In the decade of the 1950s, while the nation's senior political and military leaders opposed the possible spread of communism in Indochina and Korea, the U.S. Army addressed myriad details of how the service would best make use of its limited post-World War II aviation assets in the rapidly evolving battlefield of the nuclear age.

Of even greater concern was how it could modernize and expand such assets in terms of newly-developed doctrine, organization, equipment and pilot training to transform and revitalize concepts of traditional horse-mounted cavalry by freeing such a force from the limitations of terrain, distance and speed.

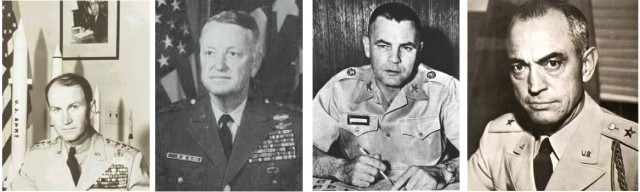

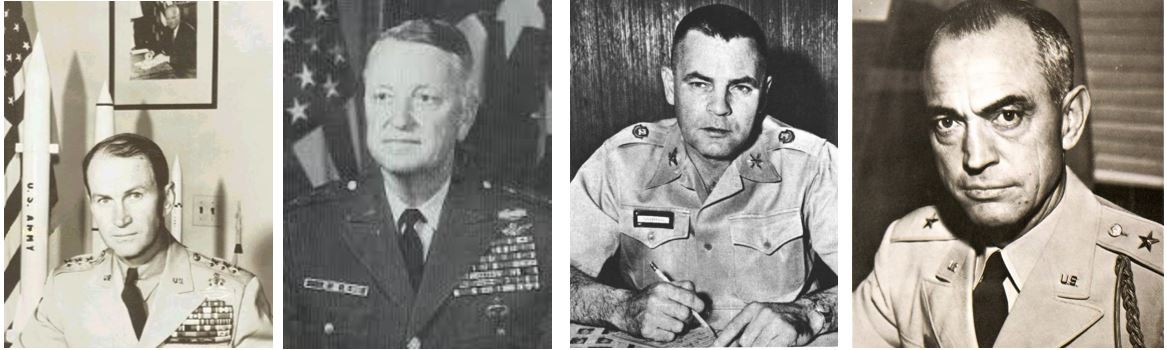

Among the hundreds of Soldiers engaged in helping to remake organic Army Aviation in the wake of the National Security Act of 1947 which created, among other things, a separate Department of the U.S. Air Force (USAF), were Lt. Gen. James M. Gavin, Lt. Gen. John J. Tolson III, Col. Carl Vanderpool and Brig. Gen. Carl I. Hutton.

Concerned with ground commanders' need for greater mobility and sustainability on the nuclear battlefield posited in the opening years of the Cold War, these leaders served as the theorists, investigators, developers and advocates of Army Aviation doctrinal, organizational and materiel innovations not specifically devised for, but which would be proven in combat during, the Vietnam War.

The Emergence of Airmobility and the "Sky Cavalry" Concepts

In his article, "Cavalry, and I Don't Mean Horses," published in the Apr. 1954 edition of "Harper's" magazine, Lt. Gen. "Jumping Jim" Gavin argued for the use of airlifted mechanized troops to serve as a modern form of cavalry. Before winning fame for his combat jumps while commander of the 82d Airborne Division in World War II, Gavin literally "wrote the book" on the Army's effective use of paratroopers and gliders in combat. Coming as it did in the final months of the Korean War, his article helped spur the efforts of pioneers like Hutton and Vanderpool, who also built on their observations of the Army's use of helicopters in Korea to advance the actual implementation of airmobility and the "Sky Cavalry."

Tolson, another contributor to the expanded use of helicopters in combat, defined airmobility in his 1999 monograph entitled, "Airmobility, 1961-1971." He described the term as a "concept that envisages the use of aerial vehicles organic to the Army to assure the balance of mobility, firepower, intelligence, support--and command and control. The story of airmobility in the Army is inextricably interwoven with the story of Army aviation."

