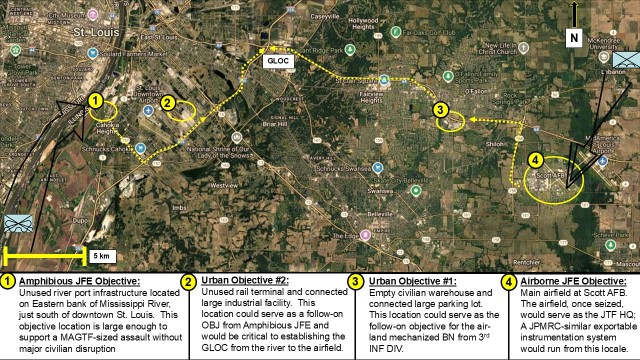

The time is 0200. Over the next 18 hours, a joint task force (JTF) led by the 82nd Airborne Division will open a convergence window for a joint forcible entry (JFE). A Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) will conduct an amphibious assault to establish a beachhead. Inland, an airborne infantry battalion and a Ranger battalion will seize an airfield. After establishing both lodgments, the JTF must establish a ground line of communication (GLOC) between the beach and the airfield by fighting its way through dense urban terrain (DUT).

This, however, is not a real-world mission but a hypothetical training exercise held near St. Louis, MO. The exercise builds U.S. Army and joint interoperability by expanding upon the Army’s “Divisions in the Dirt” (division integrated) concept. As the military shifts its focus toward large-scale combat operations (LSCO), division and corps headquarters must become experts in battlefield orchestration — shaping the deep with long-range fires, attack aircraft, and integrated capabilities from the joint force, and sustaining the close to ensure subordinate units can dominate their assigned areas.(1) To win the next fight, divisions and corps must incorporate multidomain capabilities into tactical maneuver in all types of terrain.

The time is right to scale up collective training for the multidomain operations (MDO) era. As a potential solution, the Army should create a Joint Exportable Training Package for Existing Urban Terrain (JET-PEUT) much like the Joint Pacific Multinational Readiness Center’s (JPMRC’s) operating concept. Using the experience of the JPMRC as a model, the Army should create an exportable training capability that replicates a combat training center (CTC) environment in urban terrain in the continental U.S. (CONUS) and elsewhere. The JET-PEUT would provide a way for divisions and corps to train on realistic urban terrain in a live, virtual, constructive (LVC) training environment.

The JET-PEUT’s primary advantage is that it can be extremely scalable, tailorable, and exportable, enabling commanders to conduct each JET-PEUT exercise in specific areas that more realistically portray the reality of today’s battlefield. With the addition of JPMRC, the Army now can train large formations in nearly every operating environment (OE) possible: jungle, archipelagic, Arctic, mountainous, desert, wetlands, forest, riverine, and plains. There is one glaring omission: the modern urban OE. The JET-PEUT aims to address this gap.

Looking Back to Look Ahead

This isn’t the first time the United States has wrestled with the problem of training large formations. In the fall of 1941, as the Germans dominated Europe and the Japanese raced across China, the U.S. Army was struggling to mobilize and train its forces. In response, Army Chief of Staff GEN George C. Marshall devised the Louisiana Maneuvers, a series of large-scale (approximately 400,000 Soldiers) force-on-force exercises in which two armies fought across large swaths of Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Carolinas.(2) These exercises provided field maneuver experience to a green officer and Soldier corps and allowed the Army to test and train on emerging concepts. The Army learned several critical lessons, including the need to integrate infantry and armor formations, the effectiveness of antitank weapons against armored formations, and the potential of tactical close air support.(3)

Similarly, the Army of the 1980s understood more realistic training would be required to defeat a numerically superior Warsaw Pact military in combat. For example, the 1982 iteration of Field Manual (FM) 100-5, Operations, which introduced AirLand Battle doctrine, reinforced the severity of the threat environment: “The conditions of combat on the next battlefield will be less forgiving of mistakes and more demanding of leader skill, imagination, and flexibility than any in history.”(4) This period’s sense of urgency led to the creation of the National Training Center (NTC).(5) Further, the massive success of the LSCO invasion force during Operation Desert Storm is often attributed to the decade of experimentation, learning, training, and field experience reaped from NTC.(6)

The Army is at another training inflection point. Like the two periods listed above, today, the Army and the joint force must construct ways to train divisions, corps, and joint force headquarters in the most realistic settings. Additionally, with modernization progressing across the Department of War (DoW), we must understand what concepts and equipment will work and how as well as what integrated formations and tactics are required for the modern fight. The JET-PEUT can help accomplish these goals.

