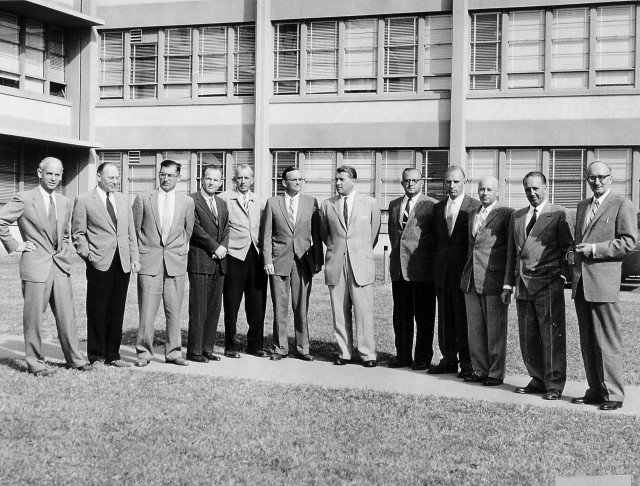

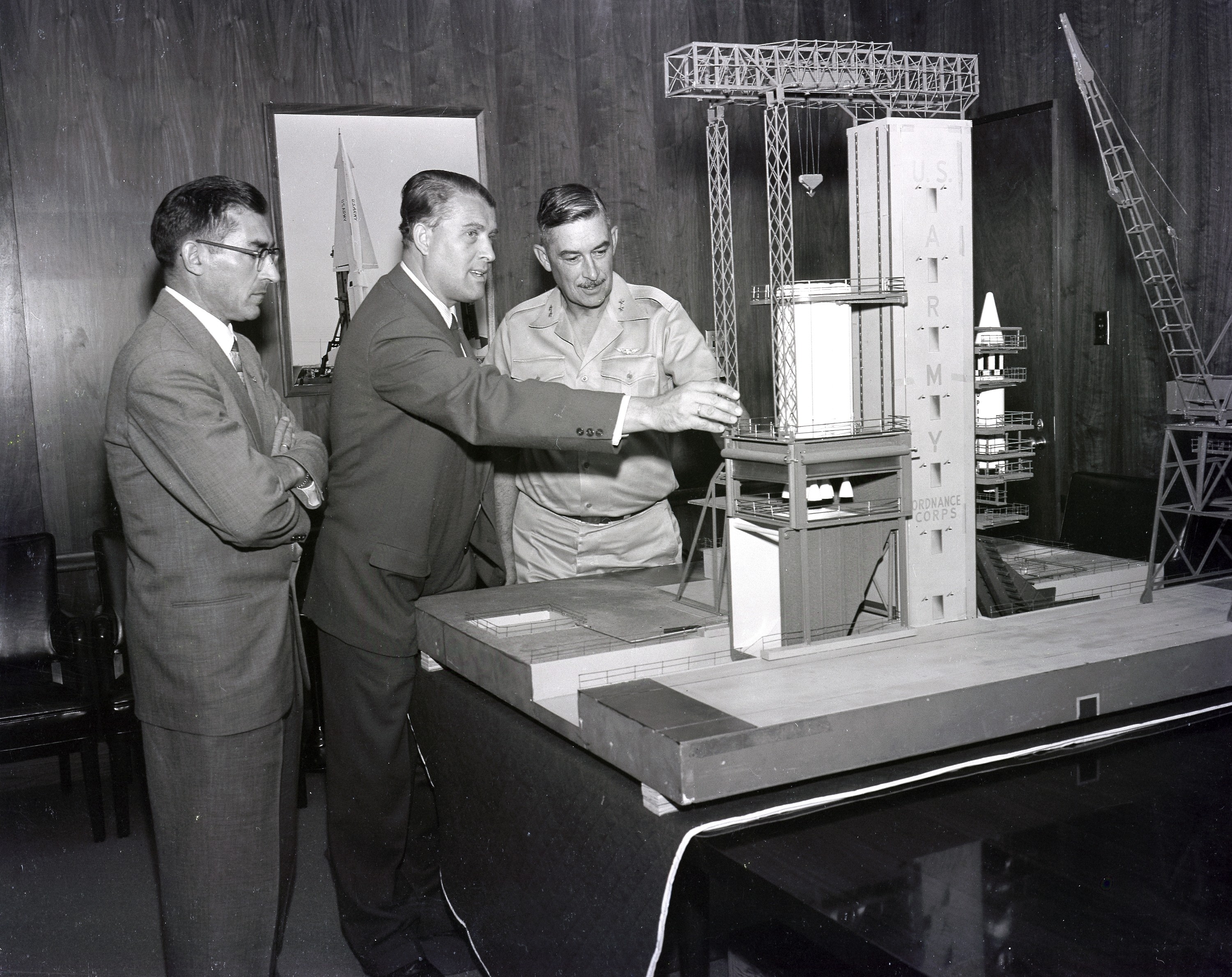

Rocket Pioneers Wernher von Braun, Bernhard Tessmann and Karl Heimburg built early U.S. military rockets at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Ala., home of the U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command and the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command in April 1950.

Their stories, first reported in Soldiers magazine in 1989, recap the beginning of the U.S. Army\'s rocket program, born of war and