The Animals in War and Peace Medal of Bravery was instituted in an inaugural ceremony in Washington, DC on November 14, 2019, to honor the work of American animals in war and peace. The medal was created as the American equivalent of the British PDSA Dickin Medal, awarded in the United Kingdom for any animal displaying conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty particularly in the armed forces or civil emergency services. To date, there have been four rounds of inductees for the Animals in War and Peace Medal of Bravery, and nominations for the awards in March 2025 are open until September 30, 2024. Three U.S. Army Signal Corps “Hero Pigeons” have, to date, been honored with the Medal of Bravery.

The U.S. Army’s Signal Corps Pigeon program, which was headquartered at Fort Monmouth, NJ from 1919 until its discontinuation in 1957, remains one of the most requested topics from the CECOM History Office. Gen. Pershing set sail for Europe on May 28, 1917 and arrived in France on 13 June and set up the headquarters for the American Expeditionary Forces in Paris. In July 1917, impressed with the French and British pigeon services, Pershing requested that pigeon specialists be commissioned into the U.S. Army. In November 1917, the Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service received official authorization, and a table of organization for a pigeon company to serve at Army level was published the following June. The company comprised 9 offices and 324 soldiers and provided a pigeon group to each corps and division. By the end of the war the Signal Corps had sent more than 15,000 trained pigeons to the AEF.

