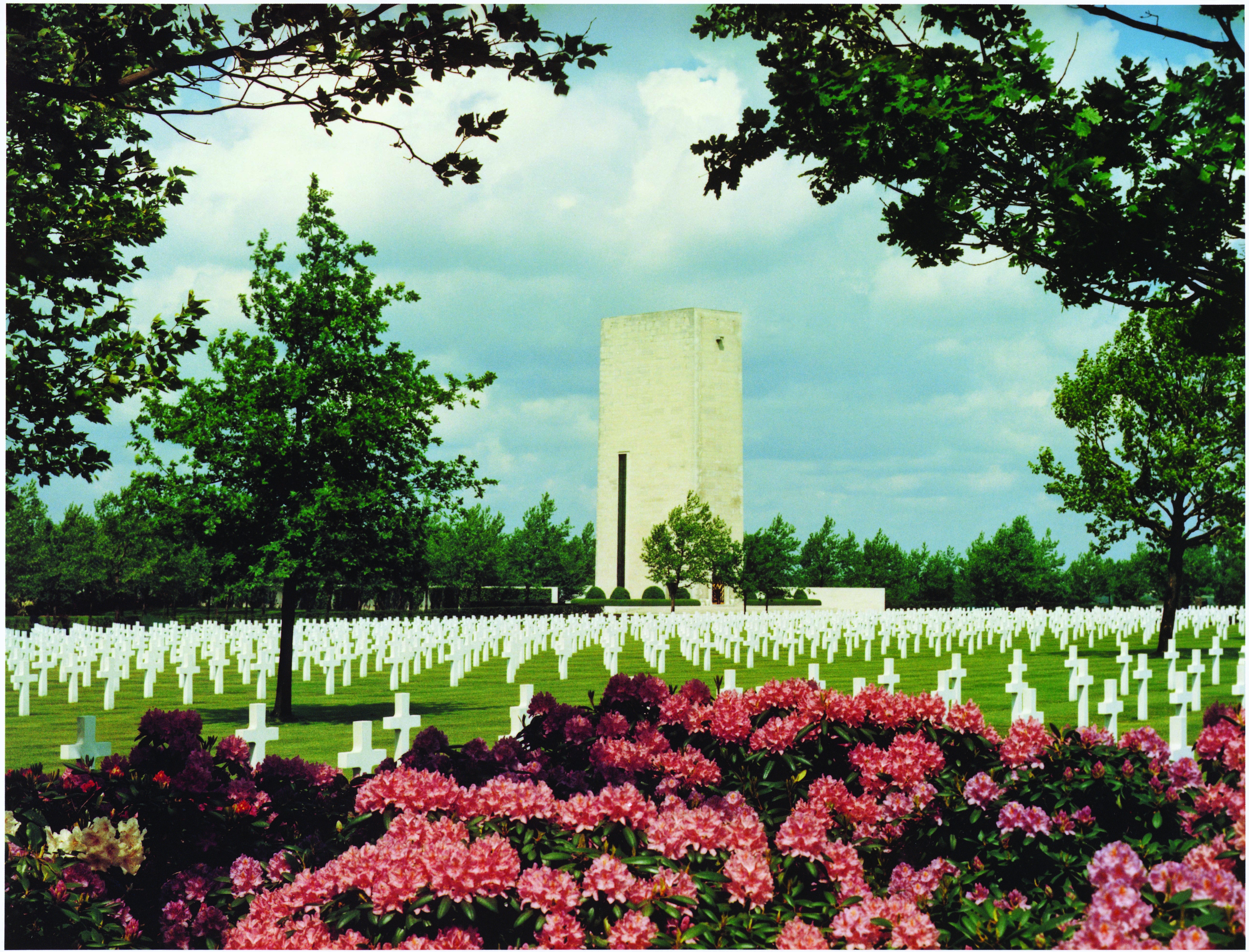

The Netherlands American Cemetery, nestled in the small village of Margraten, is an extraordinary place. One glance at its regimented and precise appearance conjures up an ethereal formation of Soldiers standing at attention before their headstones.

But that's just a small sample of what these departed Soldiers have in common. First, they voluntarily served their country in time of war. Second, despite their diverse backgrounds, they quickly discovered it didn't matter with whom they shared a last pair of socks, cigarettes or a sleeping bag in a foxhole: they just needed to stay warm and tell stories of home. More importantly, these Soldiers stood bravely together facing horrific situations, forging a lasting brotherhood.

"So it's appropriate they're still together," said Sgt. 1st Class Steve Mrozek, a former 82nd Airborne Division historian. "This is the definitive measure of Soldier camaraderie."

As a servicemember who has dedicated much of his life to helping veterans reconstruct their World War II pasts, Mrozek understands the importance of the Netherlands Cemetery. This landmark was one of the first he included on the "must see" list of battlefield tours for veterans returning to visit the Operation Market Garden and Battle of the Bulge areas.

