History of Memorial Day

Memorial Day is for remembrance of those who have died in service to our country. The history can be traced back to May, 30, 1868, when Gen. John A. Logan of the Grand Army of the Republic proclaimed a commemoration of fallen Civil War soldiers. Volunteers decorated graves of more than 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers at the cemetery.

General Order No.11 dated May 5, 1868, signed by Logan, proclaimed its purpose:

“… to inaugurate this observance with the hope that it will be kept up from year to year, while a survivor of the war remains to honor the memory of his departed comrades. He earnestly desires the public press to call attention to this order, and lend its friendly aid in bringing it to the notice of comrades in all parts of the country in time for simultaneous compliance therewith.”

Logan’s hope was rewarded, and by the late 1800s, many states declared Memorial Day a legal holiday. After World War I, it became an occasion to honor all those who died in all of America’s wars.

Objects hold memories

Humans have an innate ability and desire to tell stories. Stories passed from person to person, generation to generation help us to remember and preserve the memory of the past. Objects are physical reminders of these stories, which is why many people “collect” things.

Museums purposely collect historical artifacts to preserve history and tell stories through the exhibition of these artifacts. When collected, objects become locations for memory and emotion, both positive and negative.

The Frontier Army Museum at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, collects and preserves 19th century military artifacts to teach soldiers and the public about Army history and heritage. Many pieces in the collection can be attributed to an individual soldier who served, some who perished during battle or while on mission.

