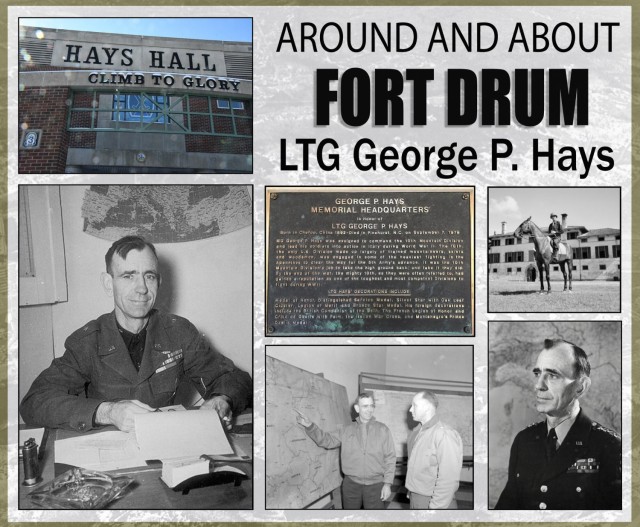

FORT DRUM, N.Y. (Sept. 15, 2022) -- Hays Hall, the 10th Mountain Division (LI) and Fort Drum headquarters building, is named after the division commander who led the original mountain troopers through the battles of Riva Ridge, Mount Belvedere and Po River Valley in Italy during World War II.

George Price Hays was born Sept. 27, 1892, in Chefoo, China. His parents, George and Frances Corbett Hays, served overseas as Presbyterian missionaries before they moved to Minnesota to lead a church ministry.

Hays, the fourth of seven children, graduated from high school in El Reno, Oklahoma, and attended Oklahoma A&M College (now Oklahoma State University) to study engineering.

While in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program in 1917, Hays was accepted into the three-month First Officers’ Training Corps at Fort Roots, Arkansas. After several weeks of basic training and infantry instruction, cadets could apply for branch commissions. In his memoirs, Hays wrote:

“It so happened that the day we were to make a decision on which branch we wished to join, was the day the Infantry schedule called for a 12-mile march with full pack, which weighed in the neighborhood of 60 pounds. The weather was hot and humid and the return march up the long hill in July heat and humidity was most unpleasant. Up to that time I had planned to remain with the Infantry, but I decided to apply for the field artillery and was transferred to the third battery which was being organized.”

Before completing the training camp, Hays applied for a direct commission in the Regular Army because he thought it would get him overseas faster than a commission in the Reserves. He received orders to join the 10th Field Artillery Regiment, stationed at Douglas, Arizona. The unit had a full complement of enlisted men, artillery equipment and horses to mount cannons and draw caissons, but it was short on officers. Hays saw this as an opportunity to take on more responsibility and acquire experience.

He had a love of horses, which would serve him well during World War I. However, when the regiment received orders to proceed to the New York port of embarkation, Hays was left behind with an animal detachment of roughly 800 horses and mules.

Hays joined his regiment overseas on June 10, 1918, at Saint-Nazaire, France, but he arrived at the conclusion of unit training when Soldiers were preparing to leave for the front.

Serving as the 2nd Battalion, 10th Field Artillery Regiment liaison officer for the 30th Infantry, Hays was tasked with delivering communiques by horseback for the coordination of artillery counterattacks.

In the Second Battle of the Marne, on the morning of July 15, 1918, German artillery fire took out seven horses from under him during his runs. Hays managed to find one of the few live horses that survived the bombardment when another Soldier abandoned his steed to find cover from incoming rounds.

Hays continued his mission late into the day until he was wounded and had to be evacuated. A shell piece glanced off his helmet, went through his gasmask and grazed his chest, but another piece went through the thigh of his right leg.

While recovering in a field hospital, Hays received a letter that the 7th Infantry commander sent to the 10th Field Artillery commander.

