The Army is laser-focused on modernization efforts that will ensure an agile, lethal, and ready force capable of winning across multiple domains by the year 2035. However, with our eyes fixed on the future, we cannot lose sight of our readiness posture in the near-term and how it significantly impacts an organization’s ability to “fight tonight.”

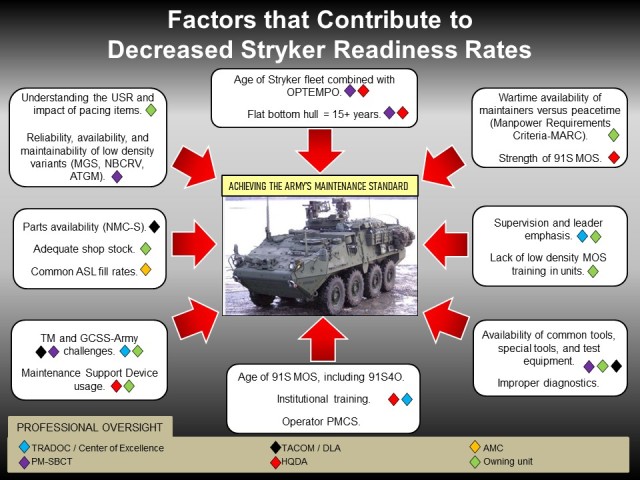

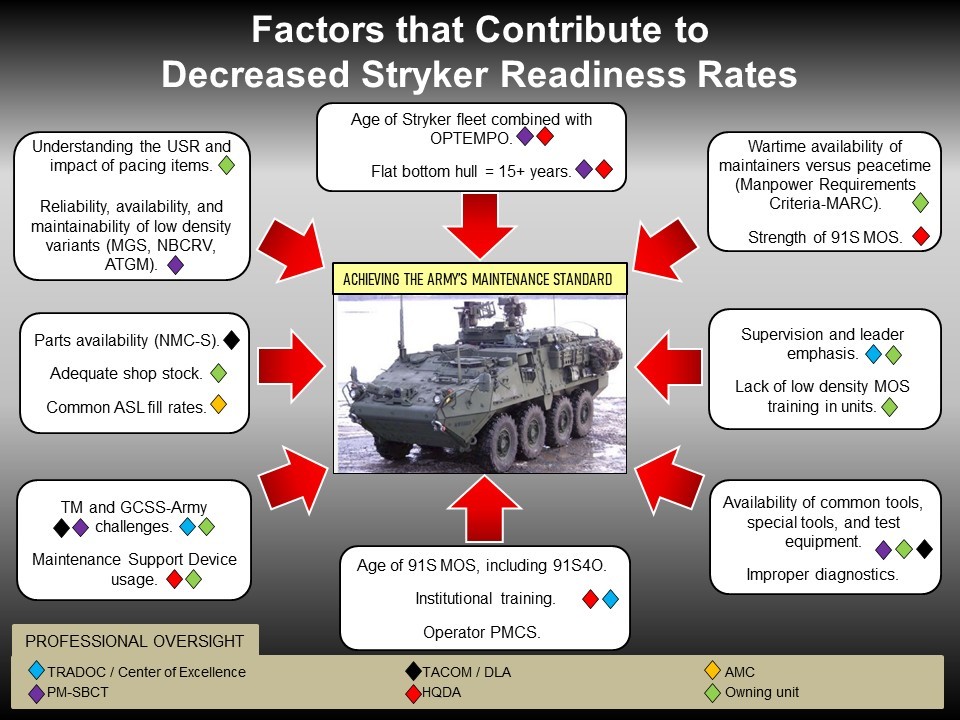

Numerous contributing factors can increase or decrease equipment readiness rates for a company, battalion, or brigade. Addressing only one or two of them will not yield optimal results. Leaders at all levels must recognize, understand and address the readiness ecosystem to have a consistent impact on building and sustaining readiness. This team of teams extends beyond the owning unit and involves numerous stakeholders including Headquarters Department of the Army, Army Materiel Command (AMC), Training and Doctrine Command, program/project managers, and Defense Logistics Agency.

While recognizing this readiness ecosystem, leaders must continuously strive to achieve and enforce the Army’s maintenance standard for all equipment. According to Army Regulation (AR) 750-1, Army Materiel Maintenance Policy, the Army has one maintenance standard, and it consists of eight criteria.

