For the last two decades, the CH-47 Chinook has dominated the counterinsurgency environment. Maneuver commanders value the platform for its versatility — not only as a cargo platform, but also as an air assault ship, rapid refueling asset, gun-slinging platform, and casualty evacuation ship when needed. Chinooks have provided ground commanders with rapid, flexible means to move mass. However, the uncontested skies of previous wars are no longer guaranteed. Army Aviation now faces future contested environments where U.S. air supremacy may not exist, and aircraft may not be able to participate in direct action. This shift presents an opportunity for the Chinook community to serve a new mission: directly supporting the sustainment commander.

The sustainment community faces a unique capability gap in future conflict. In an immature theater, Air Force air mobility assets like the C-130 must land closer to the theater sustainment command (TSC) in the joint security area (JSA). Air mobility needs runways, which provide adversaries with fixed targets, adversaries who can now use massed, cheap, one-way drones to cripple combat power. With this new reality, the time and space required to resupply a rapidly developing front will be extended to preserve air mobility combat power. This means that the Army must conduct resupply over unforgiving terrain against enemy action. To cross a river, convoys need a bridge. If the enemy removes that option, cargo is delayed, and the front suffers. Recent examples in the Russia-Ukraine War have provided striking lessons of what happens when maneuver elements cannot be resupplied. Between the JSA, corps support area, and division support area (DSA) is a commodity flow chokepoint that enemies can exploit to sever supply trains and reclaim U.S. territorial gains.

The lessons from Ukraine also pose a possible solution. The conflict has seen renewed contest over the air littoral. The lower air littoral, in this case 200 feet and below, is largely where Ukrainian and Russian helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles are forced to operate. This band of sky is too low to be effectively targeted by large anti-air assets and difficult for small arms to target. The solution is for sustainment commanders to own assets to exploit the air littoral in the rear while the theater matures to the point where air mobility can land closer to the forward line of own troops (FLOT). The answer is the Chinook.

Field Manual 3-04, Army Aviation, divides Army Aviation across three operational models: deep, close, and rear operations. All models have aviation assets working for the corps combatant commanders or below. While the need for heavy lift assets supporting maneuver commanders is critical, sustaining these forces is equally critical. Maneuver commanders need a blank check for ammunition, fuel, food, and Soldiers as they fight to mature the theater. Sustainment commanders in echelons above brigade (EAB) need the ability to rapidly shift the depth of magazine (the ammunition stockpile) to keep up with frontline demand.

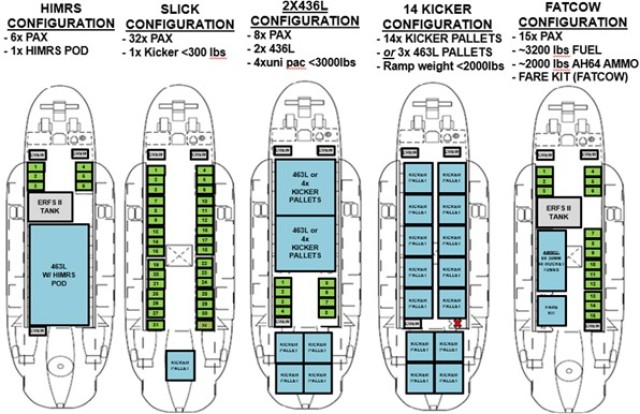

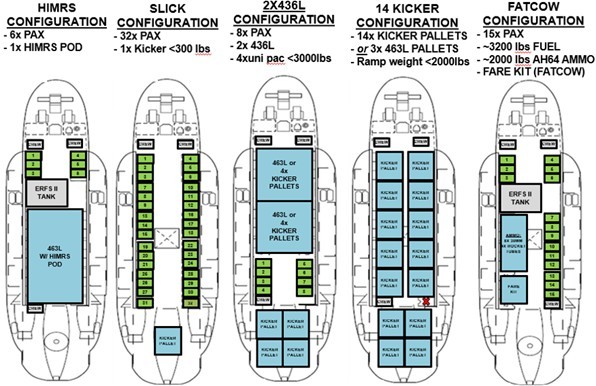

A single CH-47 can take as many pallets as a Container Roll-In/Out Platform (CROPS) or flatrack, though with more weight and dimension requirements. These pallets can be delivered anywhere, not just airfields. As DSAs and brigade support areas (BSAs) displace with maneuver elements, sustainment commanders at the operational level can use CH-47s to ensure commodity throughput and supply train continuity. It also means that DSAs and BSAs are not confined to areas with runways, which increases their survivability. As Role 1s and Role 2s become overwhelmed, these flights can provide immediate reverse-throughput of mass casualties to Role 3s.

Access to this tactical cargo asset can also help theater commanders by providing a layer of deception. While it might be obvious that a buildup of ammo and fuel indicates future combat operations, sustainment commanders can bank these commodities at the JSA by way of pre-made logistics package (LOGPAC) pallets. When the time comes to execute, pre-made pallets already sized to fit a CH-47 can be rapidly shifted around the battlefield to support the combat trains via tail-to-tails faster than enemy intelligence can track.

There are several advantages of keeping Chinooks in the backline with sustainment efforts. First, crews are closer to the folks who build the LOGPAC pallets. Non-rated crewmembers can ensure pallets fit the customer requirements with the Chinook limitations. As a downstream result, CH-47 units at the DSA receiving these pallets do not have to spend time sizing or rejecting pallets, which improves overall throughput.