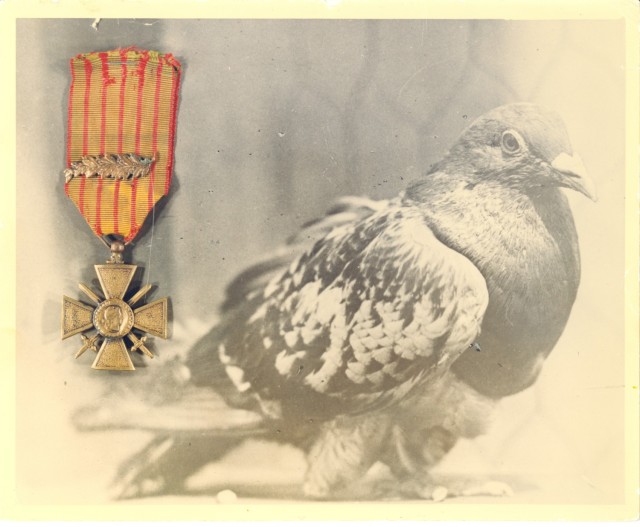

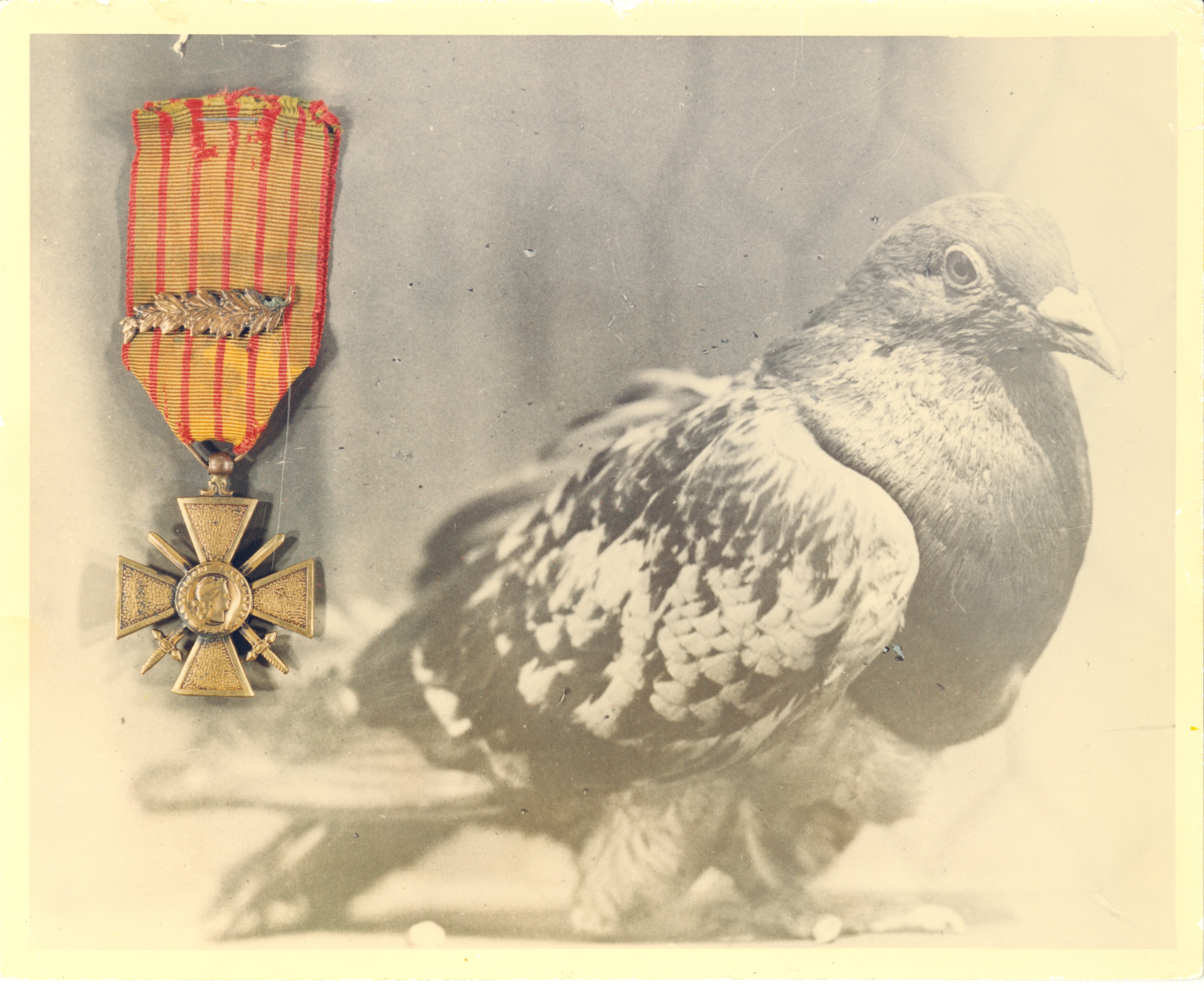

Probably the most famous use of pigeons occurred during the fighting in the Argonne Forest in October 1918 when elements of the 77th Division, commanded by Maj. Charles W. Whittlesey, became separated and trapped behind the German lines. These units became known as the “Lost Battalion.” The Lost Battalion had been pinned down on all sides by the Germans who had surrounded them with barbed wire and machine guns. For five nights they were shelled by both German and American fire – the Americans did not know they were there. Four messengers were sent out and they all disappeared. When runners could no longer get through, Whittlesey employed pigeons to carry messages back to division headquarters requesting supplies and support. Seven pigeons were sent out and they were all shot down. After several days without relief, with hope for survival fading and friendly artillery fire raining down, the men pinned their lives on their last bird, Cher Ami (dear friend), to get word back to silence the guns. Cher Ami had already delivered almost one dozen important messages from the Verdun front to the loft at Rampont. Whittlesey had received a written proposition from the Germans to surrender but he had been instructed not to give up any ground without written instructions. They had one day of rations left, and the men had been reduced to eating leaves and shoots. Fifty percent of the battalion had been killed or wounded. Cher Ami flew 25 miles in 25 minutes, and arrived with his breastbone shattered, and a leg missing, his message hanging by a tendon. Cher Ami completed his mission. The barrage stopped and a detachment from the 77th Infantry Division was soon on its way to rescue the surrounded men. In recognition of this remarkable accomplishment, Cher Ami was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Croix de Guerre and became one of the first widely recognized “Hero Pigeons,” celebrated throughout the country. Gen. Pershing personally saw Cher Ami off on his trip back to America and gave strict instructions that he was to be kept in the captain’s quarters and provided with unlimited rations. He died at Camp Alfred Vail in 1919 and can be found on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