The rest of this article is divided into two main sections. Section I, “Why Is JET-PEUT Needed?” argues that the time is right to fix the collective training gap in urban combat readiness across the joint force. The JET-PEUT would offer CONUS-based formations an additional option to achieve multidomain warfighting experience at a reasonable cost. Furthermore, the current doctrine and OE demonstrate the need for increased training capability at scale that the JET-PEUT could fulfill. Lastly, the JET-PEUT would offer opportunities to test modernization concepts across the DoW.

Section II, “What Would It Look Like?” uses the JPMRC as a model for the JET-PEUT. It discusses the main challenges in making the JET-PEUT a reality, including exporting an instrumentation system into a civilian environment and scaling up existing DUT training permissions to incorporate brigade-sized or larger formations. Finally, the article returns to the hypothetical exercise introduced at the beginning to discuss how it could be implemented in real life.

Section I: Why Is JET-PEUT Needed?

Maintaining a comparative advantage over our principal adversaries is essential to national security. Army and DoW leadership are laser-focused on this prospect — eliminating waste and obsolete programs to concentrate solely on training and modernizing for the next fight.(7) Army Chief of Staff GEN Randy George has emphasized that the Army must be ready for any fight, anywhere, and to cut any requirement that doesn’t improve warfighting readiness.(8) This is precisely what the JET-PEUT concept is designed to do; it takes these sentiments and presents them in training form. As the Army progresses to Transformation in Contact (TiC) 2.0, it will need additional training options to test new concepts at the scale at which they are designed to function.(9) The current CTC infrastructure could be further optimized to train the division as the unit of action through forward-thinking concepts like the JET-PEUT. The JET-PEUT could improve warfighting readiness by meeting doctrine’s requirements for LSCO in DUT and providing a needed venue for experimentation, innovation, and training.

First, the JET-PEUT would help meet current U.S. Army doctrine requirements for large-scale conventional ground forces to conduct MDO in DUT. FM 3-0, Operations, states conducting combined arms operations in DUT that integrate joint capabilities, allies and partners, and conventional and irregular forces will be essential to future success.(10) Army Training Publication (ATP) 3-06/Marine Corps Tactical Publication 12-10B, Urban Operations (UO), further stresses the importance of UO proficiency in future conflict — though it does note the difficulty in replicating the complexity of urban terrain in a training environment — such as working infrastructure, high numbers of noncombatants, and the underground, surface and super-surface spaces that impede maneuver.(11)

No doctrine, however, suggests a method to train large formations for urban combat beyond stating that it will be necessary and begins with small unit mastery. Additionally, most urban training facilities at home stations are platoon-level military operations on urban terrain (MOUT) facilities constructed of container express (CONEX) boxes and lacking infrastructure. CTC facilities are more realistic: The Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) includes 18 villages (the largest containing 51 buildings), while the Indiana National Guard’s Muscatatuck Urban Training Center (MUTC) includes 120 buildings.(12) However, the current limitations in size, density, and vertical features — coupled with insufficient noncombatant players — result in a lack of realism.(13) As a result, units cannot train on critical tasks ranging from urban navigation to air-ground coordination in an urban OE. The JET-PEUT could close this gap.