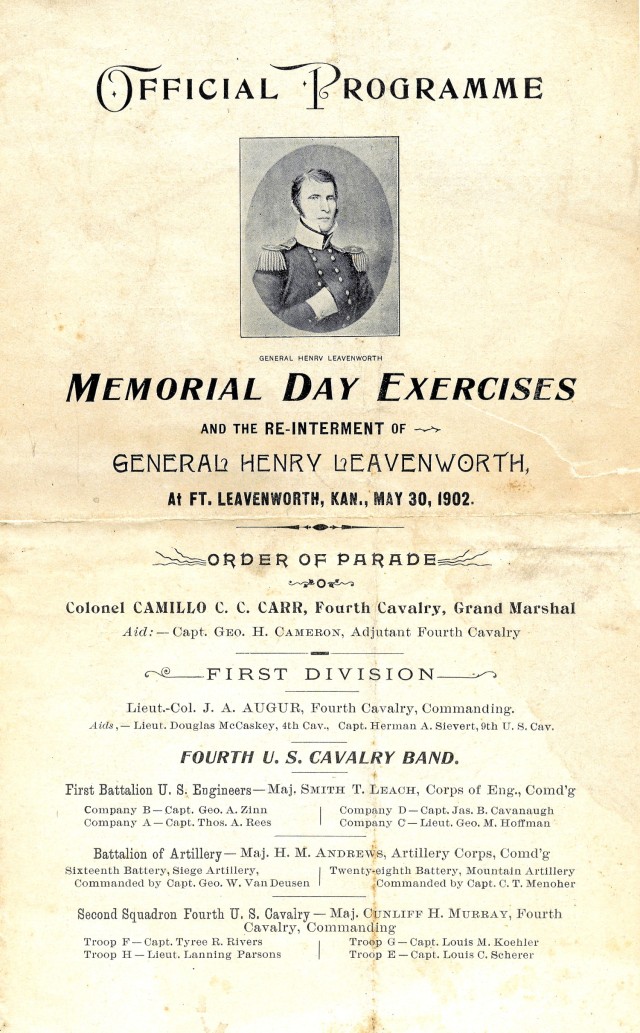

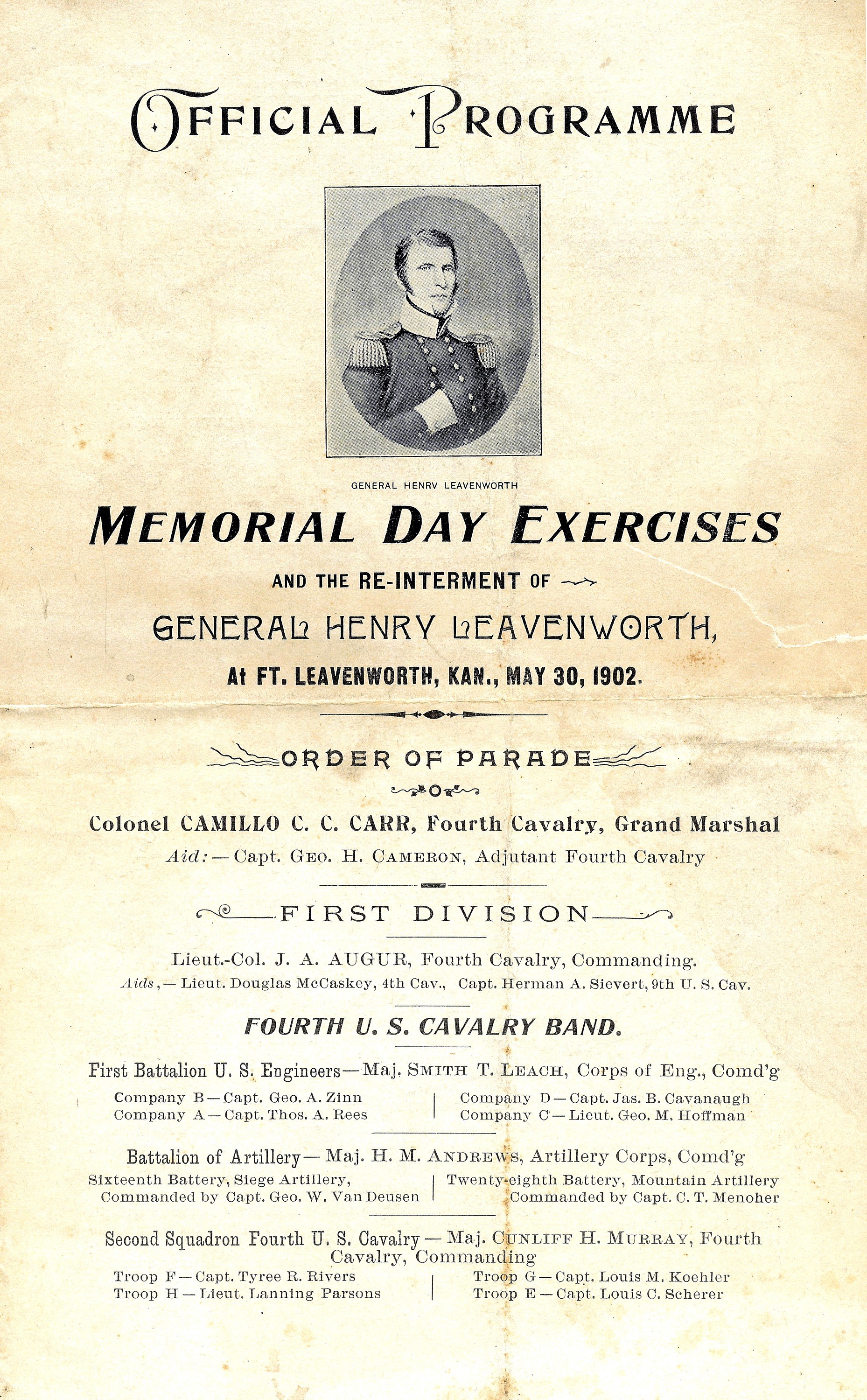

Henry Leavenworth

One such individual who deserves highlight is Henry Leavenworth, the namesake of Fort Leavenworth.

In spring of 1827, Col. Henry Leavenworth founded a cantonment to serve to protect travelers on the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails. Later that cantonment became Fort Leavenworth.

As an Indian agent, Leavenworth traveled throughout the nation creating various posts, including Fort St. Anthony, now Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and working to try and promote peaceful relations among Native American tribes.

While commanding the United States Regiment of Dragoons during an expedition, Leavenworth died from illness on July 21, 1834, near modern Kingston, Oklahoma. While originally buried in Delhi, New York, he was re-interred at Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery in 1902. His final resting place is marked with a large 12-foot-high granite marker adorned with a sculpted eagle atop. The marker is etched with Leavenworth’s achievement of his rank of Brevet Brigadier General, as well as his achievement of establishing Fort Leavenworth.

The cemetery marker is not the only physical object that exists to remind us of Leavenworth’s life and career. Leavenworth’s P1832 general officer’s coat, c1812 foot officer’s sword, and a miniature oil portrait completed just a few months prior to death are housed at the Frontier Army Museum. These items are displayed regularly, and guests can learn about Leavenworth’s contributions to the Army, both in person and through the museum’s virtual online tour at https://frontierarmymuseum.stqry.app/.

These items, both personally owned, and items produced after his death (e.g. tombstone), are physical reminders of this soldier and his impact on Army history.