As the FLOT extends farther from the TSC and the port, lines of communication become more vulnerable to attack from latent enemy units in the rear. This is how peer/near-peer adversaries plan to weaken U.S. campaigns. Retaining aerial reaction force assets behind the DSA can enable the rapid deployment of quick reaction force assets to sustain lines of communication to mitigate the threat.

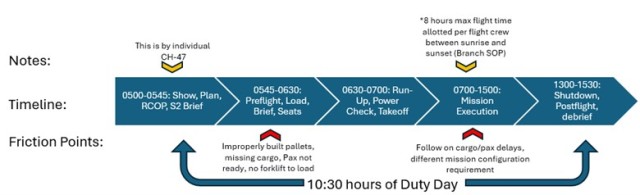

Crew rest is a limiting factor for CH-47 operations across the battlefield. The more maximum duty days and extensions crews get, the more worn out they become. This increases the Class A, B, and C accident rates. A CH-47 sustainment mission in the rear allows a better level of daily consistency and the ability to rotate crews to mitigate exhaustion.

Phase maintenance — routine inspections after set flight hours — adds further complexity. Aircraft that go into phase maintenance are rendered immobile and therefore vulnerable. The best option would be to have multiple phase lanes in the JSA. The maintenance, maintenance test flights, phase throughput, and theater aircraft rotation can be managed by Chinook units in the rear. Aircraft close to phase can be rotated to the rear and exchanged for fresh aircraft. Sustainment commanders can maximize the hours on low-time aircraft more consistently and predictably to control when an aircraft drops.

As the FLOT pushes forward and enemy anti-air capabilities degrade, the theater matures. This coincides with increased need for CH-47 capabilities at the maneuver corps and division levels to exploit the fractures in enemy lines. Because some CH-47 combat power has been used in the rear up to this point, fresh combat power can be surged as needed. Additionally, with the maturation of the combat theater, air mobility can get closer to the FLOT. As this happens, more CH-47s can hand off the sustainment mission to join the front. Table 1 is a theoretical breakdown of how to shift Chinook assets by theater maturation and what is gained by doing it.

To make this maneuver-sustainment ecosystem work, several actions must be taken before the next conflict.

First, the Logistics Captains Career Course must be offered to aviation officers rated in the CH-47. This would offer three advantages. One, CH-47 commanders would develop a background in the sustainment paradigm, becoming better able to integrate CH-47 units with EABs executing the sustainment mission. Two, this would improve the logistical expertise within combat aviation brigades because these officers are uniquely equipped to serve as battalion and brigade S-4s. Three, it would integrate the overall force by developing cross-branch relationships among junior staff officers and allow CH-47 officers to meet their future primary customers.

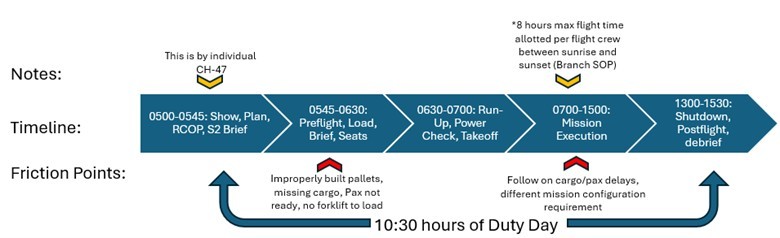

Second, we must increase personnel in the support operations mobility shops, specifically for the purpose of solving points of friction. This would be a low-cost change. These would be CH-47 non-rated crew members. Teams would move around the theater, identify inefficiencies in the CH-47 supply train, and work to fix them. For example, if LOGPAC pallets were built to go on a CROPS, but the ground train were disrupted, these teams could reconfigure pallets for Chinooks. The teams could also work with Chinook units at the DSA or BSA to improve systems and processes in the rear.

Third, we must start detailing Chinook companies to sustainment commanders to define their operational niche. This would be another low-cost change. Should they be a direct asset for expeditionary sustainment commanders? Would they work better as an independent rear-oriented theater taskforce? As a point of order, any Army sustainment unit that adopts Chinooks as an asset must be supplied with 463L pallets for improved cargo flow.

Since the 1960s, the CH-47 Chinook has been helping warfighters win wars. Its legacy is one of excellence. Its continued excellence may lie in supporting the sustainment paradigm through air littoral exploitation. While current conversations surround drones, artificial intelligence, and the next generation of warfare increasing levels of airspace denial, there is at least one thing that will not change: Soldiers will still need to take and hold ground, and those Soldiers will need beans, bullets, and bandages to be successful. The Chinook’s future lies in serving these Soldiers.

(Editor’s Note: This article is the winner of the ASU Writing Competition for fall 2025.)

--------------------

CPT Christopher Wise serves as the commander of Company B of 3-126th General Support Aviation Battalion in the Maryland Army National Guard. He previously served as a flight platoon leader of the 3rd Battalion, 126th Aviation Regiment and battalion S-4 of the 1st Battalion, 224th Aviation Regiment, in the Maryland Army National Guard. He served as a CH-47 detachment OIC in support of the 185th Expeditionary Combat Aviation Brigade mission during Operation Inherent Resolve. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Aviation Branch, and a graduate of Army Flight School and the CH-47 Maintenance Test Pilot School. He is currently a student in the Reserve Logistics Captains Career Course at Fort Lee, Virginia. He is currently a graduate student in the Master of Public Health program at Johns Hopkins University.

--------------------

This article was published in the fall 2025 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Social Sharing