(Photo courtesy of Indiana National Guard) VIEW ORIGINAL

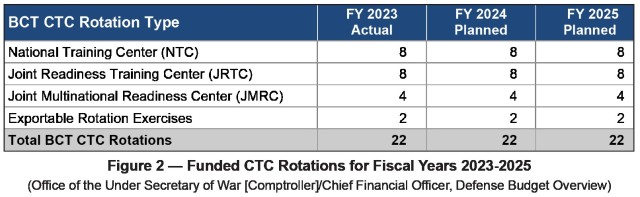

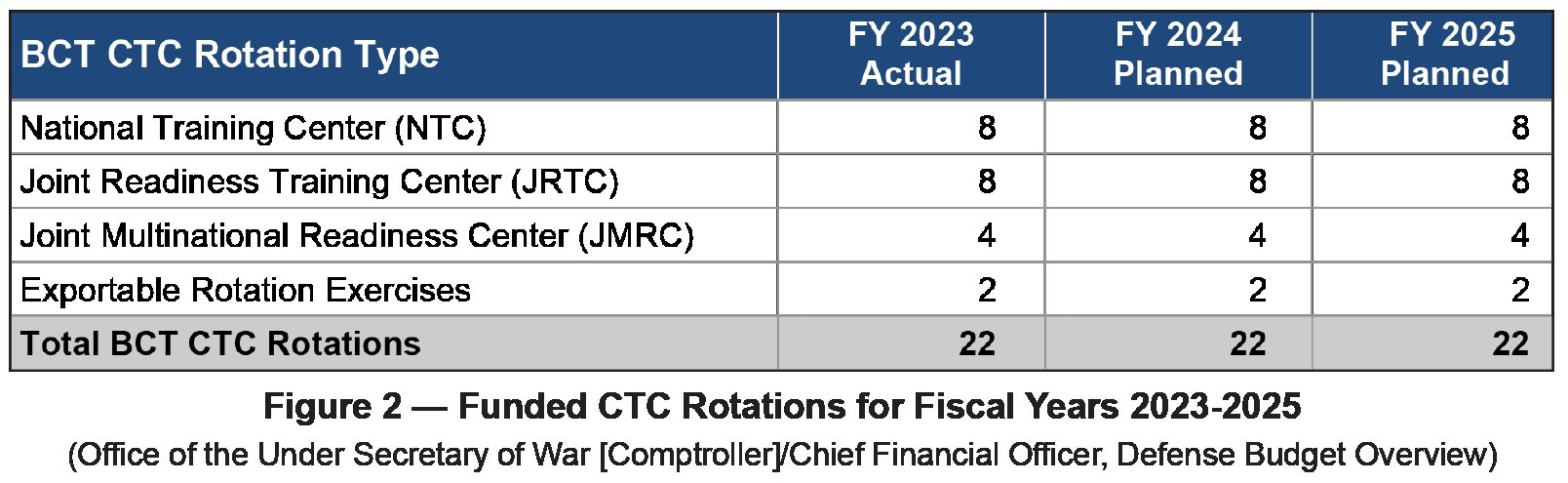

Next, the JET-PEUT could provide a way for the Army to identify the optimal task organization to meet the challenge of LSCO in DUT at a reasonable cost. This is a problem set that TiC 2.0 is designed to help solve. Yet, current CTC rotations are still designed around a single brigade combat team (BCT), costing tens of millions for each rotation. Consider the Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 DoW budget allocation of 22 fully funded CTC rotations.(14) For FY25, only two full-scale Division in the Dirt rotations were scheduled, with four additional rotations supported by division tactical headquarters (DTAC).(15) This is terrific output, and these rotations’ consistently high level of warfighting readiness is essential. However, a significant portion of the current funding stream is still being devoted to training individual BCTs with minimal focus on joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational (JIIM) and multi-component interoperability. If something like the JET-PEUT could be allocated to four or five rotations annually, the number of headquarters trained by division-integrated rotations could increase by 50 percent. A more creative use of the current funding stream could result in an increased overall readiness assessment (RA) rating across the Army regarding capacity and capability measurements for combat.(16) Thus, a larger number of formations and headquarters certified for combat could be achievable in the near term.

Third, the current OE demonstrates the need for a capability like the JET-PEUT that will drive the rapid innovation required for successful MDO in DUT. The 2022 Battle of Kyiv between the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) and the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (AFRF) provides an excellent example. This battle involved sophisticated MDO in an incredibly complex OE: a densely populated, modern European city with advanced infrastructure, extensive underground spaces, highways, waterways, canals, bridges, DUT, and peri-urban sprawl interspersed with forests and significant elevation change. As the battle played out, jamming and counter-jamming operations co-occurred over civilian electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) traffic, all severely degrading communications and equipment performance on both sides.(17)

