Logisticians across Afghanistan are preparing for perhaps the most significant retrograde operation in the history of the U.S. Army. At the same time, they are mentoring the Afghan National Army (ANA) as it makes final adjustments to its logistics system. Retrograde is still in the beginning stages, but very soon strategic distribution hubs will be a flurry of activity while Afghan logisticians take on the responsibility of sustaining ANA contingency operations across their nation.

How will we measure our success? What key actions must we accomplish to achieve our desired end state? These questions keep the most visionary logisticians awake at night as they seek to posture their organizations for success.

The United States is not the first to attempt retrograde from Afghanistan while simultaneously mentoring ANA and Ministry of Defense logisticians. In his white paper, "After Ivan: Logistics, Population, Security, and LOCs [lines of communication] in Afghanistan 1989-1992," Dr. Austin Long notes, "The Soviets recognized very early that the war in Afghanistan was one of logistics, and attempted to build the sustainment capabilities of their Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA) allies."

The Soviets enjoyed moderate successes building an ANA logistics system while simultaneously retrograding. Indeed, the system the Soviets built lasted nearly three years after the departure of the Soviet Army. There is value in reviewing the Soviet's logistics experience in Afghanistan and using those lessons to inform our success.

ANA AFFINITY FOR THE SOVIET SYSTEM

When a U.S. Army mentor asks an ANA logistician why he is doing something a certain way, the response is usually, "That is the way the Russians taught us." The ANA still relies on Soviet logistics doctrine.

Using the Soviet doctrine, ANA logisticians do not analyze consumption factors using Microsoft Excel. In fact, the average ANA logistician does not comprehend the idea of an automated enterprise system. Rather, they conduct all transactions using pen and paper and record the transactions on ledgers. Subordinate organizations receive equal portions of commodities without respect to reorder points or customer wait time, and patronage is a societal norm.

The ANA sustained itself for nearly three years after the Soviet departure and only failed after the withdrawal of Soviet ministerial advisers and foreign aid. The Soviet system spoke to the Afghan workers. They remember it, and it makes sense to them.

The Soviet system lacks efficient accountability, but it can work and may serve as an incremental step in a more mature system. ANA logisticians will first need to begin conducting business practices in a common language and achieve a literacy rate higher than 30 percent in that common language. This will enhance the average ANA logistician's ability to comprehend systems and concepts that bring increased accountability and auditability.

PREPARING TO LEAVE

So where should Army logisticians focus their efforts in these final days? Improving readiness in ANA support battalions is important, but perhaps those support battalions should not be the strategic-level objective of our focus. After all, the ANA logisticians have illustrated a resiliency and ability to sustain their organizations when they absolutely have to. Considering that the Afghan failure came only after the loss of Soviet foreign aid and advisers, U.S. Department of Defense logisticians should seek to place competent logistics advisers at the Afghan Ministry of Defense. Ministerial-level advisers also should be placed at regional logistics support centers across Afghanistan. These individuals must understand receipt and distribution processes from the manufacturer to the user.

Although some of this is already being done, logisticians should recognize the significance of this goal as we move forward. Having the appropriate ministerial advisers, coupled with the appropriate measure of foreign aid, could afford the ANA logistics community the opportunity to continue to grow.

TACTICAL AND OPERATIONAL RETROGRADE

Soviet retrograde managers may not have adequately anticipated the effect of reduced LOC security during their retrograde. By 1988, Highway 7 through Nangarhar province had been interdicted by insurgents, and most secondary highways off Highways 1 and 7 were only passable as part of coordinated combat operations.

