"Sir, this is our problem statement. Please let me know when you’re done reading it so I can click next slide,” our battalion executive officer said in a bored voice. Then, we watched his face go pale and his eyes widen. What followed was a blistering attack on our professionalism by the commander. I experienced this as a junior staff officer, not once but twice, with different commanders, both times bewildered why anyone could possibly care about a problem statement. However, what the commanders realized, and the staffs failed to understand is that the military decision-making process (MDMP) is primarily an exercise in mitigating risk during military operations, and a unit that fails to mitigate risks is likely to experience operational failure and get Soldiers killed.

Staffs tend to approach each of the subsets in the MDMP as their own things, divorced from all the other subsets, when they should instead be conducting all MDMP as part of the same risk-mitigation strategy. In truth, the problem statement is almost the same as both the initial risk estimate and the course of action (COA) evaluation criteria, all created during the mission analysis step of MDMP, just in different formats. The initial risk estimate is a list of the most important risks to the mission and risks to the force, which will be mitigated during COA development and beyond. The problem statement is the same risks in a narrative format used to focus the staff during mission analysis. The COA evaluation criteria is a list of the same risks again in a different format but refined to focus more narrowly on determining which is the best plan during COA comparison. All three products should be created in tandem by the same people as part of the same process. Critical assumptions help drive the process, and the finished order contains the commander’s intent and a decision support matrix directly derived from these products. By focusing on risk throughout MDMP, the staff can craft a plan to mitigate potential hazards that can kill Soldiers and fail the mission.

Critical Assumptions

To identify risks and create these products, start by identifying your critical assumptions in relation to mission variables. Very often, staffs just list many things that are “likely to be true” that the staff does not know the answer to yet. Think of it this way – the critical assumptions is a curated list of the most important assumptions and is one of your most important MDMP planning products, much like your commander’s critical information requirements (CCIR) is a list of the most important information requirements (IRs) during operations. Critical assumptions, per doctrine, are likely to be true, necessary for continued planning, and things the staff should attempt to turn into facts through requests for information (RFI) or the information collection (IC) plan. I would add one more criterion to this list: the staff should only list assumptions that provide a challenge or an opportunity. Challenges would make the plan much harder, such as an enemy reserve arriving before a hasty defense is prepared. Opportunities are assumptions that, if false, would enable you to have a much greater ability to accomplish the commander’s intent than expected. An example of an opportunity would be exploiting a faster-than-expected seizure of terrain to enable you to continue the attack far into the enemy’s rear. Assumptions that are neither challenges nor opportunities should generally not be listed, since they are unlikely to be useful or necessary for continued planning.

Ideally, representatives of all warfighting functions will create useful critical assumptions in their running estimates and then compile them in a single list. An example is below:

Proposed Problem Statement

Once the critical assumptions are identified, the staff can work on the problem statement. The standard approach is to expand out each of the mission variables into a gigantic run-on sentence, including both important and irrelevant factors. That’s not helpful, and you should instead think how “you’ve done a hundred operations like this before, why are you so worried this time?” What should follow is not a description of “fighting in wooded terrain” that is “defended by a mechanized enemy.” The U.S. Army trains for that fight. How is this mission different, and how do you avoid getting killed?

While ATP 5-0.2-1, Staff Reference Guide Volume 1, states that the “the problem statement is presented as a declarative sentence,” there is nothing wrong with splitting it into two sentences if it improves clarity to your audience. However, I would strongly discourage a long list of bullet points or multiple paragraphs, because “if everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.”

Crafting a useful problem statement requires comparing the current situation to the desired end state to list issues that impede success. It helps to look at the commander’s visualization, guidance, and your commander’s intent. Chances are, your battalion commander already discussed the operation with the brigade commander, and your guidance is focused directly on their visualization of risks. Look also at your mission variables. What about the mission, enemy, terrain, time, troops available, or civil considerations (METT-TC) will make you fail? The goal is not to include all aspects of METT-TC in the problem statement, since the important parts will get buried under extraneous information, but rather to try to look at the problem from every direction. Next, look at your critical assumptions. Are any of them issues that, if not true, would cause your operation to result in failure? And finally, just ask yourself how you would explain the issue informally to a friend or mentor about why the mission is difficult to plan and could fail. In the end, you should have a list of between two and five greatest risks, which, when consolidated, should make your problem statement.

“1-68 Armor must seize OBJ Sapphire with enough momentum to convince the 61st DTG Commander that we are III Corps’ main effort, causing the enemy to commit the DTG Reserve (641 BTG). We must maintain tempo in canalized terrain where the enemy knows we are coming, synchronize our forces to breach a complex obstacle with a limited number of assets, and then establish a hasty defense against a battalion-sized counterattack from the northeast within only thirty minutes after starting the breach and retain enough combat power so that we can establish a deliberate defense oriented northwest against another brigade-sized counterattack within three hours.”