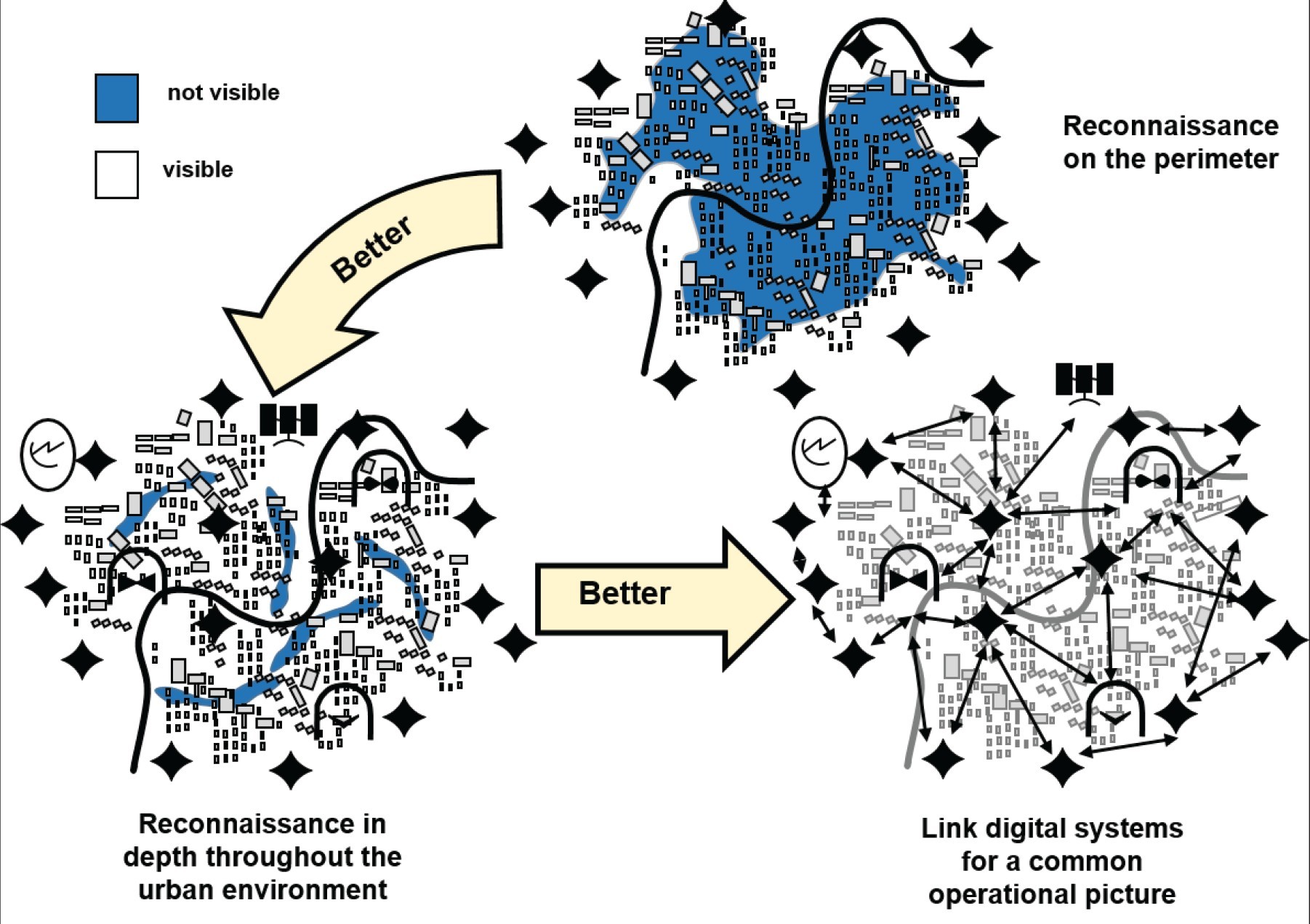

The AFU was the first to realize the importance of maintaining situational awareness by any means possible. The Ukrainians fused critical information flows into an advanced battle network and overlayed it on top of an effective natural and man-made obstacle network, making Kyiv an MDO nightmare for the attacking forces.(18) This intelligence fusion system, called Delta, collected and processed a wide range of information from closed-circuit cameras, traffic cameras, drones, satellites, human intelligence, foreign partners, and other sources into a common operating picture (COP) — tracking the Russian invasion force in real time.(19) Although Delta and other key innovations had been developed and improved since Russia’s initial incursion into Crimea in 2014, their rapid employment and ease of use was a combat multiplier for the Ukrainians.(20) Delta considerably improved the Ukrainians’ targeting ability, shortening the sensor-to-shooter cycle and enabling Ukrainian artillery, drone teams, and ambush units to engage more targets faster and allocate limited resources effectively.

However, not all innovations or MDO tactics favored the Ukrainians. The Russians began their invasion with a massive multidomain onslaught designed to overwhelm Ukrainian defenses. It consisted of an initial electronic warfare attack to degrade Ukrainian air defense systems, coordinated airstrikes against a broad range of tactical targets, and cyberattacks against Ukrainian governmental infrastructure — all designed to support a swift coup de main of the Ukrainian capital via an air assault and several armored columns.(21) Most of these operations succeeded. Russian deception efforts, designed to fix AFU combat power in the Donbas, were also mostly successful.(22)

Ultimately, however, the Russians failed to seize the capital as they struggled to synchronize and sustain their various lines of operations. The disparity in situational awareness repeatedly favored the AFU, and they capitalized. This battle provides a clear example for why something like the JET-PEUT is needed. As the Army and joint force expand use of the Maven Smart System and other Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) concepts, it will need an arena to test their capabilities and limitations at the scale and conditions necessary for success on tomorrow’s battlefield.(23) Wishful thinking that current battlefield digitization platforms will work as designed when the OE devolves into a situation of maximum complexity is no longer sufficient.

