FORT BENNING, Ga., (June 3, 2015) -- Airborne School has been a part of daily life at Fort Benning for almost 75 years.

According to the Airborne website, it is a school that conducts basic paratrooper training for the U.S. armed forces, and is operated by the 1st Battalion, (Airborne), 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning. The purpose of the Basic Airborne Course is to qualify the student in the use of the parachute as a means of combat deployment, and that has been its mission since inception.

But where did the idea for Airborne Soldiers come from? How was it introduced to Fort Benning, and why does it matter 75 years later?

It all began in 1940 when the U.S. War Department approved the formation of an airborne "Test Platoon" under the direction and control of the Army's Infantry Branch.

This platoon was created after Gen. George C. Marshall, chief of staff of the Army, realized the potential for airborne forces - and mobilized his power to do something about it, according to A Combat History of American Airborne Forces.

Over 180 Soldiers, all from the 29th Infantry Regiment, volunteered to join the Test Platoon, said Sgt. 1st Class Paul Hart, 1st Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

"Imagine the mental capacity of these guys," Hart said. "(The officers) say 'we need you to volunteer to jump out of a plane at 1,500 feet with just a parachute. Oh, and we've never done it before - wanna give it a shot?'"

Out of the 180-plus Soldiers who volunteered, two officers and 48 enlisted men were chosen based on their high standards of health, fitness and a written test, said Master Sgt. Robert Lucas, 1st Bn. 507th Parachute Inf. Regt.

In World War II, most platoons had two officers in case one got hurt within the platoon and they needed an immediate backup, and extra men for the same reason. This was particularly important within the Test Platoon, as the risk for losing one officer was much higher.

"June 26, 1940, was the date that they actually stood up as the airborne Test Platoon," Lucas said. "That's when they came together and started training as a team."

The officer who took charge of the Test Platoon, Lt. William T. Ryder, had an interest in airborne and paratroopers long before the War Department approved the creation of a Test Platoon, according to Combat History. He passed the boards test with flying colors - walking out of the test room a full hour before any other candidate - and went on to become the Army's first paratrooper, a title he earned by being the first to jump out of the C-33 transport aircraft, said Luke V. Keating, historian for the 1st Bn. 507th Parachute Inf. Regt.

"Ryder was a huge factor in (creating) the training and jargon airborne still uses today," Lucas said. "He designed the 34 foot towers that still stand at the airborne training ground; his men called them 'Ryder's slide of death.' He also made every Soldier pack his own parachute, which he claimed inspired confidence in the paratroopers."

To prepare for the training jumps over Lawson Army Air Field, the Test Platoon flew to Fort Dix in New Jersey. Fort Dix had 150 foot jump towers, like the towers that stand on the airborne training field at Fort Benning today, only with two arms.

"The Test Platoon used the training towers so much that the military eventually bought four and they were built on Fort Benning in the early 40s," Hart said. "Ours have four arms, one in each cardinal direction, which the Army decided was good enough. Those towers still have the same elevators and same motors they did when they were built; the only updates are the electronics."

Although training has changed in small ways over the years, like the types of parachutes the Soldiers carry or the height of the towers they now jump from, the basics are still the same, said Keating.

"It is still five jumps to qualify. If a Soldier from the '40s came back to see Airborne school, there are certain aspects of it that they would truly recognize," Keating said. "The biggest difference is Soldiers no longer pack their own parachutes, and the biggest hurdle remains mind over matter - breaking their fear of heights."

The final and qualifying jump for the Test Platoon came August 29, 1940. The platoon did a mass exit jump and it went off with only a minor hitch: one paratrooper landed on a hangar, Lucas said.

"There were foreign army representatives there and many of them thought that Americans were so precise that during an attack they could plan to land a person on the top of a building," Lucas said. "So that worked out in our favor."

When it came to battle, the Test Platoon paved the way for future paratroopers and opened the U.S. Army to a whole new way of fighting - Soldiers who were both air-and-land capable; Infantrymen who could fly, according to Combat History.