When Cher Ami passed away due to combat wounds in July 1919, the remains were sent to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History for preservation. After being mounted by a taxidermist, Cher Ami went on display at the United States National Museum in the Arts and Industries Building in June 1921. During that timeframe, Cher Ami was referred to as both a hen and a cock. The Smithsonian listed Cher Ami as a male, while the Pigeon Service AEF document listing the returning pigeons designed Cher Ami as a female. While not affecting Cher Ami’s attributed service, the question of the pigeon’s sex has continued to be raised over the past century. Cher Ami was awarded the Medal of Bravery in the inaugural class of 2019. In 2021, the Smithsonian completed DNA analysis of Cher Ami’s remains, finally settling the century-long dispute, with a determination that Cher Ami was male.

There were many other pigeons who earned the title of “Hero Pigeon” in World War I, including Mocker – the last of the WWI hero pigeons to die (June 14, 1937), who was awarded the Medal of Bravery in March 2023. Mocker was a red check pied cock banded AU-17-4084, with breeding unknown. With his eye destroyed by a shell splinter and his head a welter of clotted blood, this pigeon homed in splendid time from the vicinity of Beaumont early in the morning of 12 September 1918, bearing a message of great importance which gave the location of certain enemy heavy batteries. This information enabled the American artillery to silence the enemy’s guns within 20 minutes. Even with the loss of an eye, Mocker continued to fly once he healed, eventually credited with carrying 33 messages during the war.

The success of the homing pigeons in war prompted the Army to perpetuate the service after the Armistice. The Chief Signal Officer established the Signal Corps Pigeon Breeding and Training Section at Camp Alfred Vail, NJ, which would later be renamed as Fort Monmouth. The officer in charge of the British Service supplied 150 pairs of breeders to the U.S. Army. They arrived at Camp Vail, without loss, in October 1919, and resided together with some of the retired hero pigeons of the World War. At Monmouth, the pigeon experts devoted efforts to improving training, breeding, and equipment for the Pigeon Service. A World War I-era joke suggested that the Corps was breeding pigeons with parrots so that messages could be transmitted by speaking!

Pigeon breeding and training had transcended the novelty stage by 1930. New and revolutionary techniques were establishing Fort Monmouth as the most outstanding breeding program in America. By the outset of WWII, the Fort Monmouth pigeoneers had perfected techniques for training two-way pigeons and for flying over water. These efforts paid off during WWII. The Pigeon Center at Fort Monmouth had an emergency breeding capacity of 1000 birds a month. This represented about ¼ of the Army’s anticipated requirement. American pigeon fanciers supplied approximately 40,000 racing pigeons voluntarily to the Signal Corps without compensation. These made up the bulk of the 54,000 birds that the Signal Corps furnished to the Armed Services during WWII. The Signal Corps used its authority under the Affiliated Plan (1940) to recruit civilian specialists into the Army to fulfil specialized requirements, such as pigeon experts.

There were many hero pigeons to emerge from WWII, including G.I. Joe, who was another inaugural recipient of the Medal of Bravery in 2019. G.I. Joe was credited with saving the lives of 1000 allied troops at Covi Vecchia, Italy. The pigeon flew 20 miles in as many minutes carrying an order to cancel the scheduled bombing of the city. The action saved a British brigade which had entered the city ahead of schedule. For this action, G.I. Joe was awarded the Dickin Medal by the Lord Mayor of London in 1946. He was the first - and only - American recipient of this prestigious medal during World War II - a distinction he held for 55 years. After the war, G.I. Joe returned home a hero. He was housed at the Churchill Loft, also known as the U.S. Army’s “Hall of Fame” at Fort Monmouth, along with 24 other hero pigeons. When the Churchill Loft closed in March 1957, G.I. Joe and some of his friends found a new home at the Detroit Zoological Gardens, where he lived out his days until his passing on 3 June 1961. G.I. Joe was stuffed and mounted and is stored at the U.S. Army Museum in Ft. Belvoir, VA. He was brought out of storage and attended the Medal of Bravery ceremony.

Social Sharing