Lastly, in an era where unmanned aerial systems (UAS) fill the skies, it’s increasingly difficult to keep command posts (CPs) undetected and protected from enemy indirect fire (IDF). Using existing hardstands, basements, and underground facilities for CPs is emerging as a best practice, especially in Ukraine.(24) These locations protect CPs from detection and IDF, mask electromagnetic emissions, and can be made to look inconspicuous.(25) However, current division and brigade CPs may not operate this way nor train their Soldiers to establish this type of CP configuration. Several TiC programs and Command and Control (C2) Fix initiatives are designed to enable smaller, more survivable command posts.(26) Still, these efforts will require consistent and realistic training to ensure their functionality. The JET-PEUT could offer an avenue to develop urban-specific tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) before the outbreak of conflict and before American lives are put at risk. Think “Divisions in Concrete” to accompany the Divisions in the Dirt concept.

This figure from ATP 3-06 demonstrates the disparity in situational awareness resulting from effective or ineffective reconnaissance and battle network construction before and during urban combat. The top figure, where very little is understood in real time, could be attributed to the AFRF’s experience in attacking Kyiv in the first six weeks of the war. This can be contrasted with the bottom right picture, which demonstrates the AFU’s effective real-time digital situational awareness created by the Delta system and other innovations on the fly, overlayed with the AFU’s internal lines and layered defense in depth. VIEW ORIGINAL

Section II: What Would It Look Like?

Saying that we need to train large formations for LSCO on realistic terrain is one thing, but making it happen is quite another. Implementing the JET-PEUT would be challenging. While not discounting this difficulty, this section uses the JPMRC as a model to demonstrate that the JET-PEUT is possible. It would not be another CTC, but a vehicle to enhance current CTC rotations. It would enable division and corps headquarters to direct realistic tactical operations in the field while stressing joint and interagency interoperability.

First, the JPMRC shows how creating a specific capability can produce intended results quickly. In just over three years, the JPMRC implemented an Army executive order by transforming into a fully instrumented CTC that conducts rotations in Alaska and Hawaii, as well as partnered rotations west of the International Date Line (IDL) through Operation Pathways.(27) JPMRC “builds BCT readiness and partner capacity, assures our allies and partners of our willingness to train where we will fight, and integrates Joint, Multi-Domain, and Multinational Forces” to build relationships and enhance interoperability.(28) Each rotation is division enabled with either the 25th Infantry Division or the 11th Airborne Division serving as both the higher command (HICOM) and exercise support group for each exercise. The significant role played by the division headquarters stresses and stretches division-level systems and provides combat-credible readiness in theater on the region’s terrain.(29) Further, each rotation is unique and constantly evolving, which makes the JPMRC an attractive option for joint service component, special operations forces, and multinational participation. The JET-PEUT could function similarly, offering scalable, exportable JIIM and MDO training under the most realistic conditions and terrain short of combat.

However, we must solve two main problems before making the JET-PEUT a reality. The first is developing an exportable instrumentation system that can be used in existing urban terrain without disrupting the local population. Existing systems — those used at CTCs such as the Home Station Instrumentation Training System (HITS) and the Instrumented Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System (I-MILES) — are large emitters and not designed for use off military installations.(30) Furthermore, large-emitting legacy systems do not replicate the subtle EMS signature of our current adversaries.(31) This complicates training and goes against the forward-thinking approach of the JET-PEUT and similar concepts designed to train the dual objectives of EMS detection and signature masking among ground force elements.

The JPMRC is trying to solve this problem. One success is increasing the use of player unit radios and implementing small private networks with integrated Mobile Ad Hoc Network capabilities.(32) These efforts reduce the exercise’s overall EMS and connectivity requirements and lessen the individual Soldier’s size, weight, and power burden. They also more realistically portray the EMS signature of participating elements. While not a perfect solution that imitates battlefield effects and provides exercise control (EXCON) data, these steps are necessary as the JPMRC looks to increasingly integrate with international partners. Similar concepts could be introduced stateside in the search to safely scale up collective training for LSCO in an urban environment.

The second problem to solve is streamlining the complex coordination required for training off installation. Currently, realistic military training (RMT) off federal real property is regulated by Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 1322.28.(33) This document establishes uniform planning guidance, risk assessment authorities, approval levels, legal and public affairs duties, and the guidelines for coordinating with civil authorities. DoDI 1322.28 understands the limitations of installation-only training, stating: “RMT is critical to force readiness; however, environments replicating those encountered in actual operations may not be available in the size or desired level of realism on federal property. Urban environments are the most complex and difficult to emulate on federal property and are the desired environment for most RMT.”(34)

However, the current approval chain is long, extending from local city councils to county emergency response services and sometimes even to the state level.(35) Establishing a precedent for streamlined exercise approval and civil-military coordination is a crucial first step. As an added benefit, the staff work required to create RMT perimeters outside federal real property will also inherently stress JIIM interoperability. The difficulty involved in greenlighting the exercise is part of the training value.