today preventing war, and they trace one man's dream of space exploration from World War II Germany to America's continuing space program.

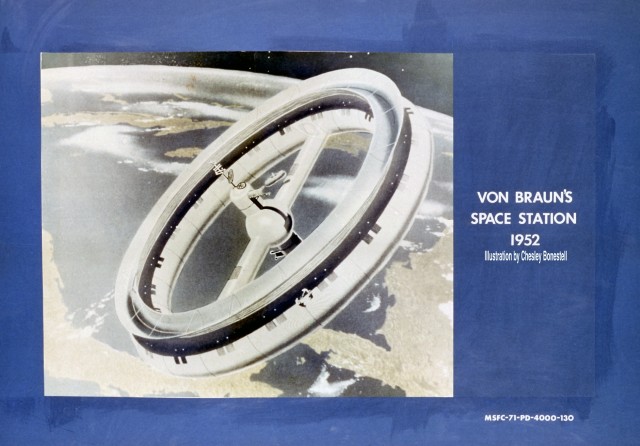

Legend has it that in 1924, when he was 12, Wernher von Braun strapped skyrockets to his wagon, ignited them and watched the charged toy soar down a busy Berlin street. While his friends spent summer days admiring the newest Daimlers and Mercedes touring his fashionable neighborhood, von Braun gazed at the clouds and dreamed of possibilities far beyond.

