FORT MEADE, Md. -- During certain mornings in her 28 years in the Army, Julia Kelly would take her troops outdoors, where she could feel the cool air coursing through her lungs and the warmth of the sunshine upon her cheeks.

The now-retired command sergeant major would ask her Soldiers to take deep breaths and clear their minds from negative thoughts and emotions.

Travelling through the countryside became her welcome retreat growing up in rural southern Montana in one of the largest settlements of the Crow people, a tribe of Native Americans who originally settled in the Great Plains. Also known as the Apsaalooke, or "children of the large-beaked bird" her people share a sacred bond with the land.

She applied Crow principles during her Army career that helped her rise to the service's highest enlisted rank. Since her retirement in 2010, she still contributes to the Army as an ammunition test coordinator at the Redstone Test Center in Huntsville, Alabama. She also volunteers her time speaking to women on overcoming domestic abuse and she helps serve food to homeless veterans.

Her service to other Soldiers spanned her Army career.

DESERT CALM

Before she deployed to Iraq in 2008, Kelly asked her entire battalion to join her outside for a peaceful walk and deep breathing session. She wanted to show her troops that the dangers of a deployment could not rattle them, because nature would grant them an inner peace, even in Iraq's harsh climate.

After her 299th Brigade Support Battalion from Fort Riley, Kansas, arrived in Iraq, she would gather troops together before the brigade combat security team departed for morning runs through the streets of Baghdad.

With sage and cedar mailed to her from relatives, she would bless the vehicles and Soldiers and recite a morning prayer -- a sacred Crow tradition to give thanks. More importantly, she performed a ritual called "smudging," asking for protection from the Creator.

During smudging, she would burn sage with abalone shell and a feather to clear the body and mind of negative energy, and to protect her Soldiers from harm. She would ask her Soldiers to face toward the east into the sun which signals the start of a new day.

Spirituality is believing "in something greater than yourself," she said.

As she would for her own children, she asked for protection before the daily missions into dangerous areas. Soon, crews on other vehicles caught wind of Kelly's blessings and asked the sergeant major to do the same before they left the base.

Kelly said she could not protect herself, though, when she lived in Billings, Montana, 37 years ago as a 21-year-old nursing assistant.

ESCAPING A TROUBLED LIFE

She had left Montana without looking back. She had departed Billings with little but a few suitcases of clothes, her two young children and the bruises on her body.

Powerful fists had beaten her. The father of her eldest children had stalked her.

In May 1981, he waited outside the hospital where she worked in Billings to confront her. Other times, he waited outside the two-bedroom apartment where she raised her young daughters.

At the time, Kelly had been working toward her nurse's assistant certification, while her ex-boyfriend drank and took drugs.

Kelly said she had filed reports with the police, but a restraining order did not stop him.

Billings had been a far cry from reservation life in rural Pryor, Montana. Her aunts and uncles raised cattle and lived in a mostly farming community. During springs and summers, Kelly went from creek to creek, riding horses and occasionally swimming. She shared a close-knit home life with her extended family. Throughout the year, Crow people held ceremonies and traditional social gatherings where they took part in native dances, music and dressed in native attire.

The incidents in Billings shook her to her core. She turned to her extended family for help, but few could do anything.

So, Kelly wanted to leave Montana and the life she knew to become free of the abuse that haunted her. She did not want sympathy or pity.

"I wasn't going to live like that," Kelly said. "I was just determined."

She wanted to find a better place to raise her two young daughters away from the abuse and the constant fear.

On that particular day, her ex-boyfriend's rage had left her black and blue from her neck to her chest. She had two black eyes.

Even before the incident, she called her brother, Bill, for advice.

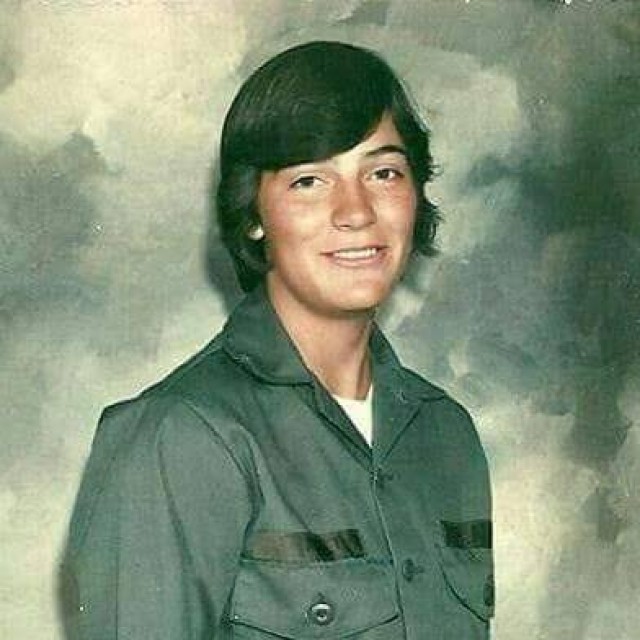

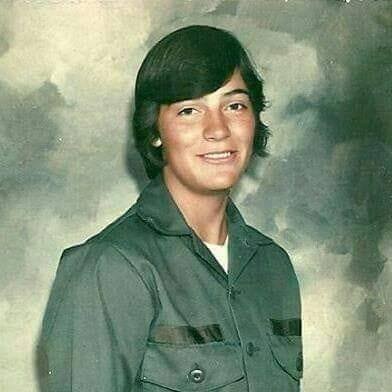

Her brother, who also joined the Army at about the same time, encouraged her to join. She completed initial entry training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and returned to Billings to serve in the Army Reserve.

