Fort Campbell is leading the way across the Army in COVID-19 vaccinations, but immunization is more important than ever to prevent the recently discovered Delta variant from undoing that effort.

The variant was first discovered in India and has become COVID-19’s dominant strain in the U.S., making up more than 82.2% of new cases and posing a particularly high infection risk to anyone not fully vaccinated.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said approximately 99.5% of deaths from the virus over “the last few months” occurred in unvaccinated individuals.

Existing COVID-19 vaccines remain effective against the Delta variant, but it can spread rapidly through communities with low vaccination rates.

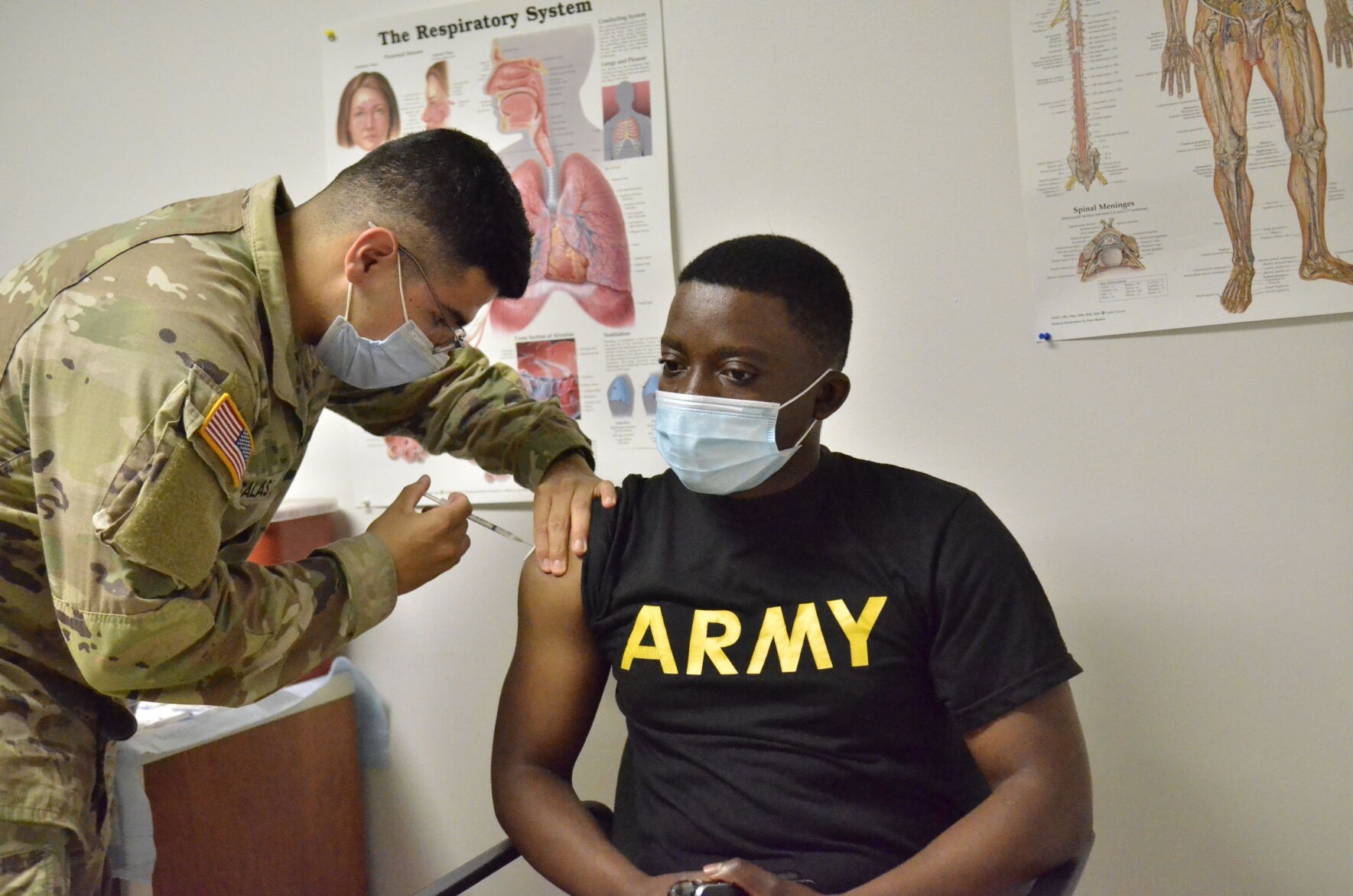

Blanchfield Army Community Hospital considers vaccinations the most effective way to prevent that outcome, and Fort Campbell has reimplemented a mask mandate to further limit spread.

“The CDC put out some new guidance recently,” said Dr. Michael Helwig, a Family medicine specialist at Blanchfield Army Community Hospital who spent 16 months running the installation’s COVID-19 clinic. “Because of the huge, greater infectivity of the Delta variant, they’ve started looking at the data and they’re recommending that if you’re in an area of high or moderate transmission that you may want to consider putting a mask back on.”

In accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation, and Department of Defense and Department of the Army force protection guidance, the installation currently requires face masks indoors regardless of vaccination status, and outdoors for individuals who are not fully vaccinated.

Exceptions to the mask policy include fully vaccinated individuals outdoors, personnel conducting physical training and Soldiers and Families in the immediate vicinity of their on-post residence.

Ultimately, the goal is to prevent the Delta variant from causing an outbreak or mutating into a more dangerous form.

What is the Delta variant?