As director of the Airborne-Army Aviation Department of the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning in 1955, Tolson and his group brought together "the necessary people and equipment to develop procedures, organizational concepts and materiel requirements for airmobility." One thing that he emphasized in his account was that "the airmobility concept was not a product of Vietnam expediency." Instead, he traced the theory back to its earliest roots in the airborne operations of World War II and the impact of the helicopter's use in Korea. According to Tolson, "Although Vietnam was the first large combat test of airmobility, air assault operations in Southeast Asia would not have been possible without certain key decisions a decade earlier…. The mid-fifties were gestation years for new tactics and technology."

A Separate Aviation Branch

One area of concern in the 1950s the time for which would not come for another 30 years was the push for the creation of a separate aviation branch in the U.S. Army. Staff members within Headquarters, Department of the Army (DA), first raised the issue during a comprehensive review of the service's organizational elements ordered by Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army from Aug. 13, 1953 to Jun. 30, 1955. At a conference held on Dec. 7, 1954, those who either supported or opposed the plan continued the "intense internal controversy" sparked by the initial review.

Individual advocates such as Maj. Gen. Paul Adams argued the new organizational element was a necessity because of the growing size and complexity of Army Aviation. Established groups within the Army as it existed in 1954, however, rejected the idea for a variety of reasons. For example, Field Artillery did not want to see a repeat of the separation that resulted in the loss of much of its control over artillery observation aircraft in World War II, while the Transportation Corps "proposed putting all aviation under its jurisdiction."

Representatives of the newly established Army Aviation School resisted both separation and consolidation, calling instead for the "dual proficiency" of trained pilots who remained aware of and concerned about ground combat issues and needs. Still others urged caution out of concern about opposition from the U.S. Air Force.

Almost 20 years later, in his article, "The Soldier-Aviator," published in Apr. 1970 in the "U.S. Army Aviation Digest," Brig. Gen. Sidney B. Berry, then assistant commandant for the U.S. Army Infantry School, reiterated the earlier argument for "dual proficiency." In light of combat experiences in Vietnam Berry maintained, "Aviation and ground battles in today's Army are not separate functions but a combination which form an unbeatable team…. The aviator is a flying soldier who is always a soldier first and an aviator second…. But Army aviators are more than just plain soldiers. They are soldiers with special aviation skills and capabilities which they put at the service of all other soldiers in our Army…. Army aviation is an integral, organic part of ground operations."

Creating the Army's Rotary Wing Gunships

An armed helicopter is defined commonly as a "military rotary-wing aircraft equipped with ordnance … designed specifically for a ground attack mission, or … (possibly) a modified version of aircraft designed for other use in which weapons are added later rather than being part of the original design."

According to a Jul. 1971 article written by Lt. Col. Charles R. Griminger, "Interest in arming helicopters began as early as 1940 with Sikorsky's development of the R-5 helicopter." But Army interest in designing a mount for a 20-millimeter (mm) cannon to be installed in the nose of the aircraft, which began in 1942, ceased five years later once the former U.S. Army Air Corps became the independent USAF. Subsequent experiments to weaponize helicopters continued in 1950 when the Army and the Bell Helicopter Company collaborated on mounting a bazooka on the OH-13 Sioux aircraft. In the first part of his article, "The Armed Helicopter Story," Griminger also noted, "The first armed helicopter in combat was probably devised during the Korean War, when the helicopter received its baptism of fire in the early 1950s. Aviators are known to have fired their weapons from the open doors of helicopters."

Other branches of the U.S. armed forces also pursued the same goal, but for a variety of uses often unique to their own service. For example, the U.S. Navy saw rotary wing aircraft as useful platforms for anti-submarine weapons as well as for search and rescue operations. The Air Force relegated such aircraft to personnel transport under certain conditions, while the Army and U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) relied more heavily on helicopters to move supplies and ammunition.

