June 6, 1889, began the way most tragic days do – on a beautiful sunny day that reveals no hint of pending destruction. This is how morning greeted the residents of Seattle on that day 125 years ago.

At 2:15 p.m. in Clairmont’s wood working shop (1st Avenue & Madison Street), John Back was heating glue over a gasoline fire. The glue began to boil over and dripped onto the floor below covered by wood chips and turpentine. Mr. Back did what most of us would do in that situation - he threw cold water onto the blaze that had started, which unfortunately only spread the fire. Within minutes, all the occupants fled from the building and the fire was quickly out of control.

The fire swiftly spread to the Dietz & Mayer Liquor Store, which exploded, then to the Crystal Palace Saloon, and the Opera House Saloon. Fueled by alcohol, the entire block from Madison to Marion was on fire. Firefighters quickly responded but it was soon clear they had too little water to have much of an impact on the raging fire. In a cruel twist of fate, winds were blowing out of the northwest fanning the flames as the fire moved south. Not even brick buildings were immune; the fire engulfed everything in its path and was rapidly growing.

Seattle Mayor Robert Moran relieved the acting fire chief and took command of firefighting efforts. At 4 p.m., he ordered the buildings immediately south of the fire to be blown up in hopes of denying further fuel for the blaze. The explosions did not stop the fire, but they did spread flaming shrapnel to other buildings.

Amid the smoke, flame and explosions, residents grabbed whatever valuables they could to save them. According to one account, “The general confusion which prevailed, and the fact that valuable goods were piled up in the streets in all directions, emboldened thieves to such an extent that they commenced carrying away property boldly through the streets. In some cases, the thieves were discovered, and chase was given, and they were rescued from lynching only by the vigorous efforts of the police.”

Colonel J.C. Haines was a well-known Seattle lawyer and the commander of the 1st Regiment, National Guard of Washington headquartered in Seattle. By late afternoon, Haines knew that nothing could be done to stop the fire, but he also knew without civil order there would be nothing to stop human nature. In his report to the Adjutant General, Haines wrote:

“It became apparent to me that nothing but the presence of the Military force, at least during the night, would avert pillage robbery, and probably graver crimes, and I accordingly, at about five o'clock, went to Mayor Moran and tendered him the services of the three companies stationed at Seattle for the purpose of assisting the civil authorities in the protection of life and property and the preservation of the public peace. My offer was gladly received by him and requested me to order them out and place them on duty as speedily as possible.”

In an act reminiscent of Paul Revere, Haines put on his uniform and rode through the streets of Seattle calling all members of the National Guard to immediately report to the armory for duty. Haines observed the following:

