Born June 2, 1931, in Monticello, Ga., William A. Connelly served in the U.S. Army more than 33 years. His career began as a National Guardsman in Americus, Ga., and he subsequently served in various positions worldwide as a tank crewman, tank commander, platoon sergeant and command sergeant major while on active-duty status from 1954 to 1983. During the Vietnam War, Connelly served as first sergeant from October 1969 to November 1970. His service included four tours in Europe as well as a tour in the Dominican Republic.

As the sixth sergeant major of the Army, Connelly witnessed many changes within the service as well as American society. He also contributed innumerably to the Army, effecting change on many different levels.

At 79 years old, he is still very active within the military community, attending various functions throughout the year, especially for the Association of the U.S. Army as well as the Nominative Sergeants Major and Senior Enlisted Advisor Conference held each year at the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy, Fort Bliss, Texas.

Recently, Connelly sat down to discuss his stellar career and issues that are close to his heart. "Magnanimous" seems to describe him perfectly, and his Southern charm, humor and modesty truly make him a treasure, as is apparent by the talk of the local community. "We are very proud to have the sergeant major here in Monticello," a local businessman said.

CAREER TRACK

"When I joined the Army, we didn't have a sergeant major of the Army, and I never heard that term until I was already a senior first sergeant," Connelly said.

The position was not established until 1966, when William O. Wooldridge was sworn in as the first SMA.

When Connelly first joined the National Guard in 1949, and then was drafted into active duty in 1954, he entered under the presumption to do his time and then get out. But, that turned into a long and lustrous career. Setting him apart from his contemporaries, he already had two years of college under his belt, catapulting many promotions rather quickly until the centralized selection process began in 1969.

After Basic Training and Advanced Individual Training, Connelly was held back so that he could help train others. Consequently, he became platoon sergeant and then first sergeant of the same training unit. "I thought it was a great job because I was not a 'diamond' first sergeant. I was an E-6," he said, adding that he was young and had "the least experience of anybody there." He would remain a first sergeant and operations sergeant for quite a while. "I'm the only guy I know to have gone through a 10-year war and not get promoted. I was a first sergeant when Vietnam started, and I was a first sergeant when it ended."

Connelly would go on to be the 7th Army Training Command Brigade sergeant major and from there was selected as 1st Armored Division sergeant major, then U.S. Army Forces Command sergeant major, ultimately reaching the pinnacle of the enlisted ranks - sergeant major of the Army from 1979 through 1983.

"I was in a leadership position the entire time I was in the Army, and my wife says I still think I'm in it," he joked. But good leaders, good noncommissioned officer leaders were a little scarce after the Korean and Vietnam Wars, he said.

MAJOR CHALLENGES

"I had a lot of challenges before I got to sergeant major of the Army," Connelly said. One of the challenges he refers to was enlisting qualified Soldiers after Korea and Vietnam. "When I became SMA, we had been having a problem with what my chief of staff termed a 'hollow army.'"

Connelly's chief of staff of the Army was Gen. Edward C. Meyer, whose term coincided with Connelly's own. Meyer once testified before Congress regarding the shortfall of qualified personnel throughout the Army. He termed the dilemma "hollow army" since retention rates were dismal, and many Soldiers at the time lacked formal education. Many served their required time and then left the Army, leaving more gaps in experienced leadership and training. Meyer went on to state in a 1994 report by the Defense Science Board Readiness Task Force that the military of the late 1970s and early 1980s were "hollow forces," and the Soldiers were not prepared to respond to most incidents without ample warning and preparation.

Connelly said neither the combat arms nor the Table of Organization and Equipment positions were fully filled. "Manning the force and retaining the force was a big challenge to my chief of staff. That was a challenge for the Army."