Initial Risk Estimate

The initial risk estimate identifies hazards during mission analysis and mitigates those risks during COA development. Your initial risks to the mission and the force in the problem statement may not match the initial risk estimate exactly, since the products are focused on the staff and the plan, respectively. However, if the risks are not very similar, then the staff clearly created both products in a vacuum, spending extra effort and accomplishing little. To create a good product, examine your critical assumptions, commander’s intent, and use your problem statement. Example:

- Loss of tempo before the breach.

- Failure to breach due to a lack of synchronization or redundancy.

- Not establishing a hasty defense before the 641 BTG counterattack (DTG Reserve) from the northeast.

- Not having enough combat power to establish a deliberate defense against the 644 BTG (OSC Reserve) counterattack from the northwest.

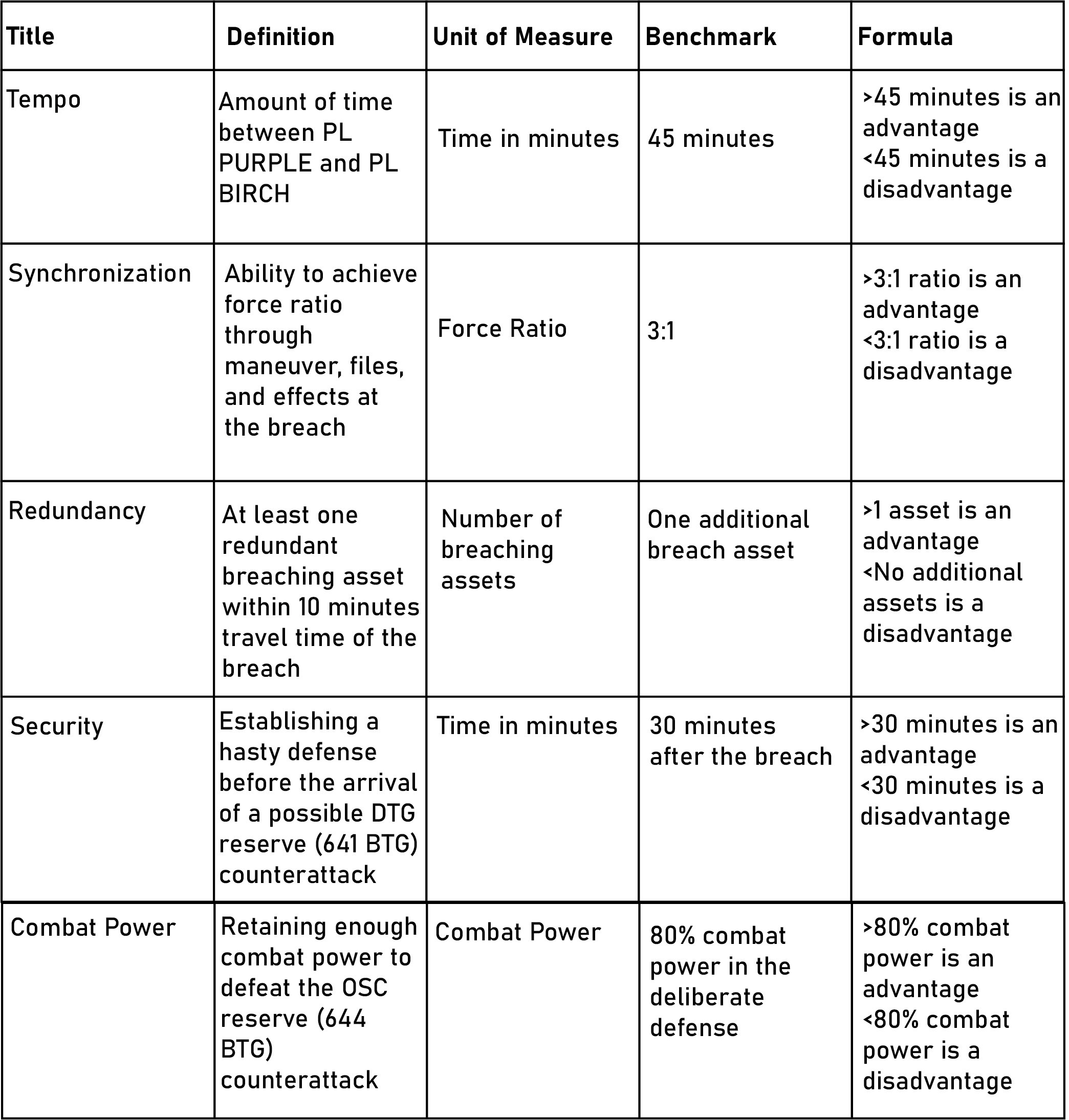

Proposed COA Evaluation Criteria

The COA evaluation criteria are not used until later in MDMP, during the COA comparison step. However, this product is created during the mission analysis step to avoid bias. To create the COA evaluation criteria, look at the principles of war, offense, defense, joint operations, reconnaissance, security, and so on. Also, consider using warfighting functions as topics. Generally, your COA evaluation criteria should mirror your initial risk estimate, though it will need to be refined to be measurable – for example, are you most concerned with the tempo between PL FIR and MAPLE, or, PL PURPLE and BIRCH? Our benchmarks should be defined in terms of risk, such that failure to achieve the specified metric significantly decreases the chance of success. For example, if you expect the enemy reserve to arrive in 30 minutes, your benchmark should probably be 30 minutes for establishing a hasty defense. Of course, too much risk results in a COA failing to be acceptable, feasible, or suitable, forcing staffs to reject it outright. MDMP should generally require between two and five COA evaluation criteria.