But what happens when there are no physical reminders that remain? Do we forget the stories or the person?

There are instances when soldiers who served and died for our nation may not have physical objects to carry on their legacy.

No artifacts, no story?

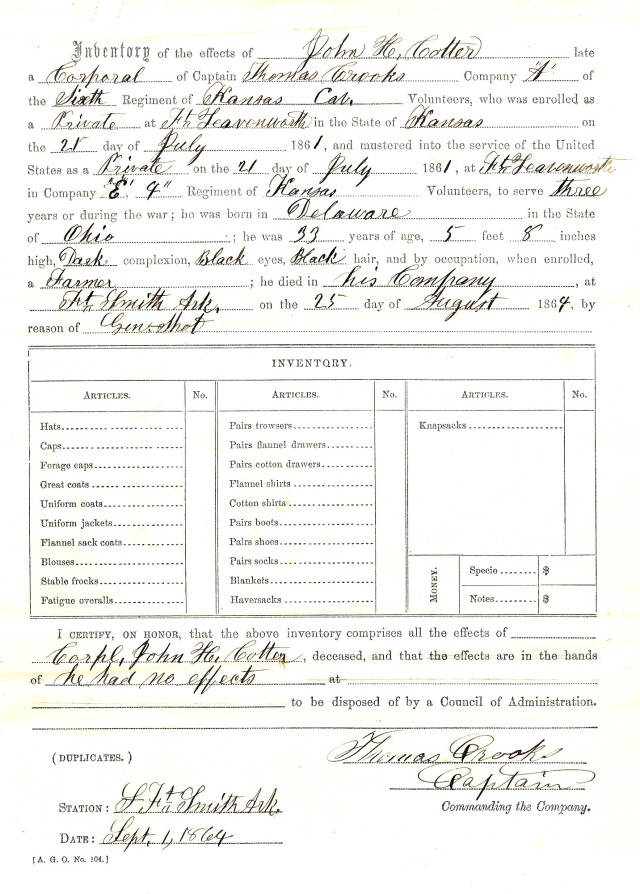

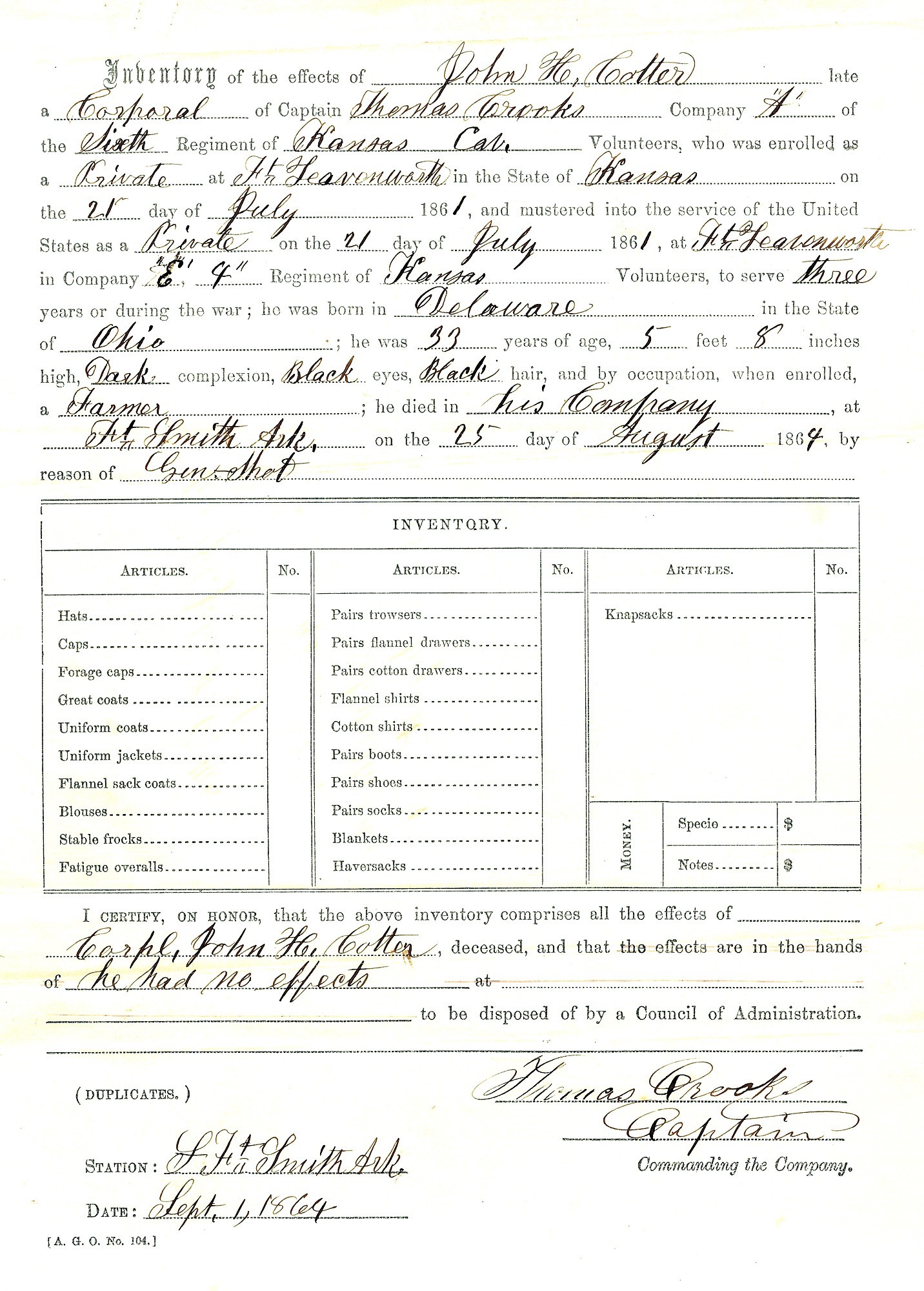

In the museum’s archives is a simple piece of paper that dates to the Civil War.

This paper, yellowed with age, is an Army Regulation form. The form dictates that when a non-commissioned officer or solider dies or is killed in the service of the United States, the Army will take account of their possessions. The form in the museum collection indicates that on Aug. 25, 1864, Cpl. John H. Cotter, Company A, Sixth Regiment of Kansas Cavalry Volunteers, died at Fort Smith, Arkansas, due to a gunshot wound by guerrillas. The form signed by Capt. Thomas Crooks states that “he had no effects”.

Basic documents, such as this, can give us a brief glimpse into the life a soldier.

John H. Cotter

After some research, more information about this individual came to light. Cotter enlisted at Fort Leavenworth in July of 1861. He originally served with Company E of Fourth Regiment of Kansas Volunteers. He died at age 33, placing his birth around 1831. The form described him as dark complexion, with black eyes and hair. Born in Ohio, he worked as a farmer before enlisting.

Around Jan. 1, 1862, certain companies were shifted and merged. Company E Fourth Kansas Volunteers became Company A, Sixth Kansas Cavalry.

During the four years of active service (1861-1864), the Sixth Kansas Cavalry participated in numerous reconnaissance, skirmishes, and battles throughout Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas. The regiment engaged in disbanding small forces constantly.