After realizing his vocation as a professional Soldier, Connelly knew he wanted an Army that was more selective. "I wanted an Army where more people were trying to get in it than we could take. The last two years as sergeant major of the Army, I was beginning to see that. We didn't have to accept every Soldier who wanted to join. We implemented certain criteria they had to meet, and we were more selective. The Army has continued to do that. I think right about then is when the Army started on the track of real professionalization of the Noncommissioned Officer Corps," he said.

But, Connelly refuses to take sole credit for the improvement. "When I left the Army, it was in much better shape than when I came in it, but not because I did anything. Manning the force with quality Soldiers was one of my major challenges. I did everything I knew to improve that. And I know Gen. Meyer and his staff - which I was a part of - I know we did a good job. And it's been carried on by every sergeant major of the Army since," he said.

RIBBONS

Soldiers can thank Connelly for four of the ribbons they pin to their dress uniforms. His subtle suggestion during a Department of the Army staff meeting contributed to the creation and authorization of four ribbons that most enlisted, first-term Soldiers pin on their chests.

"When it came my time [to speak], I said to the staff, 'In the Air Force, by the time an airman completes his AIT and spends three or four years in service, he or she could conceivably leave with two rows of ribbons. We [Army Soldiers] leave with the National Defense Ribbon, and if we've gone overseas then we may have gotten an Army Commendation Ribbon, which was very difficult to get in those days. It seems like we could have a ribbon for completing basic training and being awarded an MOS. We ought to have something between the Army Commendation Medal and the Bronze Star.' But, that's about all I said. I just planted the seed to the DA staff."

His seed planting led to the Army Cohesion and Stability Study in 1980, which established the Army Achievement Medal, Overseas Service Ribbon, Army Service Ribbon and the NCO Professional Development Ribbon. The Institute of Heraldry was commissioned to design the awards in April 1981.

"In about six months, those ribbons had been designed by TIOH. Every line, every color means something," he said, explaining that it wasn't just up to him to make the changes. "I know I was instrumental in it, but a sergeant major of the Army can't really do anything that the chief of staff doesn't support. So, I would like to think that I planted the seed."

Connelly explained that the ribbons and medals help with retaining Soldiers. "When a civilian out here sees a couple of rows of ribbons on a Soldier - they don't know what they're for, but they think it's for something. It's for something better than a good footlocker," he quipped.

VIETNAM

"I was first sergeant of Troop B, 9th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division. [The Army] had replaced the tank with the helicopter, which initially was a challenge for me since I had spent all my time in armor. Of course, I had never been in a helicopter except to go from point A to point B, very few times. I came off of civilian component duty from Georgia on a Thursday, and Friday morning with the change of time, I was being flown by helicopter to Quan Loi, Republic of Vietnam." Troop B would become one of the most highly decorated units in Vietnam, flying almost continuous combat missions.

"The helicopter had to fly around because it was being attacked by mortars, and they couldn't land. My unit was located in a rubber orchard in Quan Loi, and there was a larger unit there with us, the 29th Infantry Brigade. Somebody in our unit went to battle every day. There wasn't much I could do as far as going to battle with a helicopter, except fly scouts, and every time I tried that, I got sick."

Connelly spent a lot of time with the infantry platoon in his unit, even going out on missions with them. "Of course, I was responsible for everything when they came back from battle. The Army didn't send me there to be an infantryman; I was a first sergeant. I had to make sure we had water. I had to run the mess, maintenance - all that kind of took care of itself, because I had good NCOs. But the first sergeant is ultimately responsible. I went out on missions to gain their respect. That's what a good leader does; he shows his Soldiers he can do what they do."

Vietnam was a challenging 12 months, he said. "I didn't realize how much I enjoyed it until it was all over. It was a tough tour, and I saw a lot of combat. The unit I was in had a very high record of battle and battle streamers. Had a few people killed, had a lot of planes that crashed. A lot of them were in bad weather ... a challenging tour, as any combat tour is."

As history shows, when Soldiers returned from Vietnam, some were treated poorly by the public. "A lot of young people did a lot of fighting over there, and they lost a lot of comrades. But, when they came back, they couldn't get a job; they got on drugs. A lot of them experienced what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, but they didn't know what that was then. I had my problems with it, too."