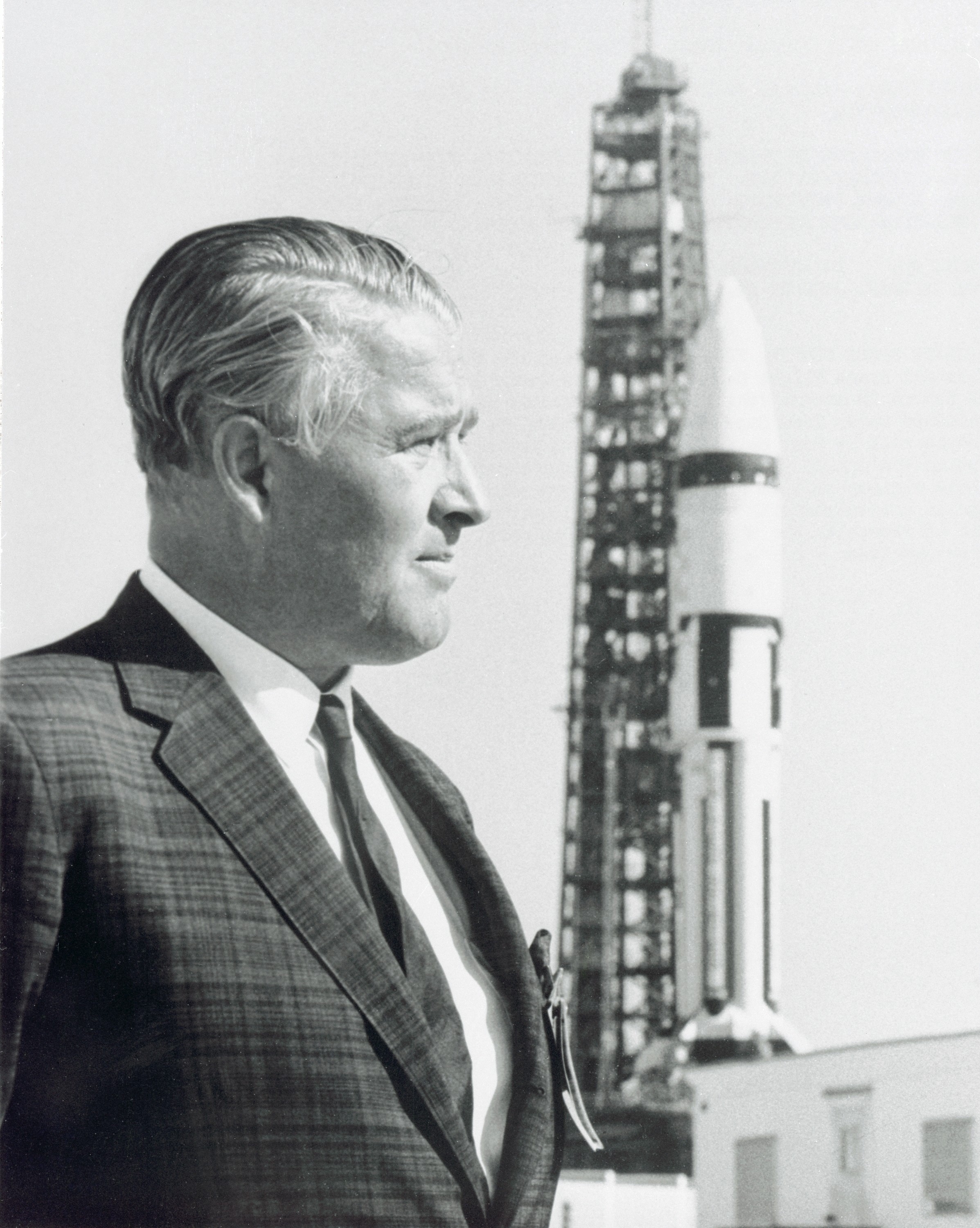

It would be another 45 long, though fruitful years before he would help land the first man on the moon in July 1969 via his Saturn V rocket. When astronaut Neil A. Armstrong stepped on the lunar surface, von Braun realized part of his own dream of man in space.

The story began long before America's Apollo program or the National Aeronautics and Space Administration were born, and long before everyday citizens started to believe that the fantasies that Jules Verne and H.G. Wells wrote about would come true.

Von Braun conducted his earliest official research in Germany in the late 1930s at Kummersdorf, a proving ground about 45 miles from Berlin. He first built small rockets to learn more about guidance systems, said Bernhard Tessmann, a rocket engineer who was responsible for test facilities. Tessmann worked at a Berlin locomotive company when he met von Braun through a colleague in 1936.

"He invited a group of us to dinner at his house one night, but he never got around to cooking it," Tessmann said. "He kept drawing calculations on his blackboard for a rocket to the moon."

"We always had space on our minds," said Karl Heimburg, who began working for von Braun as a mechanical engineer while serving as a private in the German army from 1942 to 1943. "If we talked about space, though, people thought we were crazy. It was too fantastic an idea."

While the men may have talked space, their mission was a military one. Capt. Walter Dornberger convinced Adolf Hitler in the '30s that von Braun's rockets might be a way to circumvent the Versailles Treaty. The treaty ended World War I and prohibited Germany from developing artillery that could fire beyond 15 kilometers - it said nothing about missiles.

To test the missiles, von Braun needed a location where the rockets could be launched out to sea, Tessmann said. His mother suggested Peenemuende, a small island on the Baltic coast, where his father often hunted and fished. The team began work on missiles, dubbed the "A" series. The first real engine test for the team's A-4 long-range bombardment missile was on May 7, 1938.

After years of refinement, the A-4 became better known as Hitler's Vengeance Weapon 2, or V-2. The first was aimed at Paris in September 1944, and for the next seven months, the Germans would rain another 4,000 on France, England and Belgium.

"In 1944, Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler tried to recruit von Braun into the SS," Heimburg said. "Von Braun told him: 'If you fertilize and water a plant too much, you'll suffocate it.'"

Von Braun was hauled off to jail but released two weeks later after the intervention of Dornberger, by then a general.

