Enabling a sustainment system that provides the combatant commander with the freedom of maneuver to establish and retain the initiative in order to conduct decisive action over long distances is key to winning wars.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's series of initial failures during his march to Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1862 and 1863 brought him to this realization. Gaining freedom of maneuver through a strong sustainment system led him to victory.

SETBACKS AND FAILURES

Grant began his campaign to capture Vicksburg in November 1862 only to confront setbacks and failures. His first attempt was a two-pronged campaign consisting of an advance by both land and river to the region between Vicksburg and Jackson, the Mississippi state capital.

During this attempt, effective cavalry raids by Confederate generals Nathan B. Forrest and Earl Van Dorn effectively disrupted Grant's extended supply lines and destroyed his northern supply depot at Holly Springs, Mississippi, forcing him to cancel the overland element of his campaign. The waterborne element, commanded by Gen. William T. Sherman, met the same failure. After disembarking just north of Vicksburg, Sherman's force was decisively defeated at Chickasaw Bayou.

LESSONS LEARNED

In his memoirs, Grant claimed it was Van Dorn's raid that showed him how the Army could forage and requisition supplies locally instead of depending on a fixed, garrison-based supply line. After the raid on Holly Springs disrupted the supply line, the Union Army had to find another way to resupply. Grant realized that the area of operations could provide food for his troops and pack animals.

Transporting bulky forage over land for pack animals had especially hindered operations because of the tremendous space that it occupied in wagon trains. The amount rose exponentially the farther units operated from fixed logistics bases.

In addition, the need to garrison the intermediate supply bases required the stationing of combat and support forces, which decreased the combat potential of the Union Army as it advanced. Once freed from this requirement, more Soldiers could be brought to bear in combat operations.

Grant planned his future land operations against Vicksburg based on two principles. First, he would use the Mississippi River and its tributaries to move and stage supplies in support of Union land offensives. Second, he would not establish fixed supply garrisons to sustain the advance but instead would disconnect as much as possible from his logistics bases and operate independently.

The Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River and could operate freely. The real question was if Grant could successfully operate without fixed supply lines and with limited lines of communication while on the march and seeking decisive action against the Confederate army.

WATERBORNE LOGISTICS

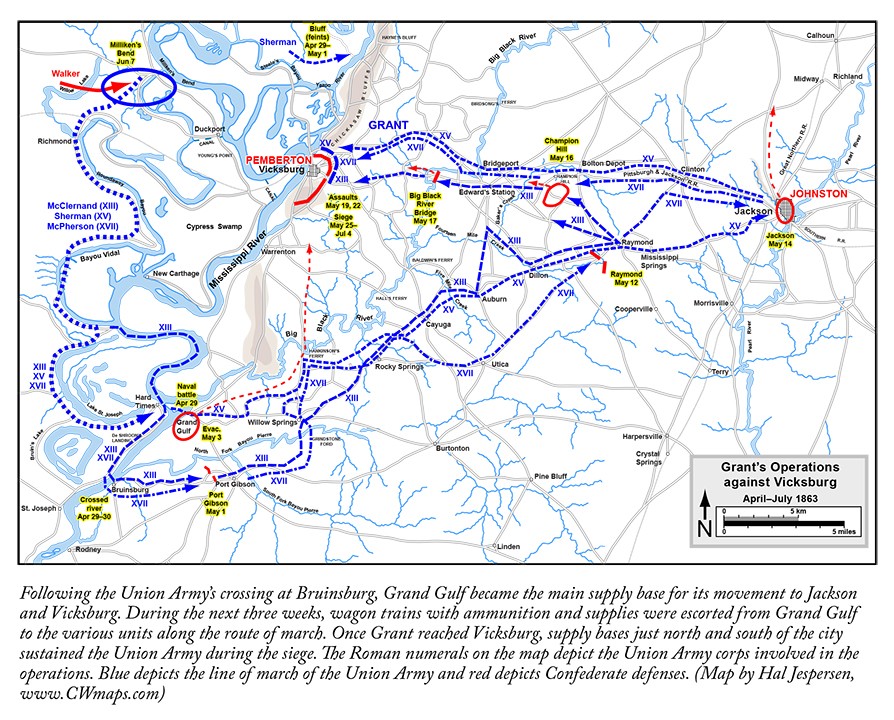

Grant established a series of supply bases on the west side of the Mississippi River in Louisiana. The supply base at Milliken's Bend served as the largest and was located just 20 miles upriver from Vicksburg.