Connelly said he was lucky that he had a family, a new house and a new first sergeant position at Fort Knox, Ky., when he came back. "I came back and got busy with moving my family and being a first sergeant with another unit. I had challenges that would not lend itself to me sitting around and thinking a lot about the war. But, I thought about it at times, and I still do. I sleep in a bed back here that's got safety railings on it," he said, pointing to a back bedroom down the hallway. "I still have a lot of nightmares."

As his voice grew quiet and eyes filled with tears, Connelly whispered, "I don't like to talk about that. I wouldn't give anything for the experience, but I certainly don't want to go through it again. War is hell, and I don't care what part of it you're in."

Those Soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan shouldn't be ashamed of serving. If they have a problem now, they can do something about it with the Army's help. The resources and facilities have improved, so Soldiers need to take advantage of the help, he advised.

Connelly said those Soldiers who have completed multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan have had it tougher than most, and the American public, Army and Department of Veterans Affairs need to do more for the returning Soldiers.

"We should take care of Soldiers because of the trauma they've been through. I'm glad I didn't have to come back to the states for 12 months and then go back over there. Some of these men and women are going back over there for the fourth and fifth time, and the law of averages begins to catch up with you. You're away from your family. I don't know how they stand it. And I think America should do everything it can to take care of Soldiers. We should monitor them; leaders should keep up with them when they come back and see to it that if they need help then they get it," he said.

Connelly knew of no other time that Soldiers were routinely engaged in combat for 12 to 15 months, came back home to stay a year or two and then go back. "It happened some in World War II and some in Vietnam but nothing like Iraq and Afghanistan."

WORDS OF WISDOM

The former SMA emphasizes training for new and experienced Soldiers. "If I can share anything without being emotional about it, it would be along the lines of, training never ends. You'll have to continue to train during the war, and when you come back, you know you're going to have to go again. Approach that training with diligence, and get prepared to go back over there. Every NCO has a tremendous responsibility to the people he or she is leading."

Connelly said Soldiers should know how to do one or two jobs ahead of their grade, because the time may come when they have to do it. "You got to know your job, the job ahead of you, and maybe the second one ahead of you, and be prepared to take over. Training never stops."

Some Soldiers came back from Vietnam thinking they already knew how to do everything, but the real issue was training those who didn't have experience. An NCO "is leading people who have never done it. He's got to take his knowledge and ensure his men know what to do. It's the same thing as training an officer, first and second lieutenants. They don't know as much as a platoon sergeant, master sergeant or first sergeant. But the NCO's job is not to impress the lieutenant that he knows more. The NCO's job is to pass on the experience and knowledge, because the officer has an adaptability to be better in that position. The NCO should find a way to do it without the officer knowing he's doing it. He should be able to transfer his knowledge and experience to that lieutenant and make the lieutenant think it was his own idea. That [approach] helps you all the way up to general officers. That's the way you get things done," he explained.

Diplomacy is sometimes a necessity. "NCOs don't know it, but they have to use a little bit of diplomacy, too," he said. "Diplomacy is not just for general officers and diplomats. We all have to use a little every now and then."

SPECIALIST 4-9

A specific change for which Connelly can be credited is eliminating the specialist 4-9 ranks. "I'm the daddy of the elimination of the specialist ranks, and a lot of them didn't like it. But, I'm so proud of it," he said. In fact, he's the first SMA to make the cartoons of the Army Times. "It shows me standing there with a Soldier, and I have a chop ax, cutting the specialist rank off."

Around 1955, "in the Army's infinite wisdom, they decided to enhance the subordinate/leader relationship by creating the specialist ranks." In the process of doing so, many NCOs lost their authority. Since the force was top-heavy, those NCOs who did not actually lead or supervise Soldiers became technicians. "But the way it was implemented was boneheaded," Connelly said.