In prewar America, a West Point ordnance officer, Maj. Leslie A. Skinner, was responsible for the Army's rocket program. The Army had assigned him to its new rocket research group of the National Defense Research Committee in Washington, D.C., in 1940. Money for projects never filtered down, however, nor did guidance as to what he was supposed to develop, according to records of the then Army Missile Command.

Skinner benefited from the work of Robert H. Goddard, who had originated the idea of firing rockets powered by liquid fuel for greater propulsion. Unlike Goddard, who had demonstrated a rocket gun at the end of World War I, Skinner and Capt. Edward G. Uhl unveiled their invention at a more opportune time.

In a private workshop, on their own time, the pair created the bazooka, the first workable U.S. military-produced rocket, according to Dave Harris, a spokesman for the then Army Missile Command from 1962 to 1995.

Within months of U.S. involvement in World War II, the Army adopted, produced and fielded the 2.36-inch-diameter, shoulder-fired anti-tank rocket and tube launcher. The first troops to receive it called it "the Buck Rogers gun."

Skinner's success was short-lived. "A general feeling remained that rockets were inaccurate," said Jacob Rabinow, who designed arming systems at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington, D.C. "Officials joked that they couldn't hit the broad side of a barn."

Nevertheless, rocket research continued at the bureau and at industrial firms and technical institutions around the country.

Back in Germany, three months after the first successful V-2 launch at Peenemuende in September 1944, the British bombed the site, Tessmann said. "After the raids, we were transferred all over Germany." Some 400 engineers and scientists were moved to Lehesten, in central Germany. The site contained a test stand, 800 underground combustion chambers and 16 liquid oxygen production plants.

"One night my wife got an urgent call from von Braun. He wanted to see me," Tessmann said. "Dornberger was at von Braun's apartment when I arrived, and they were discussing what to do with all the documents we had left in the basement of an old school building in Bleicherode, in the Harz Mountains. It was April 1945, and we had just learned that Hitler had committed suicide."

As the Russians advanced, Tessmann and team member Dieter Huzel dodged bullets from the air while leading German soldiers and trucks on a two-day journey to retrieve some 40 tons of rocket sketches, documents and models. Special passes issued by the SS had allowed them to travel freely - until the SS got wind that the von Braun party was moving west, both to surrender and to avoid the Russians.

"As soon as they learned what we were up to, they had orders to kill us," Tessmann said. The two managed to put everything into a mine in Doernten and blast the opening, sealing their rocket research from enemy hands.

"We were lucky to get out of there alive. Later, when we were gathered with the American Army in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, von Braun asked us, 'Just in case we have to go to one country or another, would you be willing to go to America with me''" Tessmann said. The alternatives were Russia and Great Britain.

"For most of us, the prospect of doing research in America was exciting," Heimburg said. "Most of us had lost everything - our homes, families. All we had ever wanted to do was build rockets to the moon.

"Von Braun had always been the inspiration. He'd say, 'If you want to dance, you need music. If you want to do big things, you need money.'" Heimburg said.

"The superpowers evolved from the dissemination of the German expertise between 1945 and 1947," Rabinow once said. "A U.S. Army officer saw that America would be one of those powers."

Col. Holger N. Toftoy (later major general) spearheaded "Operation Paperclip," the Army's code name for identifying those who would be allowed into the United States. Paperclips were attached to the background files of prospective recruits, after careful scrutiny that they hadn't participated in any war crimes or SS activities.

Toftoy had gone to Germany as chief of ordnance technical intelligence after the invasion of Normandy. He examined and reported on captured German rocket facilities, according to Harris.

