in brand management for companies such as Procter & Gamble. She also actively fought against the law that shortened her own Army career by helping to found Knights Out, an LGBTQ alumni group, before serving on the academy’s board of visitors from 2011 to December 2019.

“I think possibly the biggest impact on me personally was learning that I was capable of so much more than I thought was possible,” Fulton said. “There are so many particularly physical and military challenges I had no idea I would be capable of, but with enough heart and enough work I succeeded.”

On June 13, the Class of 2020 will become the 40th graduating class to include women. In that time, more than 5,000 women have graduated, and they have gone on to become generals and corporate leaders.

They have earned the Ranger tab and flown to the International Space Station. Women have led the corps as cadets and served as senior leaders at the academy.

It has become a popular refrain among women from the inaugural class that West Point is built upon years of “tradition unmarred by progress,” but on that July day in 1976 when they donned the cadet gray for the first time the women in the Class of 1980 began the process of proving that not only did women belong at the academy, but that they could succeed there and beyond.

“My graduation day was so profoundly moving, bittersweet and just so incredibly emotional, that I couldn't even think about it for years, because it would take my breath away,” Fulton said. “I just couldn't even relive that moment. I had to attend five or six graduations before I got over that, and just being overwhelmed with emotion, because of that feeling from that day on May 28, 1980. Knowing that I had done things I never thought I was capable of, but probably more than that was a distant awareness that we had changed the world.”

(Editor’s note: This is the first in a three-part series. Part two next week will highlight important women to graduate since 1980.)

Social Sharing