It read, in part: “Lt. Hays was wounded after his work was finished. I was very glad to see him wounded as I thought he would be killed and we did not want to lose him after his very fine work. The importance of perfect liaison of the 30th Infantry and 10th Field Artillery during this German attack, which was one of the greatest of the war, should be given great prominence as I believe it to have been a vital factor in the repulse of the Germans who made their principal drive through our sector.”

Despite his injuries, Hays joined the Meuse-Argonne offensive in late September. Several months after the Armistice, his unit was ordered home in August 1919. Hays, however, managed to get stationed in London, England, to help settle affairs of the American Expeditionary Force, which included settling small claims and disposing of warehouse goods to be sold.

While there, Hays married Gladys Stepto, the daughter of a British Army officer.

Hays received the Medal of Honor for his actions in France, as well as the Purple Heart, the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre with Palm. He was also knighted by the British.

He returned to the U.S. in December 1919 and went to Camp Pike, Arkansas, where the 10th Field Artillery was stationed.

Hays’ post-war assignments included the Command General Staff School, the Army War College and the General Staff War Plans Department. He was assigned to Cornell University for four years of ROTC duty. Hays also took field commands with various artillery units until World War II broke out in Europe.

As brigadier general, Hays served as commander of the 2nd Infantry Division Artillery in 1944, which was transported to Northern Ireland as part of the European invasion force. He temporarily became the 34th Infantry Division’s artillery commander when the senior officer was wounded, and Hays led the capture of Monte Cassino.

After returning to the 2nd Infantry Division, Hays went ashore on Omaha Beach on June 7, 1944, behind First Army’s 1st Infantry Division. He wrote:

“As we approached the shore I noticed that our craft was making for the wrong beach, for Utah instead of Omaha. I told the skipper where to land at Omaha. He said hostile artillery fire was falling on Omaha Beach so he planned to land us at Utah instead. I said I would not permit anyone to disembark on the wrong Beach, so I persuaded him to take us to Omaha where we belonged.”

They got ashore without casualties, but Hays’ 2nd Infantry Division troops encountered three weeks of heavy fighting to secure Brest and captured thousands of prisoners. The unit replaced 4th Infantry Division at the German Siegfried Line, and they were involved in the Battle of the Bulge.

The battle-hardened commander was promoted to major general, and then he assumed command of the 10th Mountain Division while the troops were completing their training at Camp Swift, Texas. His first order of business was to assemble the Soldiers in the field house so they could have a look at their new commander.

Hays was credited with improving troop morale with his positive attitude and a genuine concern for his Soldiers’ welfare. His pep talks encouraged esprit de corps whenever he circulated among formations.

In his memoirs, “The Journal of a U.S. Army Mountain Trooper in World War II,” H. Robert Krear wrote about Hays:

“We learned that he was a Medal of Honor winner in World War I, and apparently he quickly learned that the Tenth Division was something special. He obtained for us the Mountain Insignia that we had been wanting for so long (a source of great pride for the men); he trained us as a division for the first time; and division morale, which had sunk very low, was soon again on the upswing.”

Hays flew to Naples on Jan. 8, 1945, and met with Lt. Gen. Lucian Truscott Jr., commander of the Fifth Army and all U.S. forces in Italy. The 10th would be attached to IV Corps.

Facing the Allies was the Gothic Line, snaking 200 miles across Italy through the rugged Apennine Mountains south of the Po River Valley. The 10th Mountain Division was needed to seize Mount Belvedere, a key to the German defenses providing observation over one of the two main routes entering the Po Valley.

But first, they needed to secure Riva Ridge to deny enemy artillery observation of the objective. The ridge consisted of eight peaks from 3,200 to 6,000 feet high, and the Soldiers would attack at night. Hays opted to use a battalion of roughly 850 Soldiers for the initial attack on Riva Ridge, with another 180 in reserve to keep hold of it when the main body continued on to the Mount Belvedere assault.

On Feb. 16, 1945, two days before the attack was to commence, Hays discussed the plan with his troops. Dan Kennerly, with the 85th Mountain Infantry Regiment, wrote in his diary that the commander had such trust and confidence in his Soldiers that he was willing to speak on their level and openly share details of the campaign to come.