In addition, "with the increasing use of the helicopter for infantry transport, the U.S. Army saw a need for specialized helicopters to be used as aerial artillery to provide fire suppression and ground support close to the battle." Allied nations such as the United Kingdom and France deployed the increasingly ubiquitous helicopter to the battlefield in similar fashion during the 1950s.

The Army's real need for such airborne firepower first surfaced in Korea in 1952 with the deployment of the UH-19 Chickasaw helicopters. One Army officer whose interest in the combat potential of rotary wing aircraft was Col. Jay D. Vanderpool, a non-aviator who closely observed helicopters in action during both World War II and the Korean War. In the latter conflict especially, Vanderpool's first-hand experience with the helicopter came while he was assigned to a combined joint "cloak and dagger outfit" that made use of Air Force UH-19s when "engaged in military operations behind enemy lines." One thing that disturbed both the pilots and the crew was the fact that the aircraft was not armed.

Although the urgency for weaponizing the helicopter diminished with the Korean War cease fire, advocates of such a system remained committed to a future Army strengthened by the addition of this kind of aviation asset. Starting in 1953, the next two years saw several independent efforts to arm military helicopters, such as that undertaken by the 24th Infantry Division in Japan, unit members of which mounted a makeshift grenade launcher on an OH-13. Moreover the French army in Algeria installed machine guns in the doors of helicopters being used to put down armed rebellion.

One of the most ambitious experiments in this period was that dubbed Project Sally Rand. Teaming with the manufacturer, the Ballistics Research Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md., equipped a Hiller YH-32A "Hornet" with launcher tubes for two-inch rockets to evaluate the possibility of the stripped-down helicopter in an armed role. Although this aircraft never became part of the Army inventory, Hiller considered its ultralight, ramjet-powered aircraft to be the "first helicopter gunship."

However, at the heart of the Army's growing efforts to equip helicopters with guns and rockets in the 1950s was the Army Aviation School, originally established at Fort Sill, Okla., then moved to Fort Rucker, Ala., in 1954. Leading this move was Brig. Gen. Carl I. Hutton, whose actions in support of arming the helicopter and devising workable "Sky Cavalry" equipment, doctrine and organization modifications earned him the honorific "Father of Attack Helicopters."

A West Point graduate who first served in the Field Artillery, Hutton learned to fly at Fort Sill shortly after World War II. He subsequently became commandant of the Army Aviation School while it was still located in Oklahoma. After overseeing the school's move to Alabama, Hutton continued to guide the Army's aviation training program from Jun 1954 to Jun 1957.

As commandant, Hutton used the resources within his jurisdiction to cultivate a climate of creative weapon system experimentation as well as doctrinal study and design of armed airmobile tactical organizations. "An aviator of exceptional ability," Hutton's frustration with the unfavorable evaluation by non-aviators of the "Sky Cavalry" segment of Exercise Sagebrush in 1955 pushed the former field artillery commander to pursue his vision of what he termed "an air fighting army." In Jun. 1956, Hutton asked Col. Jay Vanderpool to oversee an as-yet unsanctioned and unfunded research and development program "to prove the feasibility of arming helicopters and developing a 100 percent armed airmobile force."

By the time Vanderpool was named director of the Aviation School's newly established Combat Developments Office in 1958, preliminary efforts at Fort Rucker had expanded from a small group of dedicated aviators and enlisted men who "worked on experimental weapons systems during weekdays and experimented with tactics and techniques on weekends when the school was closed" to the standup in Mar. 1957 of a functioning provisional "'Sky Cav' platoon notorious for its hair-raising demonstrations of aerial reconnaissance." As Vanderpool recalled in his article "We Armed the Helicopter" published in the "U.S. Army Aviation Digest" in Jun. 1971, "The helicopter was the 'ugly duckling' of aviation in the mid-1950s. But there were a few who dared to think of it as a weapons system and the key to successful airmobile operations. Today there are few who would think of going into combat without the helicopter."

