FORT MEADE, Md. (Army News Service, Sept. 12, 2014) -- For one brief, excruciatingly hopeful moment, Evelyn Sloat thought the Army officers at her door were there to tell her that her son, Spc. 4 Donald P. Sloat, was coming home from Vietnam.

Another local boy, one of Sloat's classmates, had been killed and Evelyn thought her son might have been assigned the grim task of escorting Edgar Pulliam Jr.'s body back to Coweta, Oklahoma.

Coweta ultimately lost eight sons in Vietnam, and claims the highest per capita casualty rate in the nation for that war.

And then she looked a little closer: The men at her door were in dress uniforms. They carried themselves stiffly, somberly, as though they dreaded the mission before them. Sloat was coming home all right, but he wouldn't be kissing his mother on the cheek or fishing with his older brother, Bill, or playing with his younger siblings. She would have a funeral to plan, not family dinners. She screamed in anguish.

Evelyn had already lost her 12-year-old son Bruce to a freak accident at a baseball game a few years before, and had just barely recovered from her grief. The moment she realized another son had been killed was "awful," remembered Bill, who was visiting when the notification team arrived. Bill had the somber task of picking up his three younger siblings up from school and breaking the news: Don had been killed in action in Vietnam, Jan. 17, 1970, when he stepped on a landmine.

Only that wasn't what happened.

Sloat had died a hero, the details lost in the confusion of war for almost 40 years, until a cousin stumbled across a tribute to him online. Just a few short weeks later, former Spc. Michael W. Muhlheim summoned up the strength to call Evelyn. He had been meaning to for decades, but that day was so traumatic that he hadn't been able to talk about it. He was finally ready. Sloat, he told the family, had willingly sacrificed himself to save his squad from an enemy grenade. He had even been nominated for the Medal of Honor.

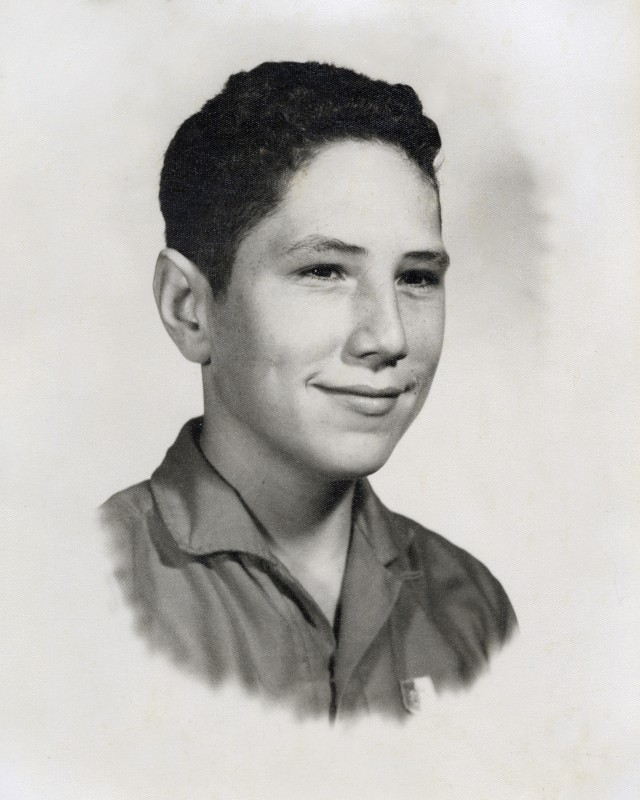

At a time when many young men were leaving the country to avoid the draft, Sloat volunteered. He didn't have to join the Army, and he didn't have to go to Vietnam. But he and a friend agreed to enlist together -- Bill believes Sloat wanted to use the G.I. Bill to finish his college education -- and Sloat had always been extremely stubborn and tenacious. So when a physical revealed that he had high blood pressure and would be ineligible to serve, he kept going back to the doctor and then back to the recruiter until medication finally controlled it enough. He must have tried at least five times, Bill remembered. He finally joined the men of 3rd Platoon, Company D, 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, Americal Division as a gunner, in the fall of 1969.

They were based out of Fire Support Base Hawk Hill, which was located southwest of the coastal city of Danang, but they didn't see it much. The men would spend three weeks at a time out on patrol in what they called the bush, but what could be anything from coastal lowlands to rice paddies to mountains to the jungle, anywhere between the South China Sea to the east and the Laotian border to the west.

Each platoon in the company generally worked on a three-day-and-night rotation, remembered Muhlheim, explaining that one night the platoon would go out on a night ambush. The next day and night they'd stay back in camp and guard the gear, and then the third day they'd go out on a patrol, constantly on the hunt for the enemy and wary of the inevitable booby-traps, which, he said, "were really, really awful. You can handle slugging it out with the enemy," but the booby traps were a special kind of torture."

During those three weeks, he explained, two or three men would usually be killed, and another six or 10 might be wounded badly enough to be sent back to the "world," as Soldiers called the States.

"I think the year I was there we had something like 32 guys killed in the company out of a hundred guys. It was not real common to have a guy make it through the year without getting wounded and sent home," Muhlheim said, noting that he was one of the exceptions. In fact, he said that while the men talked about their hometowns and their girls, they intentionally avoided getting too close, knowing that would only make it harder when a buddy was killed. They'd rag on each other, "joke around a lot about stuff -- you know how guys when they get together are doing things, how they just kind of joked about what they were doing."

At about 6 foot 5, however, Sloat, who had played basketball and football in school, made a big impression: "He was a guy that really went -- whatever we were involved in, he played an essential part. He was a guy who had it together and got things done."

