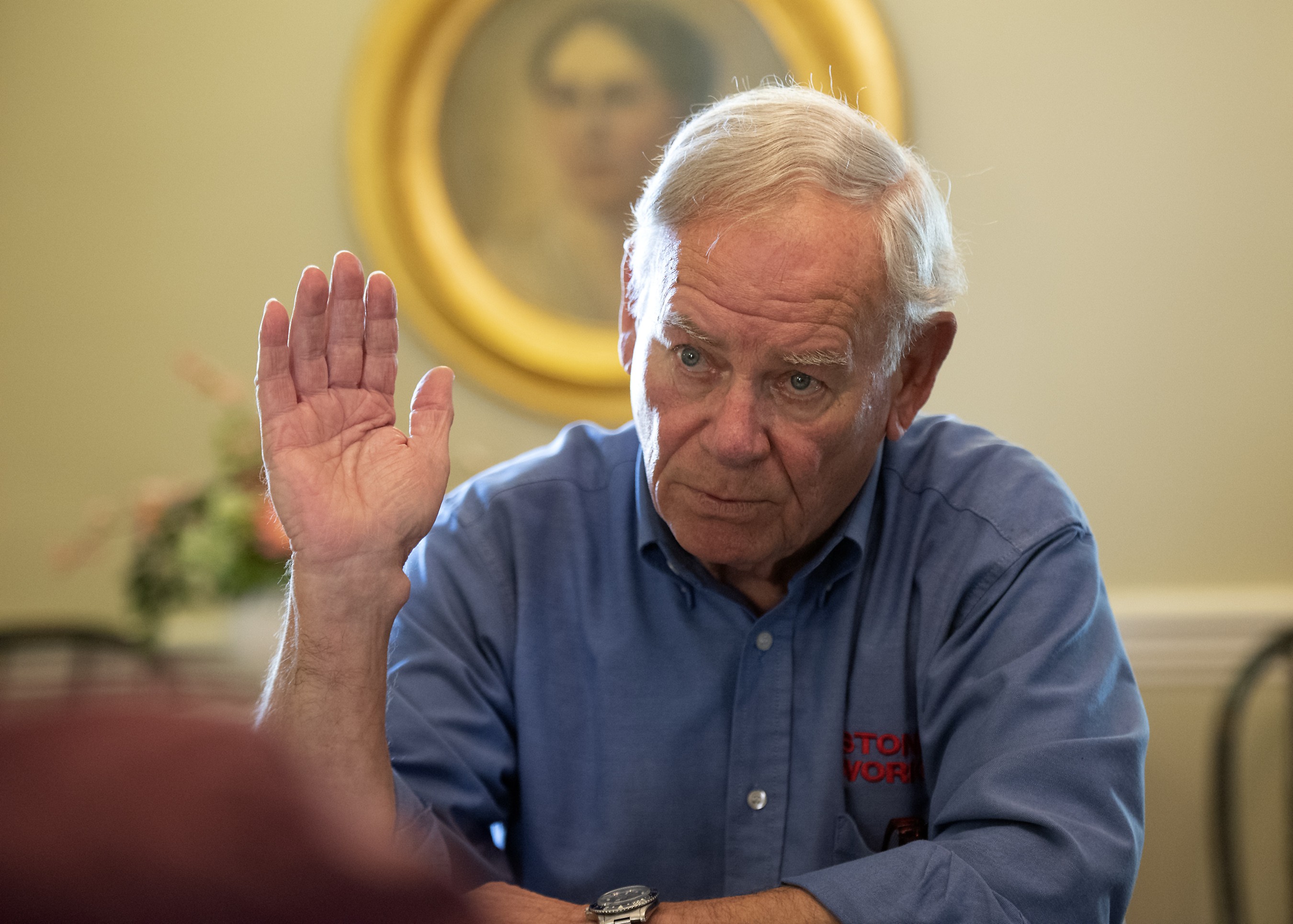

These days, Morris Miller keeps himself busy maintaining the Brown-Pusey House in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. As a former local businessman and current chairman of the board that runs affairs at the historic house, Miller knows the importance of preserving the past.