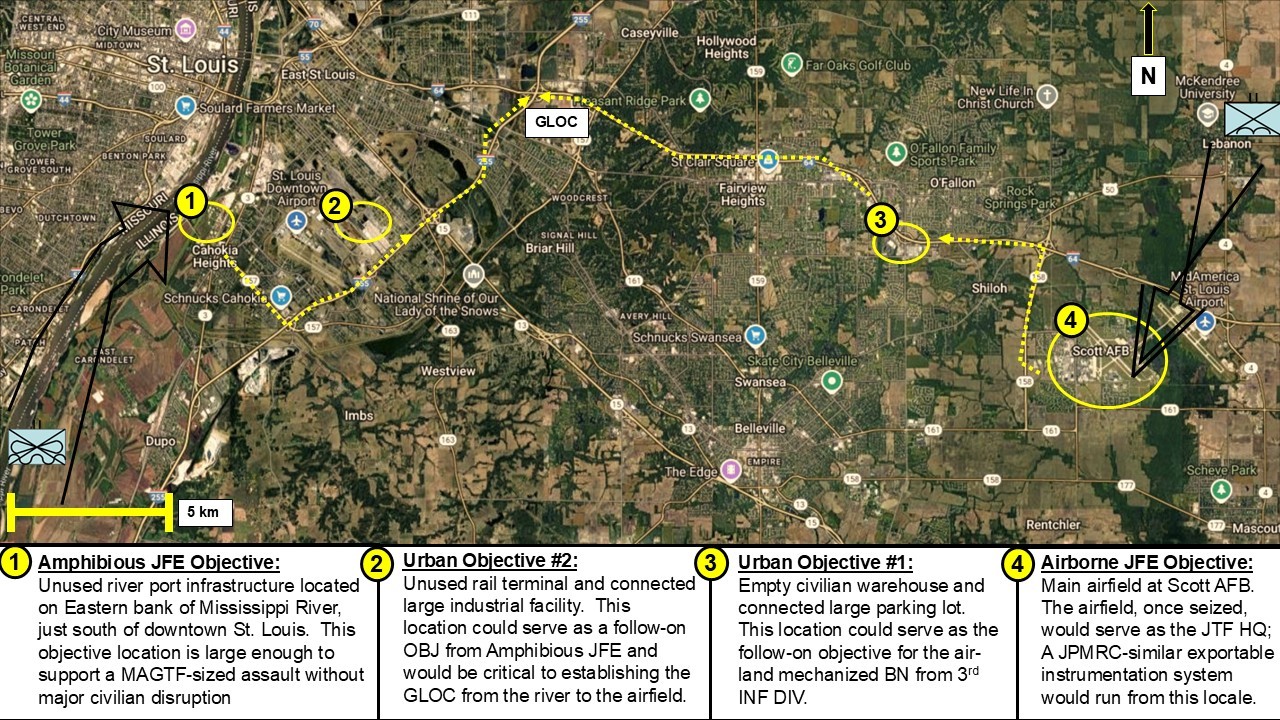

Returning to the example exercise proposed at the beginning of the article, the following description explains what it could look like. Interviews with the JPMRC, the Combat Training Center Directorate (CTCD), and local officials from O’Fallon, IL, helped inform the concept.(36) The hypothetical training area would extend from Scott Air Force Base (SAFB) in O’Fallon to the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, utilizing vacant office buildings, warehouses, and shipping infrastructure in East St. Louis and along the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. The beachhead objective and the pockets of urban terrain would be established under military operations areas to manage military airspace, and DoDI 1322.28 regulations cover the ground maneuver perimeters.(37) The areas would also include spectrum management permissions based on coordination with local and state government officials. These stipulations enhance safety and deconflict with emergency response elements and other civilian agencies.

EXCON could run from SAFB, located about 25 kilometers east of the beachhead objective site on the Mississippi River. SAFB could also house the airfield objective, while the XVIII Airborne Corps, serving as the senior Army headquarters could run HICOM from Fort Bragg, NC. The two urban objectives along the route from the airfield to the beachhead could be established within perimeters enforced by military and civilian police to keep local civilians safe.

The exercise could be conducted in a LVC-integrated architecture (LVC-IA) and connected to a broader operation across CONUS. Another BCT from the 82nd Airborne Division could also execute a concurrent mission at JRTC, and the exercise originating from SAFB could facilitate JIIM training by including local, state, and federal law enforcement and emergency response partners.

Once the convergence window opens, the MAGTF, afloat in the Mississippi River aboard two medium landing ships (LSMs), would move to the beachhead objective.(38) Simultaneously, the airborne element, in flight on C-17 Globemaster IIIs, would approach the airfield objective. The 3rd Infantry Division’s air-land element begins loading onto C-5M Galaxy and C-17 Globemaster III aircraft at Hunter Army Airfield, GA. Over the next 24 hours, the JTF commander would synchronize the amphibious assault with the airfield seizure, expand the lodgment, and establish a GLOC from the beachhead to the airfield. The XVIII Airborne Corps would continue shaping the deep fight to enable its subordinate elements to support an eventual brigade-sized wet gap crossing in the LVC-IA.