To meet the standard, an item must be 1) fully mission capable per the technical manual (TM); 2) all shortcomings (faults) must be identified using the applicable TM’s preventive maintenance checks and services (PMCS) tables; 3) if a fault cannot be repaired, there must be repair parts on valid requisition; 4) if the repair cannot be made at the appropriate level, it must be sent to the next higher level [keep in mind, this was written under the Army’s 4-level maintenance concept]; 5) all basic issue items (BII) and component of end items are present, serviceable, or on valid requisition; 6) all scheduled services are complete; 7) all modification work orders are applied; and 8) the item is compliant with all safety of use or maintenance action messages.

Unit Status Reporting and Pacing Items

Leaders need to understand the difference between equipment readiness codes (ERC): ERC-A versus ERC-P (pacing item). The Army’s equipment readiness goal for ground equipment is 90%, according to AR 700-138, Army Logistics Readiness and Sustainability. A unit’s modified table of organization and equipment (MTOE) will identify ERCs for each line item number (LIN). Due to the low density of ERC-P items in many organizations, the ERC-P readiness rate will determine the unit’s overall readiness level, or R-level. According to AR 220-1, Army Unit Status Reporting and Force Registration, the unit’s R-level is always the lowest of the two readiness rates. For example, if the aggregate equipment readiness rate for ERC-A items is 95%, but the readiness rate for an ERC-P item is 70%, the unit readiness rate is 70%. Additionally, for every pacing item in a 30-day reporting period, a unit can only accumulate three not-mission-capable (NMC) days before the item goes below 90% (27/30=90%) (26/30=87%).

Operator PMCS

PMCS is the cornerstone of the Army maintenance system. Leaders of successful maintenance programs ensure operators and crewmembers perform PMCS from the applicable -10 TM. In a recent audit of armored brigade combat team maintenance, the U.S. Army Audit Agency noted that 25 out of 47 tank crews (53%) had outdated or missing operator TMs. The operator TM is part of the BII and, as noted above, having the required BII is a criteria of the Army maintenance standard. Units must have an active publications account to order hard copy publications. It is important to note that the AMC funds publications replenishment orders so the unit is not responsible for the cost.

Some Soldiers have identified “innovative” ways to access operator TMs using their personal electronic device by placing the electronic TMs or PMCS table on a commercial file storage service and scanning a quick recognition code affixed to the vehicle’s windshield. Although effective, this is not an acceptable practice as it compromises operational security and violates the distribution statement of the front cover of the TM.

Repair Parts Availability

Shop stock (formerly known as prescribed load list) is the company or battalion’s first line of defense for stocking essential repair parts. The authorized stockage list (ASL) is another set of repair parts managed at the brigade support battalion within a brigade combat team. ASL is a predefined list of parts established by AMC, but shop stock is established by the number of times a company or battalion orders or consumes the part. Units must use Global Combat Support System (GCSS)-Army to accurately bring all of their parts to record for accountability and to establish an accurate and beneficial shop stock list.

In line with AR 710-2, Supply Policy Below the National Level, and All Army Activities Message 076-2019 on depot-level repairable items, leaders must understand and enforce the Army’s 10-day turn-in standard (30 days for USAR) for recoverable repair parts such as wheel and tire assemblies, starters, and engines. This 10- or 30-day clock starts when the recoverable item is post-goods issued in the customer’s bin, not when the unit picks up the item. Thus, it is vital to pick up parts at the supply support activity (SSA) every day. Additionally, the prompt and disciplined return of recoverable repair parts allows depots to receive, rebuild, and keep up with supply demands.

Technical Manuals

Maintainers must consistently use the applicable TM and maintenance support device (MSD) to troubleshoot, diagnose, and identify Class IX parts. The MSD is the maintainer’s diagnostic tool and stores updated TMs and other reference material. Without the current TM, the maintainer cannot accurately troubleshoot, maintain, or research repair parts, thus contributing to decreased readiness rates.

GCSS-Army Proficiency

GCSS-Army is the nucleus of readiness reporting, supply and maintenance management operations. GCSS-Army is an internet-based enterprise resource planning system that is typically updated every quarter.

Automated logistical specialists, unit supply specialists, and other users must be proficient when using the system. Supply personnel should use the new automated identification technology “My Work Place” within GCSS-Army. This functionality enhances the user interface and simplifies processes through the use of tiles and predictive text features instead of transaction codes. If on-hand, supply clerks should use hand-held tablets when picking up parts at the SSA. Scanning a materiel release order using the tablet’s built-in bar code scanner, instead of searching for the document number in GCSS-Army, substantially improves accuracy and velocity.