"When it first came out, I had a sergeant who was a gunner on a platoon leader's tank. This sergeant had won the Silver Star in Korea and had two Purple Hearts. He was a great guy, and I'll never forget him. When the regulation was implemented, it went by TOE positions, and the sergeant's position was to become a specialist 5, which meant he could no longer go to the NCO Club. I said, 'By God, this is wrong.' I was a platoon sergeant then and said if I ever get into a position to change that, I will. I spent the next 15 years mad as hell about that."

Connelly said he might as well have called Soldiers in and told them, "Son, I'm going to promote you. It does raise your pay, which is well-deserved, but you don't have enough rank to tell anybody what to do, and you've got too much rank to do it yourself. So take your pay raise, and God bless you." But the technical specialists were in a catch-22: when NCOs weren't around, responsibility would fall to them; when privates were in short supply, they would have to pull those lower duties.

The elimination wasn't completed until two months after Connelly's retirement. "I sat down with [my successor, the seventh Sergeant Major of the Army] Glen Morrell, a U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy classmate of mine, and said, 'If you do anything for me, make sure that gets taken care of.'"

NCO DEVELOPMENT

Another issue close to Connelly's heart is NCO development. "NCOES is the best thing that has happened to the Army," he said. He had never heard the term until the early 1970s. Until then, NCO education was informal and certainly not a requirement. NCOs typically conducted training at the unit level, but nothing was ever officially scheduled on the training calendar. With the creation of the NCOES program, enlisted Soldiers were provided with a glide path for their professional development.

In addition to NCOES, Connelly would later help develop the regulation for the Noncommissioned Officer Development Program, as requested by Meyer. The regulation not only officially established the program, but it also delineated education requirements and strengthened performance standards.

He's proud to have been a part of everything, he said. "Of course, every sergeant major of the Army does something to improve it. None of us can claim to be the daddy of it. It's been a work in progress, and all of us [SMAs] have contributed in some way. Those before us took the hard knocks, never having the opportunity to go to the few schools available but were great heroes and leaders during war and peacetime."

Connelly is the first sergeant major of the Army to have graduated from USASMA. There was a pilot course of about 100 Soldiers before him, but his class, number 2, had the full curriculum that was approved and set. He said attending the course was perhaps one of the best things he ever did, despite his commander offering to get him out of it.