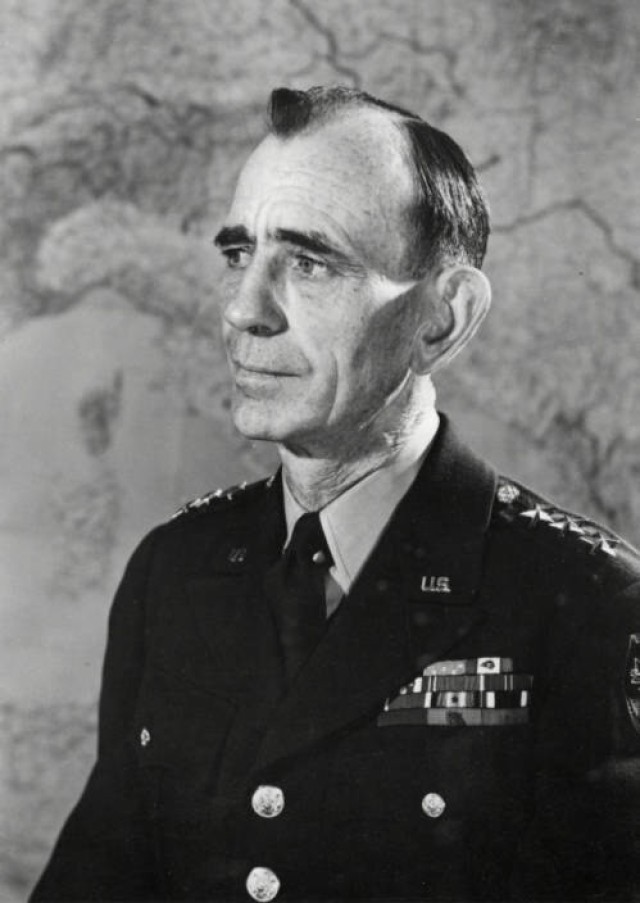

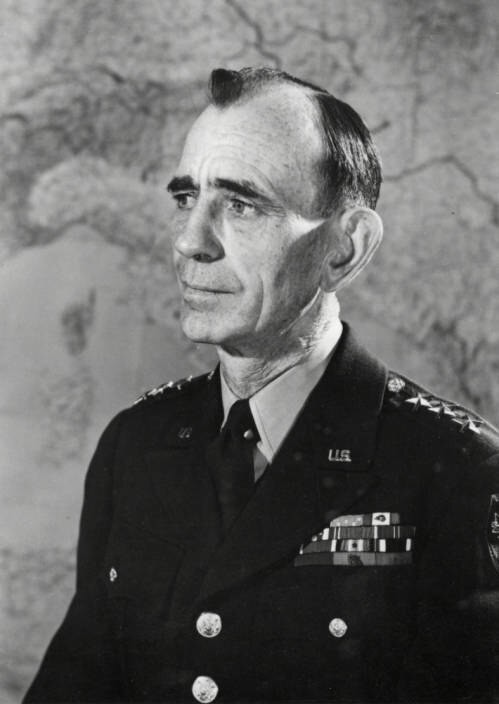

Kennerly also described Hays’ physical appearance at the time.

“He is not the way I would picture him. I figured him to be a pompous, old, pot-bellied, gray-headed man with his chest full of ribbons. He is completely the opposite. The general is not a large man. He has a wiry build with not an ounce of fat on him. His hair is black and thinning on top. His face is deeply lined, weather-beaten and tan. His head seems to be a little too large for his body. I believe he has the largest ears I have ever seen on a human. His eyes are dark and deep set. His looks remind me of an old, saddle-worn cowhand.”

Hays informed his troops that they would move up the mountains in silence – no supporting artillery or aerial bombardment, and weapons fixed with bayonets, but not loaded with ammunition. Hays did not want to lose the element of surprise.