“The Delta variant differs from previous strains because it is much, much more infectious,” Helwig said. “There are about seven mutations on the spike protein, which you can think of as the key that unlocks the door to the cell. It’s the most important part of making a virus infectious, and those mutations make it very difficult for our immune system to attack it because it doesn’t look like the things we’re already immune to.”

When combined with another mutation that makes the virus reproduce more quickly, Helwig said the Delta variant could potentially place a heavy burden on local hospitals.

There isn’t enough data to suggest the symptoms of the Delta variant are different or more severe than previous strains, Helwig said.

“There are some things we’re seeing that are concerning, though,” he said. “For instance, if you look at the hospitals in Missouri and Arkansas that are filling up, they’re filling up with a lot of people that are in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s. That’s not the population we’re used to seeing.”

Helwig said that’s likely because elderly and high-risk individuals make up most of the vaccinated population in those communities. If the Delta variant continues spreading through younger populations, it could evolve to better target their immune systems.

Protective measures

“The best way you can protect yourself from the Delta variant is to get vaccinated,” he said. “It’s actually as close to a miracle drug as you can get.”

COVID-19 vaccines also are approximately 88% effective at preventing symptomatic infection from the Delta variant, according to a report from Public Health England released in June.

“People will say 88% is really not that good, but the data suggests it’s much better than you would think,” Helwig said. “That’s 88% protection against getting infected at all, but the vast majority of the people that do get infected have either no symptoms at all, or they’ll have symptoms like a mild cold or seasonal allergies. A little bit of runny nose, a little bit of sore throat that lasts a few days and it’s gone.”

Flu-like symptoms also can develop after receiving the vaccine, but Helwig said they usually last around a day — and many patients never experience side effects.

When rarer, more serious side effects – such as blood clots and myocarditis – have been reported, Helwig said the Food and Drug Administration has carefully reviewed the data and taken steps to address them.

“The government is doing its due diligence to make sure they’re able to analyze that data, that there’s not stuff hidden in there,” he said. “They’re trying to make sure we don’t miss something that’s going to hurt somebody out there because we don’t know.”

Helwig said it is important to remember that approximately 2.3 billion people worldwide have received COVID-19 vaccinations, and none of the reported side effects are permanent conditions.

“That compares to COVID-19, where you can be sick for weeks,” he said. “Or if you get long term COVID-19, you can be sick for six months. Some data shows there may be some permanent neurological or cardiological disabilities from it.”

Communicating that message is key in overcoming vaccine hesitancy.

“It’s like you’re in a river or a flood and a boat comes by and throws you the life preserver, but you say, ‘no, I don’t want the red one, I want the white one,’” Helwig said. “And you refuse to take it and push it away. You just keep going down the river until you get snagged by a root or go down the rapids ... sooner or later, there’s a chance there might be another time that we can’t throw them the life preserver.”

Hyperlocal outbreaks

Taking preventative steps can help avoid a hyperlocal outbreak of COVID-19, a situation Helwig said is becoming common in communities with low vaccination rates.

“To understand how to think about this, think of a quilt rather than a sheet,” he said. “If we were all vaccinated across the whole U.S., you could just take a sheet and lay it over the map and it’s all the same – it covers everything. Our country right now is more like a quilt-work ... you can have 70% vaccination rates in one county and 20% in the neighboring county.”

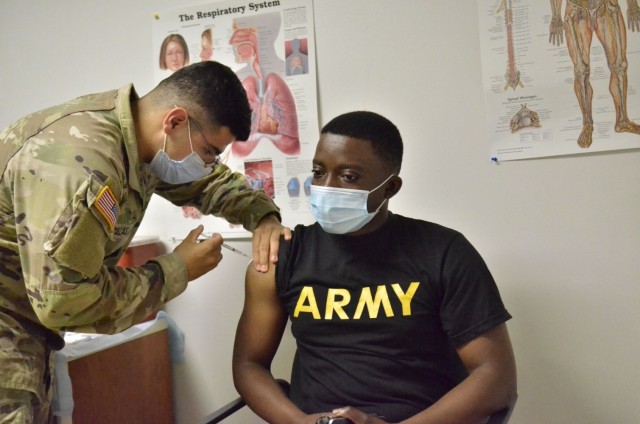

Fort Campbell’s immunization rate is particularly high, with approximately 80% of Soldiers on the installation vaccinated. Helwig said that will likely protect the installation from another heavy wave of infections.

A hyperlocal outbreak in a nearby county is unlikely to overwhelm the installation’s medical system, but that doesn’t mean the community wouldn’t feel an impact.

“The way it could affect Fort Campbell is the way we saw it affect us during our peak back in January,” he said. “If local hospitals fill up, that limits our ability to access them for care that we don’t provide or to access them to be able to transfer patients out.”

BACH’s primary mission is to provide medical care for Soldiers and their Families, who are generally young and healthy. Being resourced for that mission means doctors sometimes need to transfer patients to outside facilities such as Vanderbilt, which is difficult if infections fill hospitals to capacity.

“Middle Tennessee in general was in a very tight position for about a month,” Helwig said, recalling his experience running BACH’s COVID-19 clinic. “What used to take 15 minutes and a phone call to a single hospital ... sometimes it took 12 hours to find a bed.”

Helwig said it’s critically important to increase vaccination rates to stop the virus from mutating further and keep hospitals from being overwhelmed.

“If we ignore the virus, let it keep mutating and just kind of wish it away, we don’t know if the next variant that comes through is going to change that spike protein just enough that it impacts the immune systems of young people,” he said. “My crystal ball’s broken so I can’t tell what the next strain is going to be, but what I hope will happen is people get immunized so there won’t be a next variant coming through and the Greek alphabet will stop at Delta.”

Social Sharing