A network of roads and navigable bayous extended nearly 70 miles south along the west side of the river, bypassing the impregnable river fortifications of the Confederate army at Vicksburg, Warrenton, and Grand Gulf. The Union established intermediate bases at Young's Point, New Carthage, Perkins Plantation, and Hard Times. These bases provided logistics support to Grant's three corps as they marched south from Milliken's Bend in April to prepare for an amphibious assault across the Mississippi River south of Vicksburg.

Grant suffered several setbacks in his operations against Vicksburg in early 1863, but the solid foundation of his logistics system gave him the operational freedom to try alternate advances on Vicksburg without losing ground from his primary base at Milliken's Bend.

By the end of March, Grant had ordered Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand and his XIII Corps to depart Milliken's Bend and march south in order to cross to the east side of the Mississippi. On the nights of April 16 and April 22, ironclad gunboats and transports steamed south, under the command of Rear Adm. David Porter, and ran the gauntlet of Vicksburg defenses. Grant used Porter's gunboats and transport ships south of Vicksburg to transport the Union Army across the Mississippi.

The Union Army landed at Bruinsburg on April 30. By the end of the day, 22,000 Union Soldiers had disembarked. During the next week, Grant brought all three corps of the Union's Army of the Tennessee to the east side of the river at Grand Gulf and prepared for an advance against Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston at Jackson.

"I was now in the enemy's country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies," Grant wrote in his personal memoirs. "But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships, and exposures, from the month of December previous to this time … were for the accomplishment of this one object."

SUPPLY IN MOTION

Grant's memoirs reveal that following his capture of Grand Gulf on May 3, he decided to "cut loose" from his base of supply and live off the land by foraging in the countryside as he advanced through Mississippi. Many historians and readers of Grant's memoirs interpret this to mean that he completely severed his line of supply to the Mississippi River. In reality, Grant maintained a flexible supply system after learning lessons from his army's defeat at Holly Springs.

During the inland march and subsequent battles at Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and Big Black River, Grant continued to receive critical supplies by wagon train. Brigades escorted these trains from Grand Gulf inland, providing "supply in motion" and eliminating the need to garrison and protect temporary supply depots along the line of march. These supplies consisted of commodities such as ammunition, weapons, medical supplies, coffee, and hardtack that were not available through foraging operations.

On May 14, Brig. Gen. Francis Preston Blair Jr. completed the escort of one wagon train in excess of 200 wagons to the outskirts of Raymond. This resupply proved crucial following the battles of Champion Hill and Big Black River on May 16 and 17.

As a result of the defeat at Holly Springs, Grant was inspired to order his subordinate commanders to complement this supply with foraging operations to provide the bulk of food for the troops and animals. Wagon trains and foraging operations supplied the Union Army with all of the commodities it needed until its encampment outside of Vicksburg.

EXPEDITIONARY LOGISTICS

When Grant finally arrived at Vicksburg on May 18, he had already set in motion the establishment of river supply bases just north and south at landings in Warrenton on the Mississippi River and Snyder's Bluff on the Yazoo River. Porter was able to provide food from the new supply base at Snyder's Bluff to the Union Army encircling Vicksburg as early as May 21.

The risk Grant assumed paid off. Vicksburg was under siege and ample supplies were routinely provided to the Union Army.

Establishing a flexible sustainment system to support his campaign against Vicksburg was Grant's key to success. Initial failures halted and turned back the Union Army, but once Grant began to rely on the Mississippi River as the backbone of his supply system, he could cut loose from a rigid, supply-base system and conduct high-tempo decisive operations deep into Confederate territory.

The Confederate army's inability to react effectively to Grant's movements enabled Grant to win a swift set of battles and lay siege to Vicksburg. Success at Vicksburg opened the Mississippi River to the Gulf Coast and demonstrated to President Abraham Lincoln what could be accomplished by a commander backed by expeditionary logistics.

Grant was ordered east to become general-in-chief of all Union armies. In this position, he exhibited all of the characteristics of sustainment prowess he had learned at Vicksburg. The lessons learned during the Vicksburg Campaign were put to use during Sherman's March to the Sea and the Army of the Potomac's Overland Campaign in 1864.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Karl Rubis is the Ordnance School and Ordnance Corps historian. He holds a bachelor's degree in history from Pepperdine University and a master's degree in American history and military history from the University of Kansas. He is a graduate of the Naval Command and Staff College.

Brig. Gen. Kurt J. Ryan was the 39th Chief of Ordnance. He holds a bachelor's degree from York College, a master's degree from the Florida Institute of Technology, and a master's degree in strategic studies from the Army War College.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

This article was published in the July-August 2016 issue of Army Sustainment magazine.

Related Links:

Discuss This Article in milSuite

Browse July-August 2016 Magazine

Army Sustainment Magazine Archives

Social Sharing