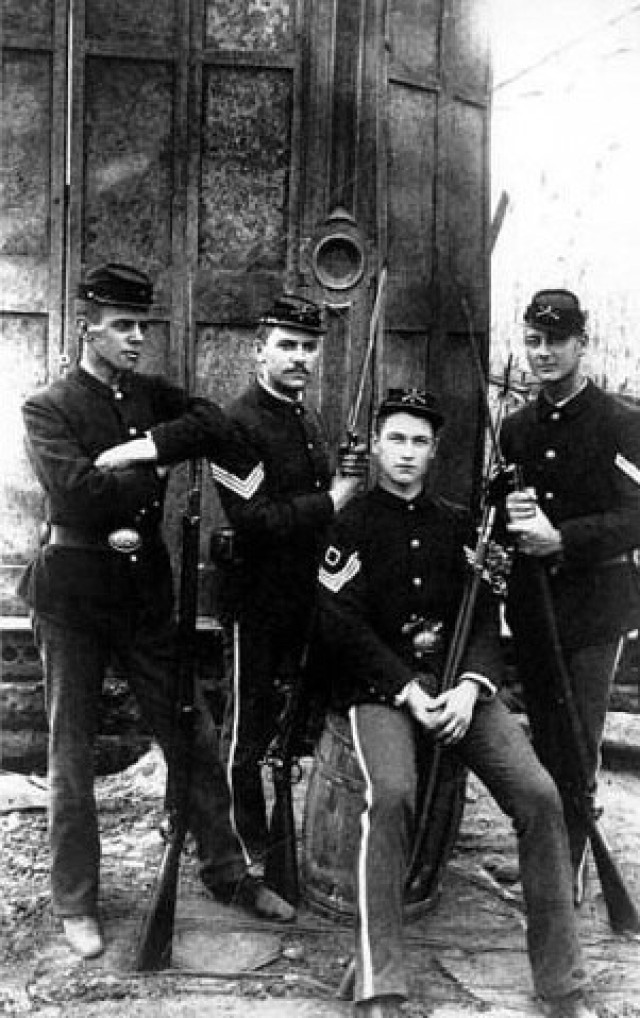

“Men left their property which they were engaged in saving, came immediately to the Armory, put on their uniforms, and fell Into line without thought of anything save obedience to orders. I do not think that there was a man in the three companies, then ordered out, who was not a loser by the fire and who had interests which most pressingly demanded his presence and attention, but there was not a murmur, not an application for an excuse, and at eight o'clock fully one hundred men had reported at the Armory for duty.”

The mayor ordered a curfew to maintain order, and 1st Regiment enforced it. Many of the men from the 1st Regiment were already exhausted from fighting the fire earlier in the day as volunteer firefighters and citizens, but now found the fortitude to stand their post throughout the night and into the next several days.

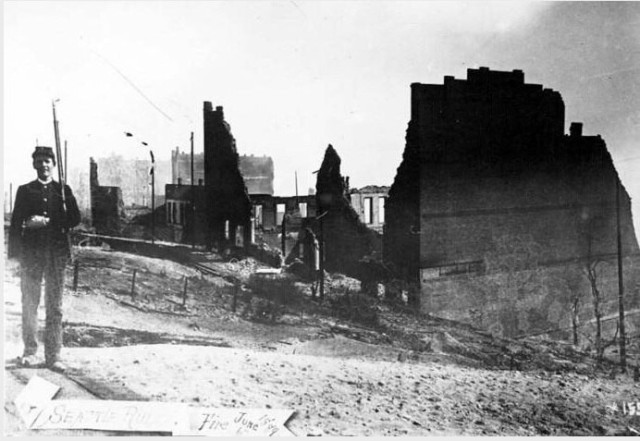

When the fire had finally burned itself out the next morning, much of Seattle lay in ruins. The fire had destroyed 120 acres (25 city blocks) of downtown Seattle. According to Haines, not a single building that was in the fire’s path remained standing. Amid the ruin, the 1st Regiment maintained order amidst the smoke, ash and heat of the day.

The Seattle Armory also became a key resource in the wake of the fire. The mayor established his headquarters at the armory, and prisoners from the jail had to be temporarily transferred to the armory.

“So threatening did some of the prisoners become that it became necessary for me to order the Company guarding them to shoot any one of the prisoners who attempted to break through their line after being challenged and halted. This order was given in the presence of the prisoners, and they immediately quieted down and remained in their places,” said Haines.

In the days after the fire, the armory became a soup kitchen for the multitudes of homeless and displaced residents.

“During this period as many as nine thousand meals a day were furnished at all hours of the day and night,” wrote Haines. The Armory was filled with people who slept there during the night, including in their numbers many women and children. Tables were set in the drill hall of the Armory and all who applied for meals were provided with them under the direction of the Commissary.”

Unfortunately, not all the citizens were eager to help the cause. In an area the 1st Regiment had secured and later pulled back from, a mob of opportunistic looters had descended upon the rubble to take whatever they could find. Property owners pleaded with the mayor and Haines to re-secure the area, which the mayor gave the order to do. Haines sent one of his companies:

“At this time there was a crowd of at least five thousand people within a radius of a dozen blocks in the heart of what had been the business part of the city. Many of them refused to move at the approach of the skirmishers, using insolent language and threats of resistance. Upon the approach, however, of the reserve they gave way, and upon seeing Lieut. Walsh with his men coming up Second street, at double time, they broke and many of them fled precipitately out of the burnt district and scattered along through Second and Third streets.”

Under Haines’ command, the 1st Regiment continued to maintain order, protect property, ensure the continuity of government and assist managing the humanitarian crisis caused by the fire. The other cities of the Washington Territory rallied around Seattle and quickly sent food, supplies and money. On June 19, 1889, civil authorities were able to resume control unassisted and on June 20, the 1st Regiment was demobilized from duty.

Haines summed up the performance of his citizen-soldiers by saying, “The National Guard of Washington has demonstrated that its members are gentlemen and soldiers, and that in them the people can always repose the fullest and most complete trust, and that no emergency can be so great or so sudden that it will not find them ready and able to meet it.”

Story written by Keith Kosik, Washington National Guard

Social Sharing