After the incident at the hospital, though, she asked her recruiter to process her for active duty.

"If I don't get out of here," Kelly told her recruiter. "I'm going to be dead by the time I do anything with my life."

Shortly after, Kelly received orders to Fort Hood, to work as an ammunition specialist.

TOUGH TRANSITION

She entered the Army as a quiet and quick-tempered young woman, but the military would change Kelly in ways she had never imagined.

"I was angry," she said. "Angry about the whole situation of having to leave home. But at the same time I wanted to be safe."

She did not make friends easily as a young Soldier. During her first few years in service, she didn't say many words. Once, when another young Soldier taunted her, she responded by knocking him out cold.

But she learned her job quickly. And diligent preparation became her mantra. Instinctively, Kelly learned from the leaders who surrounded her and she always kept the philosophy of her people, to look after others.

She studied others meticulously from a distance. She took notes on how to make the next rank. But she said that female Soldiers had to walk a fine line to rise through the Army's ranks. Less than .01 percent of females in the military make the rank of command sergeant major.

"It could be tough," said retired Chief Warrant Officer 3 Jo Ann Babcock, a longtime friend. "You had to be tough ... to not show too much sympathy or be too girly."

Kelly said other military leaders accused her of not being deserving of her place, but she remained unshaken, adamant that she would continue to uphold the standards of her own moral code and taking care of Soldiers regardless of performance or background.

"She was like a bulldog," Babcock said. "Because she was determined and was not going to let anyone tell where what she could not do."

TOUGH LOVE

Now at age 57, Kelly speaks in soft, and at times, inquisitive tones. Though, in an instant, her voice can become harsh and blaring.

While serving, she didn't hesitate to call out troops who failed to meet expectations of being in the military, such as reporting on time for formations or appointments. But she willingly gave her Soldiers a second chance, providing they remained open to taking them.

Kelly recalled how she would have to counsel Soldiers who didn't meet standards or had trouble paying bills. Sometimes she had to step in when non-commissioned officers engaged in inappropriate relationships with subordinates.

During one unit formation at Fort Riley, Kelly's unit attended a sexual harassment briefing prior to a deployment. Soldiers, both male and female, began to joke and laugh as the instructor spoke. Kelly stood up from her seat and asked the instructor to stop the class.

"I've heard enough," Kelly recalled saying. "I don't talk about this, but before we get ready to roll you ought to know something. You think as you're trucking along in the military, you think (sexual harassment is) not going to happen to me. You know what guys, it (can happen to you)."

Kelly talked about a time in her life when she became a victim of sexual assault. The classroom fell silent. It was the first time she addressed sexual assault publicly as a sergeant major.

COPING

The difficulties of her home life and stresses of working in the military admittedly took their toll on Kelly. But she never allowed it to fluster her.

When she had a moment to herself, she would drive for miles to find solace from the world. She hiked trails near Alabama's Sand Mountain, or trekked along the banks of the Tennessee River, or simply removed her shoes to feel the earth beneath her feet.

"It's a healing thing," Kelly said. The Alabama resident explained that Crow believed nutrients enter the body by walking barefoot, and provide protection from various illnesses.

She said she also sought the help of counseling and on occasion she confided in close friends.

As a mother and in her career, Kelly found comfort in bringing comfort to others. She carried those maternal instincts with her onto the battlefield and in dealing with Soldiers' problems on the home front.

She cared for Soldiers, "the same way I cared for my own children," she said.

She continued to care for others even after her retirement from active duty in 2010. She volunteers her time at the Downtown Rescue Mission center in Huntsville. She also serves as treasurer for Redstone's Sergeants Major Association and as secretary for the Huntsville Chapter of Women Veterans Interactive.

She recently attended the 2018 Women Veterans Leadership and Diversity Conference in Washington earlier this month, where she networked with other female leaders.

And while she kept the native philosophies of her people close to her, she did not return to Montana for six years. She finds today she can no longer speak the native Crow language fluently. She also finds it difficult to talk about life on the reservation, as young Crow tribe members succumb to common vices, including alcohol and drug abuse.

When she grew up in Pryor during the 1960s and 1970s, she said the community did not face the same social troubles it faces today. The tribe's elders can no longer pass on the tribe's ancient knowledge and traditions to troubled young Crows.

"You can't be a spiritual (leader) if you're on drugs and alcohol," Kelly said. "You don't have the right."

Former and current Soldiers still keep in touch with her. Some Soldiers from outside her former units still make contact. They send her emails, instant messages and check in with her on social media.

Babcock said Kelly's methods may have seemed unorthodox to other Army leaders, but they had a lasting impact.

"As a young person or a young Soldier and you see that person that's got that 'no matter what' attitude and doesn't give up," Babcock said. "It gives you that renewed sense of worth. It makes you keep on trying."

When Kelly speaks to victims of domestic abuse, or homeless female veterans, she bears a similar message.

And sometimes she takes them outside to look east, toward the sun.

"I let them know that every day is a new day," Kelly said. "And that no matter what is happening today, there is hope. You have to have faith."

Social Sharing