Kennerly recalled Hays saying, “You must continue to move forward. Never stop. Always forward. Always forward. Always forward. If your buddy is wounded, don’t stop to help him. Continue to move forward. Don’t get pinned down. Never stop.”

Soldiers today live by the mantra, “Never leave a fallen Soldier behind,” but that was not protocol on this particular mission. Richard C. Johnson recalled in an oral history (transcribed on the Veterans History Project website) what happened when a platoon sergeant stepped on a mine.

“I had to do what General Hays said, ‘Leave him for the medics – don’t stop to take care of him.’ That was one of the hardest things I had to do, tell the rest of the company, ‘Come on, let’s go,’ and leave him,” Johnson said.

Not a single Soldier died during the actual climbs of the ridge, but 21 were killed in counterattacks. Hays wrote: “The prisoners we took were from German Alpine troops, reported to be their best troops. When questioned they said they thought the ridge was too steep to climb and did not expect an attack. The capture of Riva Ridge gave a great boost to the morale of all the troops and confidence that their night attack on Mount Belvedere would also be successful.”

By the time Mount Belvedere was secured, the division had sustained 926 casualties. Hays’ superiors thought it would have taken two weeks – not five days – to complete the objectives, with triple the number of casualties.

The 10th Mountain Division then set the stage for the final Allied offensive in Italy when they spearheaded the drive through the Apennines and raced across the Po River Valley to be the first troops into the Austrian Alps.

After the German ground forces surrendered unconditionally to the Allies in Italy, Hays escorted Gen. Fridolin von Senger, XIV Panzer Corps commander, to Allied headquarters in Florence where the surrender was made official. Von Senger, a Rhodes Scholar who spoke fluent English, informed Hays that when the 10th Mountain Division broke through two of his German Panzer corps, he had to swim across the Po with his troops the same day as the 10th crossed by assault boats.

Von Senger would later write: “Hays escorted me in his large Packard, and we exchanged our impressions of past fighting in which his division had been my most dangerous opponent.”

When the war in Europe was over, division Soldiers conducted occupation duty for several weeks until they received orders to return to the U.S. When they reassembled at Camp Carson, Colorado, Hays was ordered to inactivate his division in November 1945.

Hays served as commander of 4th Infantry Division at Camp Butner, North Carolina, which he also inactivated. He served as deputy commander of the 6th Army, and then acting commander after Gen. Joseph Stilwell died. Hays became deputy high commissioner to the Army of Occupation of Germany in 1947. Although he knew nothing about military governments, Hays was fascinated by the diversity of duties.

In 1952, Hays was assigned command of all U.S. forces in Austria – his final military assignment before retirement. On April 30, 1953, a farewell review was conducted for the 60-year-old lieutenant general in Salzburg to celebrate his 36-year career.

At the ceremony, Hays said: “I bear with me the experience of five and one half years in Europe. Years during which the nations of the free world have, by banding together, largely dispelled the uncertainty, fear, depression and panic that engulfed this continent five years ago. This policy must be continued. Our Army must be prepared and our soldiers must be alert.”

Hays managed to stay connected with the 10th Mountain Division in his retirement. In 1959, he spoke at a monument dedication at Tennessee Pass, near Camp Hale, Colorado, to commemorate those who were killed in Italy. Hays traveled to Italy with other veterans in 1963, where he conducted a historical review of the 10th Mountain Division’s first combat experience on Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere.

In 1975, Hays attended the reunion of the National Association of the 10th Mountain Division in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and he later attended a Memorial Day service at the Tennessee Pass monument.

Hays died on Sept. 7, 1978, at the age of 85, in his Pinehurst, North Carolina, home. He was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

Construction on the 10th Mountain Division and Fort Drum headquarters, Bldg. 10000, took two years to complete and at a cost of nearly $10 million. Division and Fort Drum agencies began relocating into the new facility in July 1990, and a dedication ceremony was conducted in September 1990. It was originally called the Division Command and Control Facility until it was memorialized as Hays Hall.

Social Sharing