Take the history of Fort Knox's Armored Force Medical Research Laboratory. At the 77th anniversary of the laboratory's start, Miller recalled his time there.

A week after Miller's birth in 1942, the U.S. Army's Armored Force stood up the lab at the installation in the midst of World War II. The purpose was to "study the human equation in … armor and vehicles used by armored forces," said Col. Albert Kenner, AMRL's first surgeon and commander, a year after he was appointed to create the lab, as quoted in Making Tanks Safe: Armored Force Medical Research Laboratory, by Dr. Sanders Marble "I thought that a tank might be likened to [an] occupational hazard and studied it from that standpoint. The tanks originally had been built without reference to the crews."

For Miller, commonly known by his friends as "Mo," it would be several years before he found himself working there. He acknowledged how his birth coincided with the research lab's founding.

"I guess it had my blessing from the start," Miller said.

In the early years, the laboratory had a threefold mission, according to Marble: "Identify the sources and evaluate the magnitude of the stresses imposed upon the tank crew and other weapon operators; determine the anatomical, biomechanical, physiological and psychological limits of the [assumed healthy] men selected as Soldiers -- what would make them unfit to fight; and, find the balance between operating demands and human capabilities to avoid Soldier breakdown and/or weapon failure."

Those stresses included the now-famous extreme cold and hot temperature tests, but also included several other test areas: toxic gases in armored vehicles, crew-fatigue research, vision in tanks, and night vision from tanks.

By 1962, when Miller was a 20-year-old college student, AMRL had expanded testing to other areas as the need arose. One such area was the study of poisonous snake bite effects from different countries where Soldiers conducted operations to devise antitoxins that would save Soldiers' lives.

"I knew about the jobs; my father worked for Personnel at Fort Knox at the time," said Miller. "I had had a job the year before delivering beer and food and supplies to all of the clubs there."

Miller decided he wanted to take two years off from college to work at the laboratory, so he applied for a job. The snake testing area showed an interest in him.

"I was interviewed by a Dr. [Charles] Goucher, and he was a super guy. He was very interested in reptiles and that whole process," said Miller. "When I was hired, the idea was that I would be the technician that would do several different jobs."

Miller recalled working not only with Goucher, but also with a Capt. Herschel Flowers, who would come in from time to time to extract venom and help Goucher run the tests. Other than Goucher, Miller ended up being the only civilian in the group.

"Once we thought we had found something that would work to offset the venom, we would have quartz cuvettes that we put various amounts and types of venom into to test the reactions. We would then clean the cuvettes and conduct the tests again and again," said Miller. "The snakes that we had there were primarily -- water moccasins -- cottonmouths."

Miller said while he didn't remember Flowers milking cobras at the facility, he did see Flowers conduct what Miller called a trick with them.

"Flowers would put his hand up in front of the cobra. The cobra could strike no farther than the height he could rise. If it was 18 inches, that was it, and Flowers would be at 19 inches away," said Miller. "We all thought he was the bravest man alive."

Miller remembered the team testing other snakes as well, like the coral snake. In one test, a Soldier named Dalrymple was struck by a snake while trying to hold the snake for Flowers to milk the venom. He said Dalrymple had to be quickly injected by the anti-venom they had been testing and then admitted to the hospital. He lived.

This was a significant result for the team, according to Miller, because prior to it, they had conducted all their tests on rabbits and chimpanzees.

Miller went back to college after 1963 and then signed up to join the Peace Corps after graduating in 1965. Life would take him away from the area, and then back to take care of his sick mother. Miller ended up staying here, but he always remembered his time at AMRL.

"In terms of a contribution, to me that time at AMRL was a significant contribution," said Miller. "I would have done something like that again if I'd had the opportunity.

"It might not have been snakes, and it certainly wouldn't have been hot or cold weather -- I'd of picked out something easy; maybe golf if they had it."

Social Sharing