Conclusion

Fighting LSCO in urban terrain is inevitable in the next fight. Bypassing urban areas will not always be an option. The Army must scale up its urban combat training to meet this challenge. The gap in large-scale, realistic urban combat training is a critical vulnerability. Mirroring the success of the JPMRC, the JET-PEUT could bridge this gap. By working through local partners to transform existing urban areas into dynamic, instrumented training environments, JET-PEUT could enable the Army to test MDO concepts, develop vital JIIM TTPs, and cultivate agile, adaptable division and corps staffs. While challenges in instrumentation and civil-military coordination are significant, they are not insurmountable. Instead, the difficulty involved in establishing JET-PEUT exercises could offer inherent training value. Embracing “Divisions in Concrete” alongside “Divisions in the Dirt” will increase readiness and help the Army and Joint Force win our nation’s wars.

Lastly, the JET-PEUT offers a different problem to train for and provides commanders with an avenue for innovative exercise design. As the Army continues its transition back to an Army of readiness for LSCO against a near-peer adversary — just like the Army of the 1980s was a purpose-built force designed to defeat the Soviet Union in the Fulda Gap, or Marshall’s Army was explicitly created to penetrate the Atlantic Wall and rid the world of Nazi tyranny — we need a capability to consistently train complex joint operations realistically to prepare for the next fight. Ultimately, in much the same way as the JPMRC provides combat-ready forces in theater, the JET-PEUT can provide combatant commanders with a large-scale, JIIM-qualified, urban-ready component.(39) The risk of inaction is too high. The increased readiness and lethality the JET-PEUT would provide the Army and joint community are absolutely worth the great efforts required to make it happen.

Notes

1 Field Manual (FM) 3-94, Armies, Corps, and Division Operations, 2021, para. 4-102; Todd South, “Divisions in the Dirt: The Army’s Plan for the Next Big War,” Army Times, 6 May 2024, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2024/05/06/divisions-in-the-dirt-the-armys-plan-for-the-next-big-war/.

2 “The Louisiana Maneuvers,” State of Louisiana National Guard, 24 May 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20070524090534/http://www.la.ngb.army.mil/dmh/immm_hist.htm; Robert Citino, PhD, “The Louisiana Maneuvers,” 11 July 2017, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/louisiana-maneuvers.

3 Jennifer McCardle, “Simulating War: Three Enduring Lessons from the Louisiana Maneuvers,” War on the Rocks, 17 March 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/03/simulating-war-three-enduring-lessons-from-the-louisiana-maneuvers/.

4 FM 100-5, Operations, August 1982, 1-3.

5 Anne W. Chapman, “The Origins and Development of the National Training Center, 1976-1984,” Fort Monroe, VA: Office of the Command Historian, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, 1992, 15.

6 Douglas W. Craft, “An Operational Analysis of the Persian Gulf War,” (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 31 August 1992), AD-A256 145.

7 David Vergun, “Pentagon Prioritizes Homeland Defense, Warfighting, Slashing Wasteful Spending,” U.S. Department of War, 9 February 2025, https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4060775/pentagon-prioritizes-homeland-defense-warfighting-slashing-wasteful-spending/; GEN Randy George and Hon. Dan Driscoll, Army Transformation Initiative Memo, 1 May 2025.

8 Michelle Tan,“‘We Will Be Ready’: George Describes His Focus Areas,” Association of the United States Army, 15 August 2023, https://www.ausa.org/articles/we-will-be-ready-george-describes-his-focus-areas.

9 Mark Pomerleau, “Army Updating Brigades Based on Results from Transforming-in-Contact 1.0,” DefenseScoop, 27 March 2025, https://defensescoop.com/2025/03/27/army-updating-brigades-transforming-in-contact-randy-george/.

10 FM 3-0, Operations, March 2025, para. 1-51.

11 Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-06/Marine Corps Tactical Publication 12-10B, Urban Operations, July 2022, D-1.

12 Kenneth K. Goedecke and William H. Putnam, “Urban Blind Spots: Gaps in Joint Force Combat Readiness,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, November 2019, 31-32, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/urban-blind-spots-gaps-joint-force-combat-readiness.

13 Russell W. Glenn, “Preparing for the Proven Inevitable: An Urban Operations Training Strategy for America’s Joint Force,” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2006), 107.

14 Office of the Under Secretary of War (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request, 4 April 2024, 3-11.