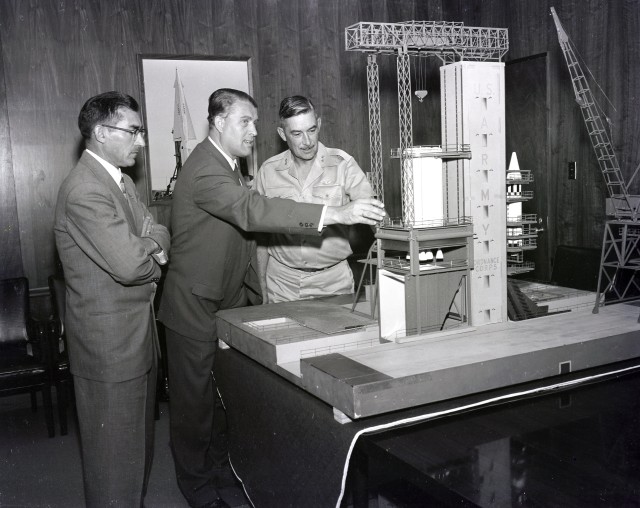

After meeting the von Braun team, Toftoy suggested to U.S. officials that 300 to 400 of the German engineers and scientists be recruited to develop a U.S. rocket program.

The State, War and Navy departments collaborated, but hesitated. Political issues lengthened the red tape. When approval finally came in 1945, the number of recruits was limited to 100. Toftoy, at the time chief of the U.S. rocket group, disregarded the limit and arranged to bring over 118 engineers and scientists.

"A ship sailed in November 1945 with about 100 friends and GIs going home," Tessmann said. "When we arrived at Fort Strong, in Boston, intelligence officers asked us all sorts of questions and required us to take lie detector tests."

From there he traveled to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md., to help sort the rocket documents, since recovered from the mine. Later, the Army sent him to Fort Bliss, Texas, as a facility expert. Most of the others in the group were sent to Fort Bliss or nearby White Sands Missile Range, N.M., then a proving ground; Heimburg emigrated a year later.

During their first five years in America, the team's talents lay pretty much dormant, Heimburg said. They did little more than assemble and demonstrate the V-2s for U.S. officials and members of the Ordnance Corps' 930th Technical Support Group with whom they were assigned.

The big break came in 1949, when the Army centralized its rocket and missile program and moved the von Braun team and the 930th to Huntsville, Ala., to develop ballistic missiles and space-launch vehicles, Harris said.

The announcement was a shock; at the height of the war, more than 19,000 employees had worked at Redstone Ordnance Plant, loading boxcars full of munitions. After the war, the arsenal was on the government auction block and had only 200 employees remaining. Huntsville, population 12,000, had become a sleepy county seat, where watercress was king and cotton fields dotted the red-clay landscape.

"Suddenly the local people were confronted by scientists who talked about research and development," Harris said. "They said 'R and D' meant 'rest and dream,' because they noticed the von Braun team spent lots of time looking into space and writing on blackboards.

"1950 was a time of great urgency," he said. North Korea invaded South Korea, feeding America's fear of yet another U.S. military involvement. The arsenal bustled again with the advent of ballistic missiles.