Perhaps reminded of his kid siblings, Sloat was gentle and generous with the local children. He was a good Soldier, a dependable Soldier, a brave Soldier. In fact, when he died, he had already earned a Bronze Star, an Army Commendation Medal and several other medals.

"Well guess what," Sloat wrote to Evelyn in December 1969, "I've been put in for another medal. I guess they think I am really gung-ho or something. They told me I did an outstanding job and they were putting me in for another one. If I keep it up, maybe they'll let me out of the field."

The next month, in his last letter home, Sloat explained that he was being considered for a special rest-and-relaxation trip to Thailand as a reward for his actions.

It was a winter monsoon season and the clouds would "come bubbling over the mountains from the west to the east. It was just raining almost all the time," Muhlheim remembered. The men spent much of the monsoons either trekking through the rain or huddling two by two at night in hooches built from bamboo poles and extra Army ponchos. Digging trenches to direct the water away from their makeshift shelters and exhausted bodies didn't quite work, and the men were cold, wet and dirty all the time. Sometimes they were in the field so long or the weather was so bad that the Soldiers ran out of rations. Still, "the Army expected us to keep operating, and we did."

Sloat complained several times in his letters home about how dirty he was -- once he had to go 20 days without bathing -- or about the jungle rot that set in after even the tiniest cut. So he was looking forward to spending time in Thailand and civilization.

"I'm in pretty fair shape, long and lean," he wrote to Evelyn. (He wrote separate, more graphic letters to Bill, urging him not to enlist.) "They have been working us pretty hard lately. It seems they think we are animals or something. It's bad enough we've got to be out in the field and then having to run patrol 24 hours a day. I guess I probably sound a little harsh. I'm probably going to have to take my R&R before I expected. So that I can get away from this for a little while."

January 17, Sloat's squad was ordered to act as a blocking element for a contingent of tanks and personnel carriers in the Que Son Valley. They'd been taking the same trail down to the valley for several days to check on the area after the unit had killed a Viet Cong guerilla in a bombed-out French village.

"This is not a good idea in Vietnam, to keep going back there," Muhlheim said.

The valley started out wide and then narrowed toward the bottom, and it was there, as the men were unloading their equipment and getting set up, that "all of a sudden the tracks opened up and all of these tracers (from the mechanized unit) went flying over our heads about 12 feet off the ground," Muhlheim remembered. He got on his radio to report the attack and commanders ordered the men back up the trail as fast as possible.

Grabbing their gear so quickly that it hung off of them, the Soldiers scrambled up the trail, bunched together instead of spaced out. And then the squad leader, Sgt. William "Sergeant Bill" Hacker, who was running point, tripped a wire that activated a grenade. Both he and Sloat yelled "booby trap!" but with the noise of the .50 machine guns, no one heard the warning.

Sloat, however, saw the grenade and reached to pick it up. Realizing that he was surrounded by other Soldiers and there was no time to throw it, Sloat doubled his body around the grenade.

The resulting explosion was so strong that Muhlheim was knocked off his feet and temporarily senseless.

"I was laying on the ground trying to figure out what happened, and I couldn't hear anything," he recalled. "After a few seconds the thought hit me that we must have hit a booby trap, and then I thought, 'Wow, we hit a booby trap and nobody got wounded' because I couldn't hear the moaning and groaning of the guys that were wounded. Then my hearing popped back. I started up the trail there. I stopped at each guy and kind of talked to them and tried to reassure them that they were going to be alright and everything and then I got to Don and he had been killed." It was a horrible sight, one that he has spent the rest of his life trying to forget.

That's just the kind of guy Sloat was, said Muhlheim, who wouldn't find out exactly what had happened for several months after Sloat's death. "You know," he mused, "when something like that's happening, you don't really have time to think. You just respond. I think Don was the type of guy who was just geared to respond."

That single explosion wiped out half of the squad, which was already operating at two-thirds strength, with Sloat killed, and Hacker, Elwood Tipton and DeWayne C. Lewis Jr. seriously injured.

"It is my firm belief that I would not be alive today (except) for the heroic act that Don did that day," Lewis later swore. "I was only five to eight feet behind Don when the grenade went off. This act saved my life."

Evelyn, her daughter Karen McKaslin and Bill agreed, had had a very difficult time coming coping with the death of second child, but that news that Sloat had died a hero rejuvenated her, and she made it her mission to ensure that her son received the recognition he deserved. Evelyn didn't live to see it, although her children credit the quest with keeping her alive for quite some time, but Sloat will finally receive the Medal of Honor in a White House ceremony, Sept. 15. They only wish their mother could be the one to accept the award.

"It just showed his character. It was who he was and how he was raised. This was her son and she was extremely proud of all of her children, but because of his action, she wanted that recognition for him. He had sacrificed and she wanted the recognition for him. She knew this day would happen," said Karen, who is looking forward to visiting the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., and doing a rubbing of her brother's name on the wall.

"This was extremely emotional," said Bill. "It's Don's award, but we feel like it's Mom's story. "It's a true honor, but people are people. Whether he was the Medal of Honor [recipient] or not, he was my brother, and I would much rather have my brother than what's happening for him now."

"I was really happy," Muhlheim said of the news, "very happy. I was amazed. After all of that time I thought that it could never happen, you know. I feel like this medal represents the stories that will never be told."

Related Links:

Two Vietnam War Soldiers, one from Civil War to receive Medal of Honor

Medal of Honor: Spc. 4 Donald P. Sloat

STAND-TO!: Medal of Honor for Command Sgt. Maj. Bennie G. Adkins and Spc. 4 Donald P. Sloat

Social Sharing