"It's so rewarding to escort a veteran to a place that had so much impact on his life," said Mrozek. "Especially when there's an emotional attachment because it's hallowed ground for them."

As the only American military burial ground in Holland, stateside visits at the Netherlands Cemetery were rare, and Mrozek was determined not to let that happen on his tour.

A skilled paratrooper with 95 jumps and a recipient of wings from Great Britain, Canada and Holland, Mrozek also possesses a deep affection for the airborne GIs buried overseas. As a Soldier he felt it his duty to pay his respects to GIs who weren't just statistics, but courageous young men denied the chance for long lives.

Mrozek's passion for Operation Market Garden began with a re-enactment jump on the 55th anniversary of the Holland invasion. Flying over the Netherlands in a C-47 escorted by a British Spitfire, Mrozek wore the standard World War II paratrooper uniform and even carried a Thompson submachine gun. As the designated squad leader, he sat in the middle of the stick eagerly waiting the approach to the drop zone marked at 1,000 feet.

The second the green light appeared, Mrozek made his jump. After landing, he quickly discarded his chute and headed to his rally point.

"That has to be the most incredible experience I've ever had," grinned Mrozek, reliving the moment.

A carillon atop the 101-foot memorial tower chimed "God Bless America" and "America the Beautiful" the day Mrozek arrived at the Netherlands Cemetery. He paused to look at the left and right walls where the names of the significant battles fought were commemorated:

MAASTRICT*EINDHOVEN*NIJMEGEN*ARNHEM*JULICH*LINNIC*

GEILENKIRCHEN*KREFELD*VENLO*RHIENBERG*COLOGNE*WESEL*RUHR

Examining the Court of Honor, Mrozek discovered 1,722 names with rank, organization and state of origin; men killed in action in the region, but whose remains were never individually identified. Above the names, this message was carved:

HERE ARE RECORDED THE NAMES OF AMERICANS WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THEIR SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY AND WHO SLEEP IN UNKNOWN GRAVES

A chilly breeze accompanied Mrozek to the entrance of the burial site. Just beyond were the 8,302 Soldiers who had given their lives, mostly in the airborne, ground and air operations to liberate eastern Holland and advance into Germany over the Roer and Rhine rivers. He silently praised the mixture of Stars of David for the Jewish faith and Latin crosses for the others, arranged in parallel arcs that stretched over 65 acres.

Mrozek felt a powerful quiet as he passed the headstones that represented every state in the union, the District of Columbia, England, Canada and Mexico. The stillness intensified when he reached the 106 graves belonging to the unknowns and the 40 instances where two "brothers" lie side by side.

Each headstone provides rank, name, unit, state of origin and the Soldier's date of death. Just simple facts, but all Mrozek needed to identify with the fallen GIs in a small way.

Then, a chance look at the Registrar Roll in the Visitor's Building that stores information about the Soldiers in the Netherlands Cemetery presented a startling revelation.

"Private 1st Class, Paul G. Stinson. Plot K, Row 1, Grave number 15," read Mrozek eagerly. "Company A, 504th Parachute Infantry, 82nd Airborne Division."

Frantically, Mrozek searched for Stinson's gravestone, determined to find the Soldier he had come to know, thanks to a piece of World War II headgear. Minutes later he stood before the marker, almost in shock that Stinson was really there.

In low tones, Mrozek introduced himself to Stinson, saying how glad he was to meet him since records indicated the young Soldier had never received any visitors. Mrozek explained how he had acquired Stinson's helmet back in the mid-nineties and from the name, rank and four Army serial numbers stenciled inside, learned many details about the young GI destined to never return home.

Stinson was a 19-year-old private from California who was issued a recycled helmet, which meant he was in the 82nd only a short time. In fact, he was assigned just before Operation Market Garden began in September 1944.

At an annual paratrooper reunion a few years later, Mrozek happened to meet a veteran who remembered Stinson and knew of the accident that killed him on Oct. 27, 1944.

After he returned from a river crossing, Stinson went to retrieve his bedroll from a supply dump. While doing so, a Panzerfaust (German anti-tank weapon) hidden in the dump discharged, striking him in the stomach. Stinson was quickly taken to a house for shelter and given morphine for pain, but died soon after. The unit never found out how or why the German weapon happened to be there.

"Your platoon leader, 1st Lt. Reneau Brened, said you were a darn good Soldier," Mrozek told Stinson as he stood at the gravesite. "And that you were greatly missed."

The helmet stayed in the house where Stinson spent his last moments and worked its way to the attic where it was eventually discovered. After being passed around for some years, it was eventually picked up by Mrozek.

"So it was up there for maybe 50 years and now both the helmet and liner are with me. Learning what I did about him made it easier to talk to him. I let him know I was keeping the helmet for him, that someone was thinking of him, and that he wasn't forgotten."

Social Sharing