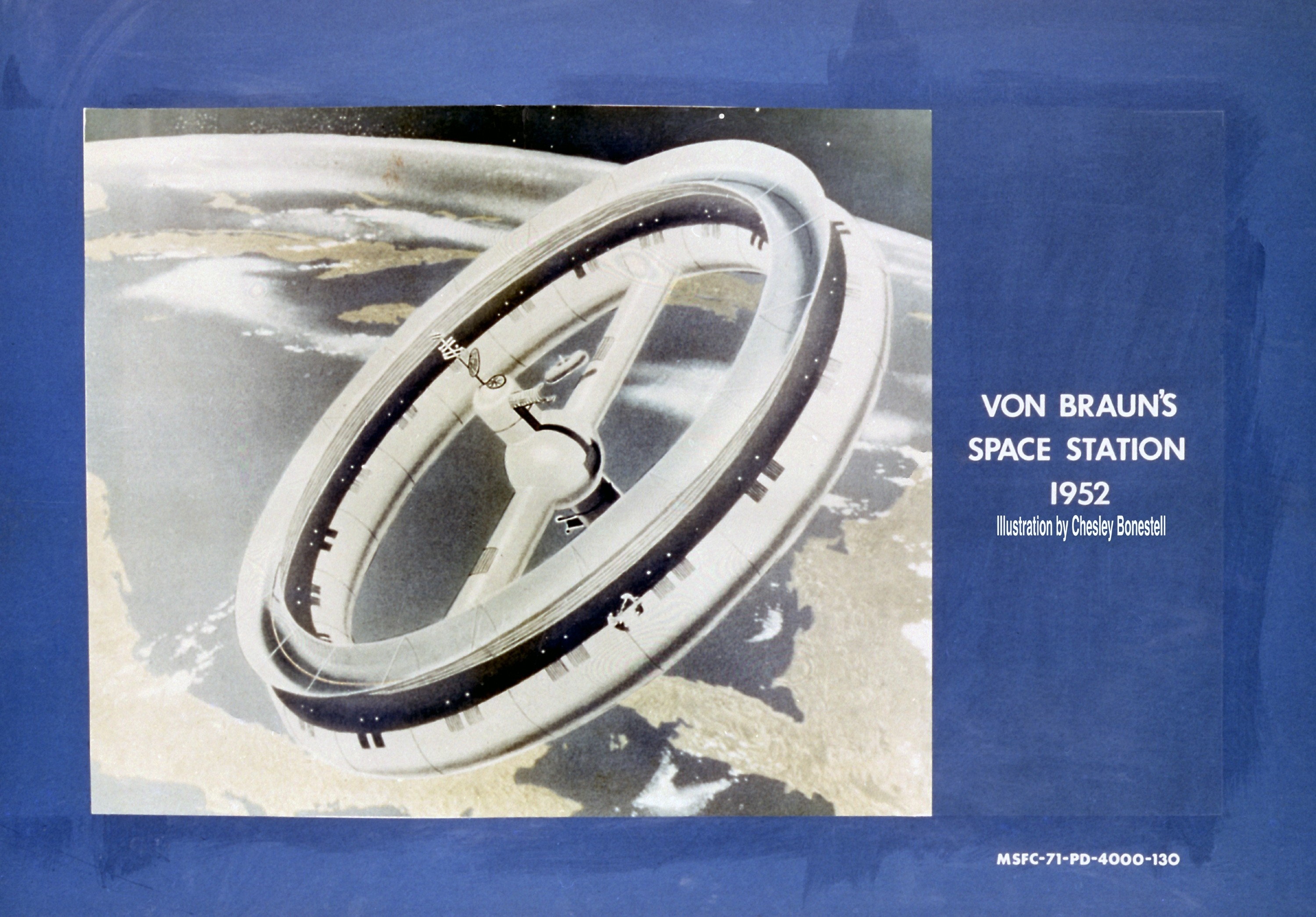

The von Braun team built early U.S. military rockets at Huntsville Arsenal, now named Redstone Arsenal and the home of the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command/Army Forces Strategic Command. One such rocket was the Redstone, the first large ballistic guided missile that could carry a nuclear warhead 200 miles. After the Redstone came Jupiter, a ballistic missile with a 1,500-mile range.

"In October 1957, the Russians put up Sputnik I, the first satellite," Harris said. The Army launched the West's first satellite, Explorer I, in January 1958 via a modified Redstone called the Jupiter-C.

The space race had begun.

The most exciting work for the von Braun team was the eight-year Saturn program, Heimburg said. He was responsible for test stands that could survive millions of pounds of thrust during simulated pre-flights. Von Braun was in charge of the overall effort.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower established NASA in 1958 and two years later transferred 4,000 employees, including most of the von Braun team, and $100 million of equipment from the arsenal to NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, also in Huntsville. Von Braun became the center's first director and continued work on the Saturn program.

In the glory days, Saturn rockets would carry satellites and Apollo astronauts into space between 1961 and 1972, and transport Skylab into orbit in 1973.

Today's jet airplanes and missiles, and tomorrow's space ships that may shuttle people to the moon or other planets, are all outgrowths of the research and development conducted by the von Braun team and other pioneers, such as Goddard and Skinner.

The fledgling military rockets gave way to a continuing U.S. quest to explore space and use space assets for the good of mankind.

Von Braun died in 1977 at 65, while serving as vice president of Fairchild Industries in Germantown, Md. Presidents said he had changed the world in his 20 years in Huntsville and later as NASA's chief planner in Washington, D.C.

Tessmann retired following numerous positions in industry and service with the Atomic Energy Commission. He died in 1998. Heimburg moved with the German rocket team to NASA in 1960 and retired in 1973. He died in 1997.

Toftoy commanded Redstone Arsenal from 1954 to 1958 and then Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md., until he retired in 1960. He died in 1967.

Dave Harris died in December 2002.

Social Sharing