According to historical records, on July 27, 1864, the Battle of Massard Prairie occurred. Confederate troops launched a surprise attack on the Sixth Kansas Cavalry encampment at Massard Prairie, less than eight miles south of Fort Smith, Arkansas. The attack occurred around 6 a.m. The Sixth Kansas Cavalry retreated from the prairie back to camp. The surprise attack proved fruitful for the Confederates, capturing around 127 prisoners, weapons and supplies.

Cotter survived this attack, only to be killed one month later in a small skirmish against rebels.

One year later, the Sixth Kansas Cavalry mustered out of service at Fort Leavenworth on Aug. 27, 1865.

Unlike the grand grave marker of Brig. Gen. Leavenworth, Cpl. Cotter received a simpler final resting place marker. Cotter’s finally resting place is located at Fort Smith National Cemetery, Section 5 Site 2336, marked on a white marble headstone.

Yet to be discovered, lost stories

As we remember those who served and died during service to our country this Memorial Day, take the time to reflect upon the numerous soldiers whose stories have been lost or not yet discovered.

Discover these stories for yourself by visiting national cemeteries, U.S. Army museums, and the National Archives and Records Administration — all great ways to learn and discover soldiers’ stories.

The Department of Veterans Affairs National Cemetery Administration maintains 155 national cemeteries in 42 states and Puerto Rico, as well as 34 soldiers’ burial lots and monument sites.

The Army Museum Enterprise consists of numerous Army museums in the United States and overseas (Germany and Korea).

To find an Army museum near you, visit https://history.army.mil/museums/directory.html.

Social Sharing