FORT MONMOUTH, N.J. (Army News Service, July 22, 2008) - Sixty years ago, the United States had two armies - a white Army and a black one - said a World War II veteran of an all-black infantry unit.

Retired Master Sgt. Alden Small, a 22-year Army veteran and 42-year civil servant, was drafted into the segregated Army in 1942, and later helped educate other African-American Soldiers, enabling them to remain in the Army after the war and join integrated units in the 1950s.

<b>Truman's order</b>

Integration was possible because of Executive Order 9981, signed by President Harry Truman on July 26, 1948. It called for equal treatment and opportunity for black servicemen.

"I would say that the Soldiers, especially Soldiers of color, don't realize what we've gone through, the Soldiers prior to them," Small said. "And I'm happy to see that they're benefiting now from the things that we've done in the past."

With some notable exceptions, African-American Soldiers had previously been relegated to mostly service jobs, such as digging ditches, while their white counterparts were eligible for elite combat units, according to Robert Hodges Jr., in an article in "World War II" magazine.

<b>"Buffalo Division"</b>

Small was one of those exceptions. He served in the 92nd Infantry Division, which he called the "92nd Buffalo Division."

"We were the only black division, full-line division, to fight as a division in World War II. All the other so-called Negro organizations were splintered organizations, such as a regiment here, a battalion there and so forth. But we fought as a division," said Small.

According to the 92nd Infantry Division Association, most of the Soldiers were from the rural, segregated South with little or no education. Many could not read.

With a year of college, Small became the medical supply sergeant for the entire division.

<b>Italian Campaign</b>

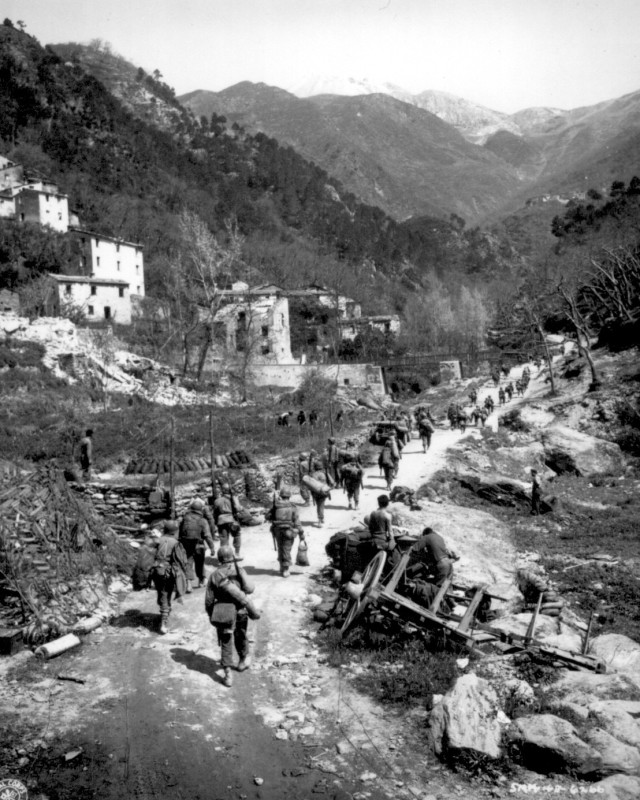

The 92nd deployed to Italy in the summer of 1944 as part of the Fifth Army. According to Small, they took part in the Rome-Arnold campaign, captured Genoa and fought along the Ligurian Sea and across northern Italy.

According to the Center for Military History, the 92nd faced large amounts of artillery and machine gun fire from surrounding mountains and fortified Italian castles as they pushed through the German, or "Gothic," line.

When hostilities in Italy ended on May 2, 1945, almost 3,000 men out of 12,846 had been killed, captured or wounded. The division had captured nearly 24,000 prisoners and earned more than 12,000 decorations and citations, including two Medals of Honor, although these were not awarded until 1997. Small received the Bronze Star.

<b>Gillem Board</b>

After the war ended, there were demands for the desegregation of the armed forces and within months, the Army established a board headed by Lt. Gen. Alvan C. Gillem Jr. to study its racial policies.

Its report stopped short of calling for integration, but according to the Center for Military History, was significant in that it called for fair treatment of African-American Soldiers and made integration the ultimate goal.

But at the same time, in 1946, the secretary of war temporarily suspended black enlistments in the Army and in October of that year, the Army established a score of 100 on the Army General Classification test for blacks, while whites only needed 70 to pass.

<b>Educating Soldiers</b>

Some units moved forward on their own. The Army in Europe, under Lt. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner, began educating African-American Soldiers to help them pass the test in 1947.

"There's an old saying that after they've seen Paris, they don't want to go back to the farm. Well, a lot of the fellows remained in the service. In order to integrate the Army, many things had to be done, and one of the things they decided to do was to bring the Soldiers up to at least an eighth-grade education," said Small, who had remained in the Army and was posted in Germany.

Describing the program, called On-Duty Education, he said teachers came from the States to teach educated Soldiers and non-commissioned officers how to teach the Soldiers.

"We would teach them the basics, from first grade, in many cases, to eighth grade. And at the end, they would take a test and if they passed, they were allowed to remain in the Army," said Small, who taught black Soldiers half of every day in Kitzingen.

"There was hostility," he continued. "White Soldiers felt that the Negro Soldiers were at an advantage being able to go to school. Because, of course, a lot of the white Soldiers came from the farm also, and they needed an education too."

The newly-trained Soldiers, according to the Center for Military History, showed an improvement in morale, a dramatic drop in numbers of court martials and a more intelligent approach to social diseases.

<b>Integration</b>

Following Truman's 1948 order, integration of the armed forces unfolded throughout the early 1950s - more than a decade before similar programs in the segregated South.

"As I visualize it, you'd see a truck of all-black Soldiers headed for a white unit and a truck of white Soldiers headed for a black unit. And it took about a month to actually integrate the Army overseas," said Small, referring to the integration of the Army in Europe in 1952.

"I think I helped the country because we were in a difficult time right after World War II," he said. "Soldiers were fighting and dying overseas and coming back and being lynched and so forth. There were some terrible times. And I think the Army was a big factor in total integration.

"I was given the opportunity early on to go to Officer Candidate School, but I saw the opportunity to help out, to integrate the Army, and I had a good feeling about it. This is something I'll never forget. I enjoyed doing it. I enjoyed seeing the Soldiers feeling that they had obtained something," Small, who retired from active duty in 1965, explained. He plans to retire from civil service and write a book on his experiences --someday.

(Editor's note: The original version of this article appeared in the "Monmouth Message" in September 2006. Articles by Ulysses Lee and Morris J. MacGregor Jr., both of the Center for Military History, contributed to this report.)

Social Sharing