Proposed Commander’s Intent

Like the other products, the commander’s intent is created to reduce risk. During the planning process, it focuses the staff on what is important to the commander and should be nested at echelon. During execution, subordinate commanders may have to use it to make rapid decisions when the operation does not unfold as planned. A course of action that does not fit within the commander’s intent is considered unsuitable.

Commander’s intent consists of three parts: the broad purpose, key tasks, and end state. The broad purpose explains why the mission is being conducted. To develop a good broad purpose, look at the mission statements of higher units – how does our purpose nest within theirs? Another way to easily develop the broad purpose is to imagine writing a letter to service members’ families on why they risked their lives in this operation.

Key tasks should generally not be tied to the preferred course of action, such as specific named objectives, routes, etc. If a bridge is destroyed, the enemy is in an unexpected location, or the planned mission is otherwise impossible to do, what should subordinate commanders do instead? As a historical example, consider the airborne operations in conjunction with D-Day. Very few units landed in their desired drop zones, but they did an excellent job of blocking enemy approaches to Utah Beach, capturing causeway exits off the beaches, and establishing crossings over the Douve River at Carentan.

The end state should likewise not be tied to a specific course of action, instead explaining how the enemy is affected and how United States forces are postured in relation to terrain in a more general way. Please note that “minimize collateral damage” is not an acceptable end state, because no one can agree on its meaning. Should United States forces refuse to return fire on enemy forces in urban areas for fear of killing civilians? Can United States forces destroy bridges and roads to prevent an enemy counterattack? Is it acceptable to destroy mosques, power plants, or dams if there is a military necessity? “Minimize collateral damage” is so broad as to be meaningless. A good commander’s intent should be clear, concise to make it easy to memorize, and should ensure shared understanding.

Decision Support Matrix

The other major risk-related product created during MDMP is the decision support matrix (DSM). This is easily created if the staff uses two products. First, prominently post the critical assumptions identified earlier during the mission analysis step of MDMP. Second, the staff should prominently post the “Five Common Command Decisions” as enumerated by then-COL Thomas Feltey and CPT Matthew Mattingly in Armor Magazine, Fall 2017.

- Change of Task Organization.

- Change of Unit Boundary.

- Commit Reserve.

- Transition Phases.

- Execute a Branch Plan or Sequel.

At the end of each “turn” of the wargame, the staff should review each of the assumptions to see if any are currently relevant. Please note that the decision points (DP) will be different at each echelon. Also, a “trigger” is something that happens when certain conditions are met, without the need for additional analysis and is part of the main plan. A decision point, on the other hand, is a deviation from the main plan. Some examples of how these DPs could be identified are shown in the DSM below. Note that the column on the far left (relevant critical assumption) is added to show how a staff uses critical assumptions in the wargame to help derive decision points. It should not be a part of the published DSM. Some of the critical assumptions, when evaluated, will not result in a decision point but will instead prompt the staff to add details to the plan.

Conclusion

An effective staff identifies as many risks as possible during mission analysis by identifying critical assumptions and using the commander’s guidance and higher commander’s intent to create the proposed problem statement, initial risk estimate, and proposed COA evaluation criteria. Those products, plus the approved commander’s intent, are used to create a viable course of action that can mitigate risks. Course of action analysis does more than just synchronize the plan – it is the step where all risks are analyzed in a methodical way to identify decision points and add details to make the plan robust enough to overcome foreseeable risks. No plan survives contact with the enemy, but a plan made with a deliberate focus on risk can be rapidly adapted to achieve the mission with less chance of failure or unnecessary losses.

Major Brett Barton is currently serving as the Team Chief for the Maneuver Captain Career Course - Reserve Component at Fort Benning, GA. His previous assignments include Commander of the U.S. Army Master Gunner School at Fort Benning, GA; Commander of C Troop, 5-1 Cavalry at Fort Wainwright, AK; Executive Officer for the U.S. Army Experimental Force at Fort Benning, GA; and Aide-De-Camp at the U.S. Army Armor School, also at Fort Benning. MAJ Barton’s military education includes the Army Operations Course at Fort Leavenworth, KS; Cavalry Leader Course and Maneuver Captain Career Course at Fort Benning; and the Pathfinder Course at Fort Benning. He holds a bachelor of art in political science from the University of Georgia and an master’s of business administration from Oklahoma State University. His awards and recognitions include the Meritorious Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, Army Commendation Medal with five oak leaf clusters and “V” device, Pathfinder Badge, Parachutist Badge, and Combat Action Badge.

Social Sharing