Within GCSS-Army, units must properly configure all systems and sub-systems in accordance with AR 700-138, Army Logistics Readiness and Sustainability. For example, the containerized kitchen (CK) is considered a system and the water trailer, prime mover, and generator are sub-systems of the CK system. The CK system cannot be employed without its sub-systems. If any of these sub-systems are NMC, the entire CK system is NMC. Proper system and sub-system configuration within GCSS-Army will provide organizations a clearer operating picture of their mission readiness.

Training

For enlisted Soldiers, training begins with Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at the U.S. Army Ordnance School that uses a skills-based training approach for maintenance and repair military occupation specialties (MOS). Considering that the wheeled vehicle mechanic is responsible for maintaining more than 350 different end items across the Army, the school cannot teach every system in the time allotted for AIT. Instead, instruction focuses on the fundamentals of brakes, engines, and suspension that can be applied to numerous systems. Soldiers graduate AIT with the basic skills needed to perform at the apprentice level. Once these maintainers arrive at their first unit, NCOs and warrant officers must provide the supervision and on-the-job training they need for progressive development.

Further, units must dedicate time on their training calendars to conduct low-density MOS training to increase proficiency. Leaders should refer to the Soldier Training Publications (STP) for each MOS. These Soldier’s manuals and trainer guides contain the current critical tasks and standardized training objectives to plan, conduct, and evaluate training. STPs are available on the Army Publishing Directorate website.

Tools

Units must have all authorized common tools, special tools, and test equipment. Accountability and kitting of special tools and test equipment are insufficient across the Army. Most fleets lack a bill of material or component listing of the special tools needed. Maintainers rely on the applicable repair parts TM to identify the special tools required for each end item. However, these tools do not have separate LINs and are not found on the property book or hand receipts. Without the required special tools or test equipment, maintainers cannot perform all of the maintenance procedures outlined in the TM.

Time

For MTOEs, the Army calculates the number of mechanic authorizations using the manpower requirements criteria formula as outlined in AR 71-32, Force Development and Documentation, and DA Pam 71-32, Force Development and Documentation Consolidated Procedures. Leaders need to understand this methodology and the difference between available time in garrison compared to wartime. Appendix C of AR 750-1 and AR 570-4, Manpower Management, outline the differences between peacetime and wartime requirements for maintainers. Furthermore, units must employ their maintainers within their MOS and not assign them to other duty positions. Some units even “protect” their maintainers and do not allow them to participate in taskings or other duties outside of their MOS. Working maintainers in their MOS contributes to sustaining proficiency and prevents skill atrophy.

Supervision

Successful maintenance programs depend on supervisors to manage processes, enforce standards, and develop expertise within their ranks. Supervisors must ensure maintenance leaders at all levels (NCO, officer, and warrant officer) receive appropriate and timely training at Army schools and institutions. Moreover, they must employ that training in duty assignments that will develop critical maintenance skills and leadership experience over time.

As outlined above, there are numerous contributing factors that affect an organization’s equipment readiness rate in the near-term. Leaders who recognize, synthesize, and address as many as possible will have the best results. Army modernization, to include prognostic and predictive maintenance, advanced manufacturing techniques, and reduced reliance on contracted logistics support, will bring exciting new capabilities as well as challenges to the maintenance arena. However, operators, maintainers, and their leaders must always recognize the contributing factors that impact readiness and the ability to “fight tonight.”

------------------

Brig. Gen. Michelle M.T. Letcher is the 42nd Chief of Ordnance and the commandant of the Ordnance School at Fort Lee, Virginia. She holds master degrees from the State University of New York at Oswego, the School of Advanced Military Studies, and Kansas State University. She completed the Senior Service College Fellowship at the University of Texas at Austin.

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Danny K. Taylor serves as the 11th Chief Warrant Officer of the Ordnance Corps at Fort Lee. He completed a Bachelor of Arts in Organizational Development and an Associate in Liberal Arts from the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, Texas. He completed courses in Capabilities Development, Manpower and Force Management, Support Operations, and Joint Logistics.

Command Sgt. Maj. Petra M. Casarez is the 14th Command Sergeant Major of the Ordnance Corps. She is a graduate of the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy class 63 and holds a bachelor’s degree in management from Wayland Baptist University and a master’s degree in organizational leadership from the University of Texas.

--------------------

This article was published in the April-June 2021 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Social Sharing