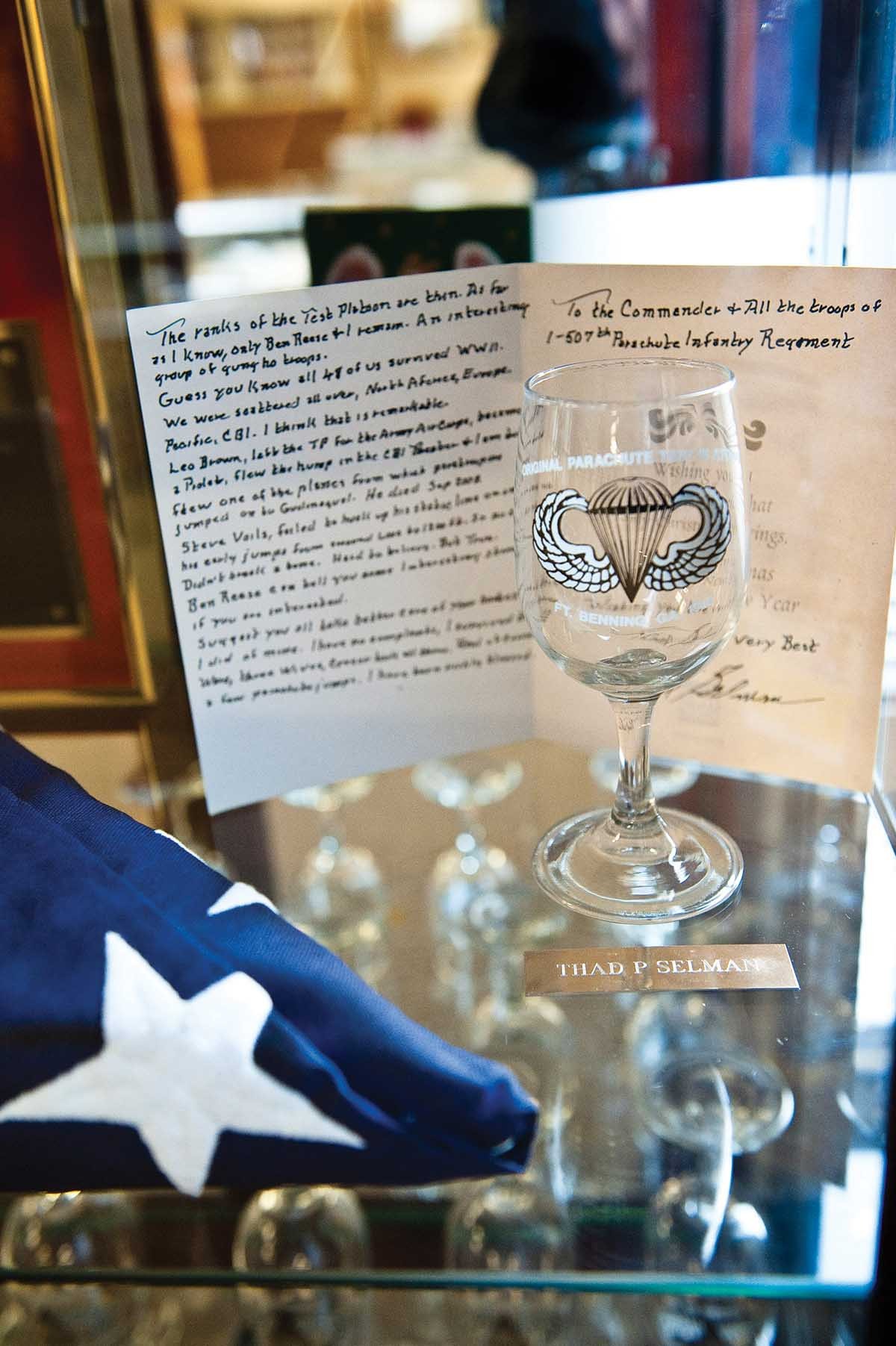

"Every one of them (the Test Platoon) was part of a legacy, and every one of them made it back from World War II," Keating said. "Out of the 50 soldiers who volunteered, all 50 came home from combat. None of them died in combat."

"Additionally, every member of the Test Platoon became training cadre for the Army's first parachute battalion, the 501st, and later the 502nd Airborne unit. The students became the masters," Keating said.

"As the 75th anniversary of the creating of airborne school approaches, and the anniversary of the qualifying jump does as well, we are going to hold a commemoration - we are going to jump again on to Lawson field," Lucas said. "We are inviting veterans to witness the jump 75 years later, and to remember how important those men were to the airborne we have today."

www.benning.army.mil/infantry/rtb/1-507th/airborne/

Social Sharing