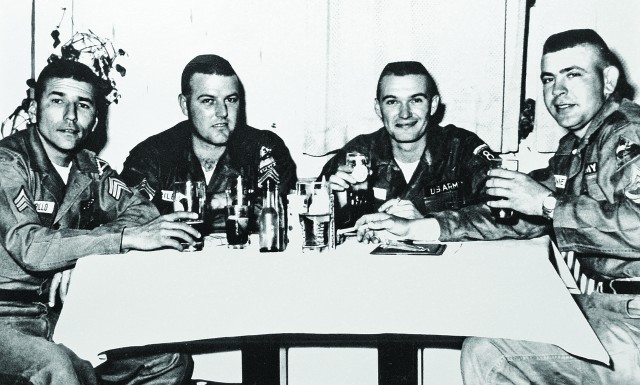

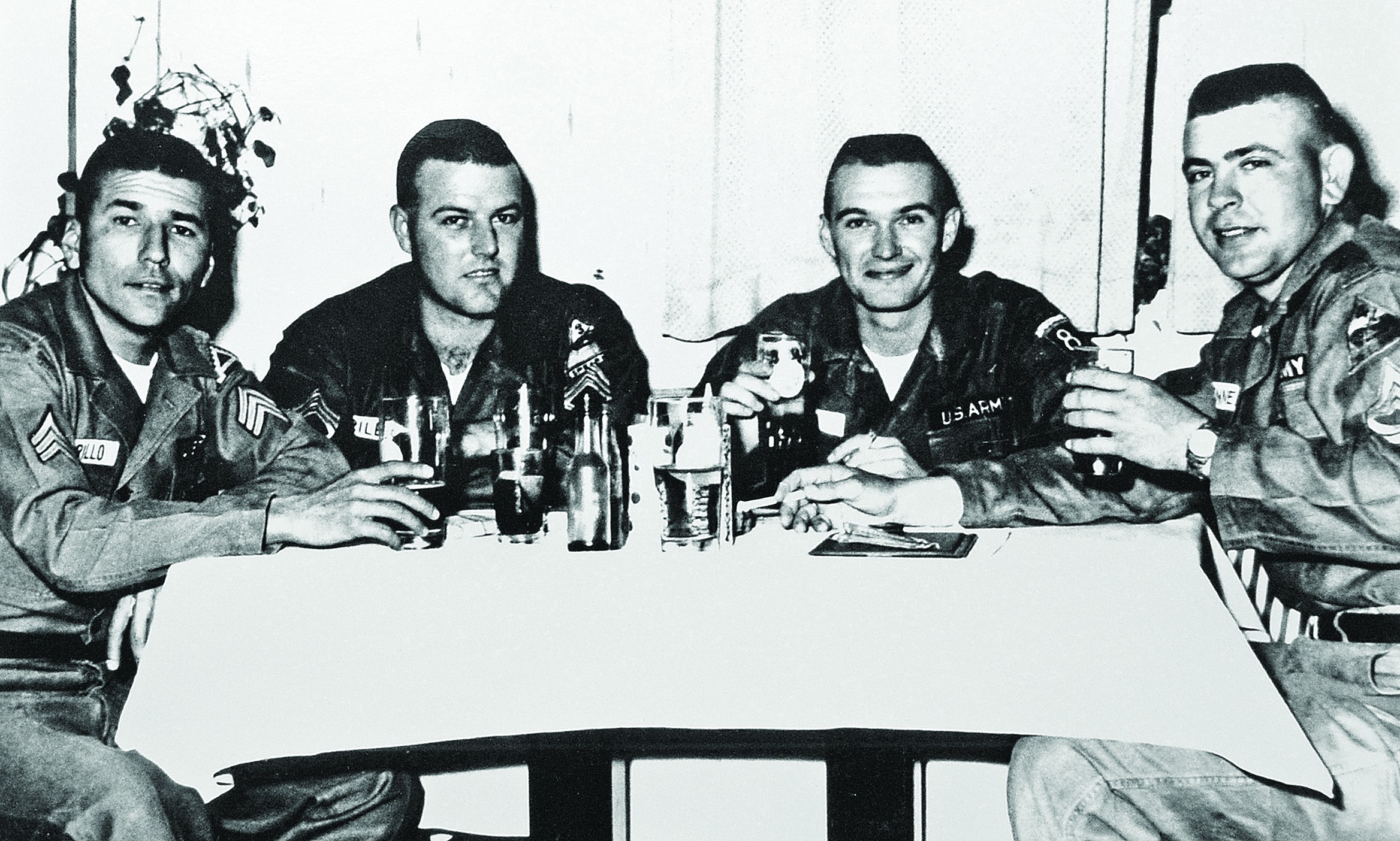

He describes today's NCOs as being much more informed and better educated. "They speak well; they use proper English. They aren't big smokers and drinkers like we used to be," he said.

Connelly said he and his cohorts used to go to the NCO Club and "solve more problems than the Army had. We got a lot done over there. Back then, everybody smoked and drank. Even during conferences, everybody smoked. Those days are past. Now, I go to a conference, and nobody smokes. They have a break, and everybody drinks orange juice. When the conference is over, nobody goes to the club. They go get their wives and play tennis or golf. I like that. That's the Army the public would respect if they knew it as well as I do. I'm very proud of the Army, and I'm proud to have been part of it all."

Connelly says his career has indeed come full circle. He is scheduled to be inducted into the Georgia National Guard Hall of Fame on Aug. 15.

Contact Linda Crippen at linda.crippen@us.army.mil.

Social Sharing