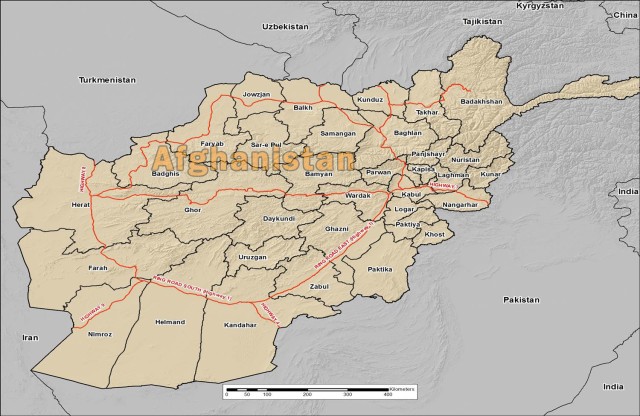

U.S. Army logisticians must consider the success of insurgents early in the Soviet withdrawal, assume there will be an effort to interdict U.S. LOCs, and focus retrograde and intelligence efforts on provinces like Paktika, Kunar, Khost, and Zabul. Logisticians must assume that retrograde from outposts far from Highway 1 will not necessarily occur before the retrograde of key locations along Highways 1 and 7. (See map of Afghanistan showing major highways at https://core.us.army.mil/content/images/2014/06/18/350544/size0.jpg.)

U.S. logisticians must plan for insurgent-led interdiction of LOCs as we retain more distant locations longer than those in closer proximity to our strategic bases. Logisticians will have to remain aware of ever-evolving operational decisions to leave some bases open longer than others, identify locations that will offer challenging retrograde options once LOCs are interdicted, and take action to mitigate the difficulties associated with the eventual retrograde of those locations.

RETROGRADING HARD TO REMOVE ITEMS

If U.S. Army logisticians are to leave less equipment in the battlespace than the Soviets did, what actions can they take now to foster a more synchronized retrograde once LOCs are interdicted? First, they must assume LOCs will be interdicted. Second, they must frame the problem through battlefield geometry informed by intelligence estimates that allow them to anticipate emerging hard-to-retrograde but longer lasting and more remote locations. Then, logisticians must start retrograding unneeded outsized cargo items exceeding sling-load weight limits and work with the maneuver community to reduce such places to an expeditionary equipping level.

Logisticians must prepare now for scenarios involving no ground retrograde options at locations with equipment that is over sling-load limits and consider disposition instructions for such equipment. The Army has done this in the past by dismantling outsized items and retrograding them by air in pieces or by staffing such items for destruction. If the goal is to leave no intact equipment like the Soviets did, with the exception of equipment that the Army is passing to the ANA, logisticians must begin planning now.

There is value in reviewing the Soviet logistics experience in Afghanistan. We can use Soviet lessons to identify some of the key tasks we must achieve if we are to avoid some of the failures the Soviets experienced. U.S. Army logisticians have much to accomplish in Afghanistan in a short time. If they are to be successful, they should focus some effort on retaining competent ministerial-level advisers beyond 2014, not only in Kabul but also throughout the country's regional logistics support centers.

The Army must resource intelligence estimates that afford an opportunity to anticipate insurgent-led LOC security interdiction at the tactical level. The soviet retrograde from Afghanistan was celebrated as a Soviet defeat in the American media; we should consider the successes and mistakes the Soviets made as we define our way ahead and shape the story of the U.S. forces' departure from Afghanistan.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Lt. Col. Matthew T. Hamilton is the commander of the Group Support Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne), currently deployed in support of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-Afghanistan. He holds a master's degree in executive policy management from Georgetown University and is a graduate of the Command and General Staff College.

Capt. Michael Brent Payne was the commander of the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Group Support Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group, and is currently the battalion S-4 for the 4th battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group. He holds a bachelor's degree in criminal justice from Kennesaw State University and is a graduate of the Combined Logistics Captains Career Course.

Chief Warrant Officer 2 David A. Holcomb Jr. is the senior electronic systems maintenance warrant officer for the Group Support Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group, and is currently deployed to Afghanistan as the partnership logistics officer-in-charge of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-Afghanistan. He holds an associate degree from Columbia Southern University. He is a graduate of the Warrant Officer Advanced Course and Support Operations Course Phase II.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the July-August 2014 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Browse July - August 2014 magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing