Advance, fight, suffer retreat -- it was the same old story for the U.S. Army, month after month, year after year, as the war dragged on with mounting casualties and no end in sight. Ever since the summer of 1861, Union forces had advanced into Virginia -- only to be blocked, parried, or outright defeated in battles immortalized with such names as First Bull Run, the Seven Days, Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Mine Run, late in 1863, was not even dignified with the name of "Battle;" that inglorious affair, so promising yet so unproductive, came to be branded a "Fiasco."

After such tactical and strategic defeats, the Yankees always fell back, sometimes to the protection of Fort Monroe or fortified Washington, more often behind the cover of the Rappahannock River and its main tributary, the Rapidan River, both of which ran from west to east across central Virginia.

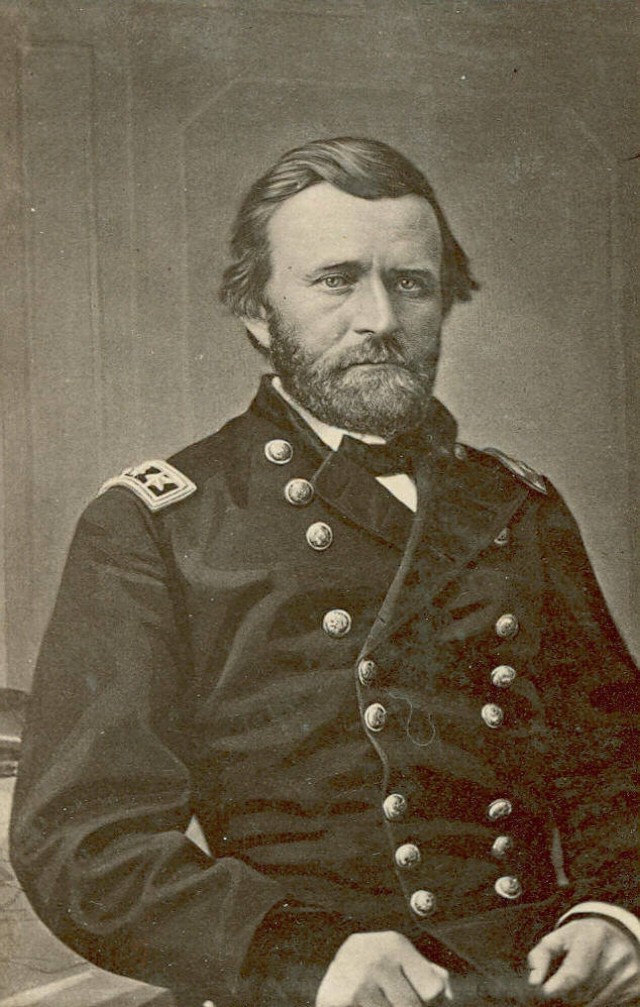

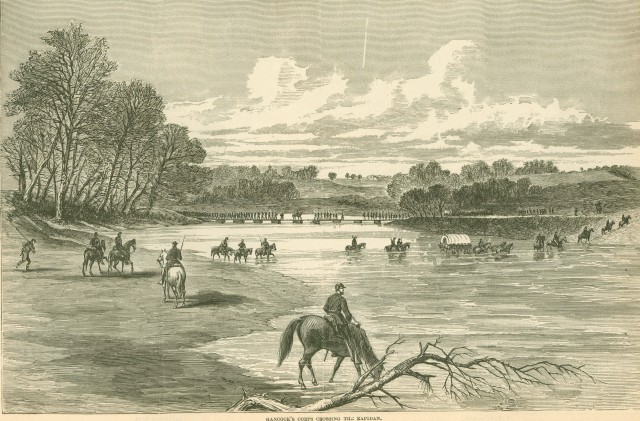

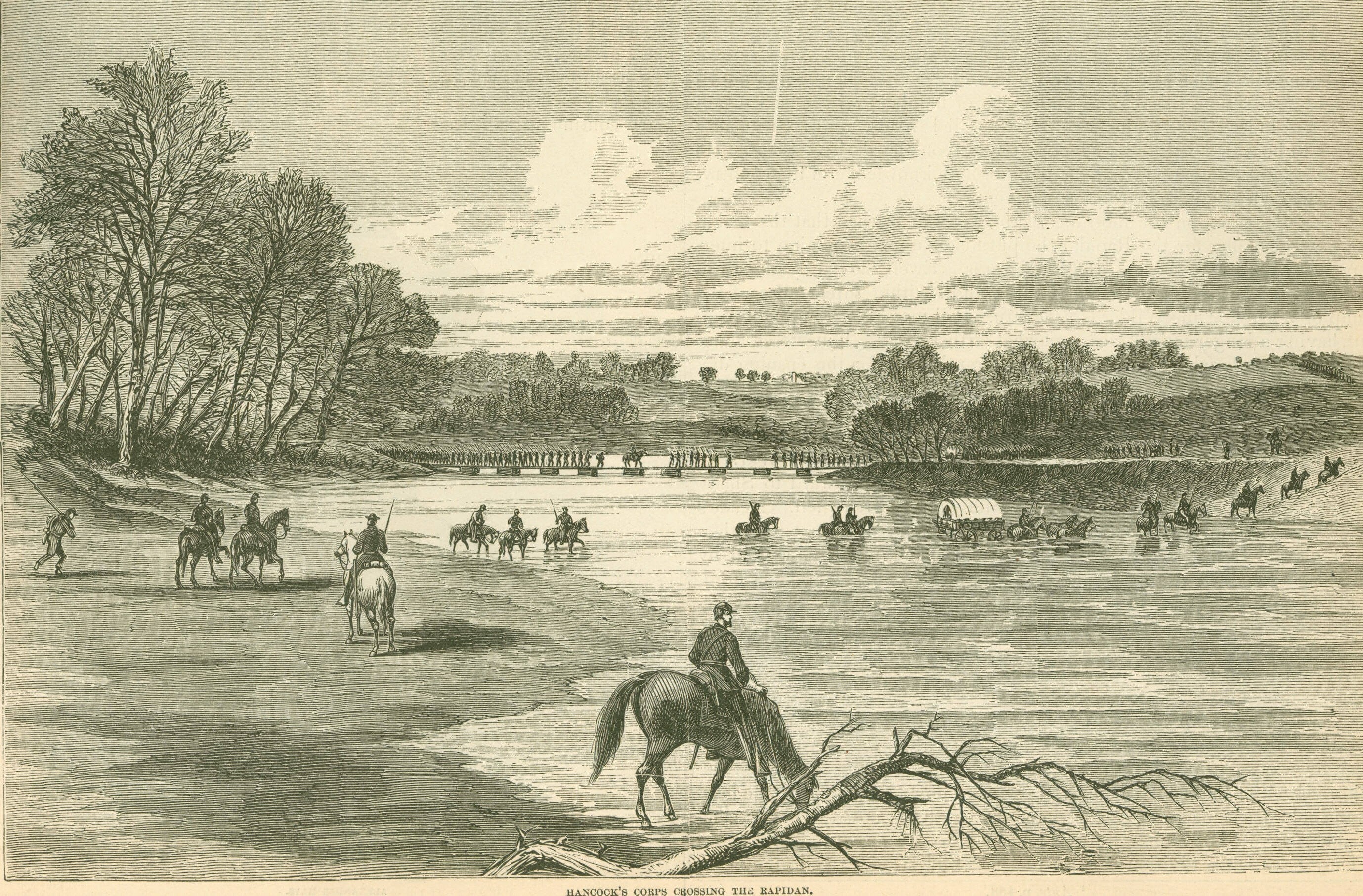

Following the Mine Run Fiasco, Federal forces wintered in Culpeper County, north of the Rapidan. In May, 1864, they again advanced across that stream, into Confederate country. The reorganized, reinforced Army of the Potomac led the way, under Major General George G. Meade, the national hero of Gettysburg. Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's independent IX Corps followed Meade. To coordinate both commands and oversee overall operations, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant accompanied this Virginia strike force. The captor of Fort Donelson, the victor of Vicksburg, the savior of Chattanooga, Grant had just been promoted General-in-Chief of the entire Union army in March of 1864. As not only the most senior but also the most successful Federal general, Grant chose not to return to the Western Theater but to take the field in the Old Dominion. There he would do battle directly against the best general and best combat command of the Confederacy: Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

Grant moved southeastward over the Rapidan, May 4. He hoped to hasten through the tangled Wilderness of Spotsylvania and bring the Butternuts to battle in more open country farther south. Lee, however, would not play that game. Rather than remain within his Mine Run fortifications or shift southward to Grant's preferred battlefield, Lee boldly struck eastward to catch the Bluecoats in the Wilderness. His advance left them no choice but to stop moving south and head west to meet the oncoming danger.

The ensuing Battle of the Wilderness raged May 5-6, 1864. Thickets, underbrush, and scrub growth, with few open fields, reduced Northern advantages of manpower and artillery. The difficult terrain also concealed Secessionist forces which delivered devastating attacks against both Yankee flanks. Two days of battle cost the Unionists over 17,000 casualties, the Graycoats more than 7,000.

Such disparity of losses implied Federal failure. Adding to that appearance was the tactical defeat, sooner or later, of every Northern attack. The Yankees' inability to get through the Wilderness without fighting strengthened the stigma of strategic stalemate. To cap off the calamity, the Bluecoats began pulling back on May 7, as if they were retreating across the Rappahannock -- yet again.

At first glance, the Battle of the Wilderness thus appeared the latest in a long line of operations in which a proud, confident Union army advanced into Confederate territory, only to suffer severe defeat and be compelled to retreat across the river. That the North's greatest general, Grant, should meet such a fate added to the gloom of an apparently unwinnable war.

But Grant was different. He had suffered setbacks throughout his Army career but had succeeded in spite of them. It would be the same this night of May 7-8, 1864. He was not retiring, after all, only disengaging in order to renew attacking elsewhere. Rather than retreat leftward over the Rappahannock, he turned rightward and resumed striking ever more deeply into Virginia and the Confederacy. The road ahead would prove long, bloody, and uncertain, marked by many memorable milestones like Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg. Undaunted, Ulysses Grant now took that road. It was a road which led to Appomattox -- and victory.

Social Sharing