15 FY25 CTC Rotational Calendar, Combat Training Center Directorate (CTCD), Fort Leavenworth, KS.

16 Department of the Army Pamphlet 525-30, Army Strategic Readiness Assessment Procedures, June 2015, 33.

17 Corey L. Elliot, “Fighting the Future: Multi-Domain Military Operations Are Already Here. But What Is the Best Way to Prepare Ground Forces for this Reality?” (unpublished master’s degree thesis, University of Bologna, 2024).

18 Ibid., 53.

19 John Spencer and Liam Collins, “Urban Warfare Project Case Study #12 - Kyiv,” Modern War Institute at West Point, 21 February 2025, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/urban-warfare-project-case-study-12-battle-of-kyiv/.

20 Interview with Dan Billquist, Joint National Training Capability (JNTC) integrator/liaison to CTCD, U.S. Army Pacific Command (USARPAC) G3 Training, 21 May 2025.

21 Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi et al, “Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February – July 2022,” RUSI Special Report (London: Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, 2022), 24.

22 Ibid., 28.

23 Courtney Albon, “Palantir Wins Contract to Expand Access to Project Maven AI Tools,” C4ISRNet, 30 May 2024, https://www.c4isrnet.com/artificial-intelligence/2024/05/30/palantir-wins-contract-to-expand-access-to-project-maven-ai-tools/.

24 Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL), Lessons Learned from the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces: Command Post Survivability, No. 24-862 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Center for Army Lessons Learned, 2024), 1.

25 Ibid., 2.

26 MG Michelle M. Donahue, “The C2 Fix Initiative: What It Means for Sustainment Forces,” Army Sustainment (Winter 2025), https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Army-Sustainment/Army-Sustainment-Archive/ASPB-Winter-2025/The-C2-Fix-Initiative/.

27 See the Joint Pacific Multinational Readiness Center Overview Brief. POC: Mr. Scott Wilson, JPMRC Program Manager, G3T, USARPAC, 10 April 2025.

28 Ibid., 3.

29 Ibid., 5-7.

30 This point was discussed in detail during the author’s interview with MAJ Ryan Rothschild, Program Support Division Integration Chief, CTCD, and Mr. Billquist, JNTC integrator/liaison to CTCD, 4 April 2025.

31 Sarah Lee, “Electronic Warfare Innovations in Aerospace & Defense,” Number Analytics blog, 10 April 2024, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/electronic-warfare-innovations-aerospace-defense.

32 Interview with MAJ Rothschild and Mr. Billquist, 4 April 2025; also see Nokia’s description of the Banshee tactical radio: https://www.nokia.com/industries/defense/banshee-4g-tactical-radio/#key-features.

33 Department of Defense Instruction 1322.28, Realistic Military Training (RMT) Off Federal Real Property, 18 March 2013 (incorporating Change 3, effective 24 April 2020).

34 Ibid., 8.

35 This point was discussed during a phone interview on 3 April 25 with Brad White, chief of the O’Fallon Fire Department, O’Fallon, IL, and key POC for conducting training outside of Scott Air Force Base; author interview with MAJ Rothschild and Mr. Billquist, 4 April 2025.

36 Author interview with Mr. White; author interview with Mike Kolodzie, exercise planner, USARPAC, Fort Shafter, HI, via Microsoft Teams on 5 May 2025. For the CTCD, the author conducted an interview with MAJ Rothschild and Mr. Billquist, 4 April 2025. Author conducted a follow-up interview with Mr. Billquist on 21 May 25 at Fort Leavenworth.

37 For the definition of Military Operations Areas/General, see the Federal Aviation Administration’s website: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/pham_html/chap25_section_1.html.

38 This capability does not exist yet, though the program has moved into production. See Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Medium Landing Ship (LSM) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report R46374, 21 April 2025, https://crsreports.congress.gov for more information.

39 CGSC Learning Resource Center, Combined Arms Research Library, e-mail submission, 20 May 2025, reviewed for grammar, punctuation, and clarity of expression.

MAJ Elliot L. Corey is currently serving as the battalion operations officer for 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Stryker Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. His previous assignments include serving as commander of C Company, 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team (BCT), 82nd Airborne Division; chief of plans for 3/82 BCT; battalion S-4 for 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment, 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division; executive officer for A Company, 1-38 IN; scout platoon leader for 1-38 IN; and platoon leader in 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 4th ID. MAJ Corey earned a bachelor’s degree in government from Cornell University; he was selected as an Olmsted Scholar for the class of 2022. After learning Italian at the Defense Language Institute, he earned a master’s degree in political science from the University of Bologna (Bologna, Italy).

This article appears in the Winter 2025-2026 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of War or any element of it.

Social Sharing