Throughout the 1956-57 period, "Vanderpool's Fools" scavenged needed equipment and material. Their perseverance and hard work paid off by mid-1957 when the group had expanded their fleet from one OH-13 Sioux helicopter to six OH-13s, two OH-21 Shawnees, one H-25 Army Mule and one UH-19 Chickasaw rotary wing aircraft. In addition, the intrepid band of experimenters "scoured the country looking for weapons to test on helicopters. Any idea that looked reasonably feasible was tried. We mounted weapons on every type of helicopter available to the school. We employed obsolescent, standard and prototype weapons."

They asked for and received assistance from the Navy and Air Force; industry representatives such as Bell Helicopter, General Electric and the Rocketydyne Division of North American; other commands within the Army, such as the Ordnance Department, the chief of which in Mar. 1957 was ordered to develop machine gun installation kits for OH-13, OH-21 & OH-34 helicopters as a result of Vanderpool's work; as well as other Army arsenals and depots engaged in weapon systems research. One such installation was Redstone Arsenal, where the Army's rocketry and missilery programs had been consolidated starting in 1948. Fifty years before the establishment of the U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command (AMCOM) in 1997--which still supports aviator training at Fort Rucker through the Aviation Center Logistics Command (ACLC)--elements of AMCOM's predecessor commands at Redstone helped support Fort Rucker's early efforts to arm the helicopter.

Recollected Vanderpool, "The rocket people at Redstone Arsenal had a prototype 2-inch folding fin aerial rocket (i.e., the T-290). We tested it with both 6-foot and 10-foot launching tubes, but the warhead was too small for antitank (while) the weight and bulk penalties were considered excessive for antipersonnel. We soon expended the limited stock of (T-290) rockets at Redstone." Moreover, on Jun. 10, 1957, the recently established "Sky Cav" platoon demonstrated the fruits of its labor at a conference of the American Ordnance Association held at the arsenal. Using the aforementioned fleet of helicopters, the team demonstrated both its weapon systems prototypes and its evolving armed airmobile doctrine, organization and tactics. A notable change to the unit's usual array of weaponized helicopters was the addition to the platoon's OH-13s of .30 caliber machine guns and Oerlikon rockets, the latter a Swiss Army unguided antitank armament evaluated by the USAF.

In addition to the hardware modifications undertaken by Vanderpool and his group, they also made use of doctrinal, organizational and tactical views originally designed for the combat use of traditional horse cavalry. Incorporating many of the "Duke of Wellington's concepts of cavalry, dragoons and artillery employment," along with U.S. Navy tactics which allowed its surface vessels "to maneuver in any direction on a horizontal plane," Vanderpool also admitted to plagiarizing "the last field manual written for horse cavalrymen in 1936…. Chapter by chapter, we rewrote horse cavalry tactical doctrine into air cavalry incorporating our lessons learned."

In Nov. 1957, the original "Sky Cav" platoon became the Aerial Combat Reconnaissance (ACR) Platoon, Provisional (Experimental). General Order 68, dated Mar. 24, 1958, reorganized the unit as the 7292d ACR Company (Experimental) under command of Third Army. The company's assigned mission was "To support the Army Aviation School with 100 percent of its personnel and equipment in the conduct of approved training programs and in the development of tactical doctrine, organizational data, operational concepts, material requirements, tactics, techniques and procedures for employment of a completely airmobile combat force."

Fort Rucker personnel later briefed then Maj. Gen. Hamilton H. Howze, the first Director of Army Aviation and long-time airmobility advocate, on the organization of an "Armair" Division. In Mar. 1959, the 7292d began a series of reorganizations and renaming that resulted in the standup in 1965 of the 1/9th Cavalry, which was sent to Vietnam as part of the Army's initial airmobile unit, the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). In his 1971 article, Vanderpool noted, "The airmobile division proved to be an undisputed success and justified the faith that the late Gen. Hutton had placed in armed helicopters and airmobility just ten years earlier."

Prior to this validation, however, the Army would convene two review boards in the 1960s to study requirements and make recommendations for the implementation of "an air fighting army." And, more importantly, the first Army unarmed aviation units--fixed-wing and helicopter--arrived in Vietnam in Dec. 1961.

Social Sharing