Securing the support areas in the future of large-scale combat operations (LSCO) is a central topic throughout emerging doctrinal concepts. Securing logistical nodes retains its importance from the strategic level of logistics all the way down to the buddy team occupying a listening and observation post (LP/OP) at the tactical level. Survivability is a fundamental principle across the levels of logistics and is fundamentally the commander’s responsibility. For sustainers, survivability and executing support appears to be a balancing act. However, the challenge is not balancing the two, but in integrating them both as inseparable and equally important principles. Understanding doctrinal framework for security can assist commanders in balancing mission requirements and survivability.

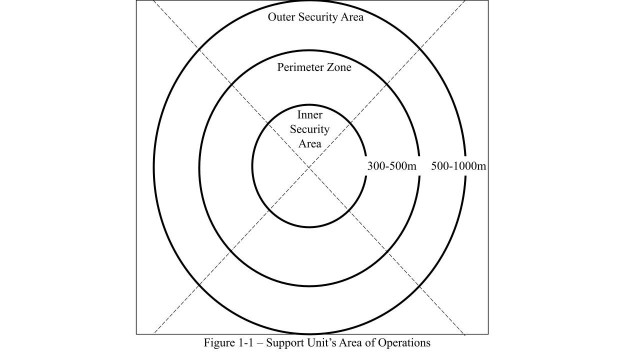

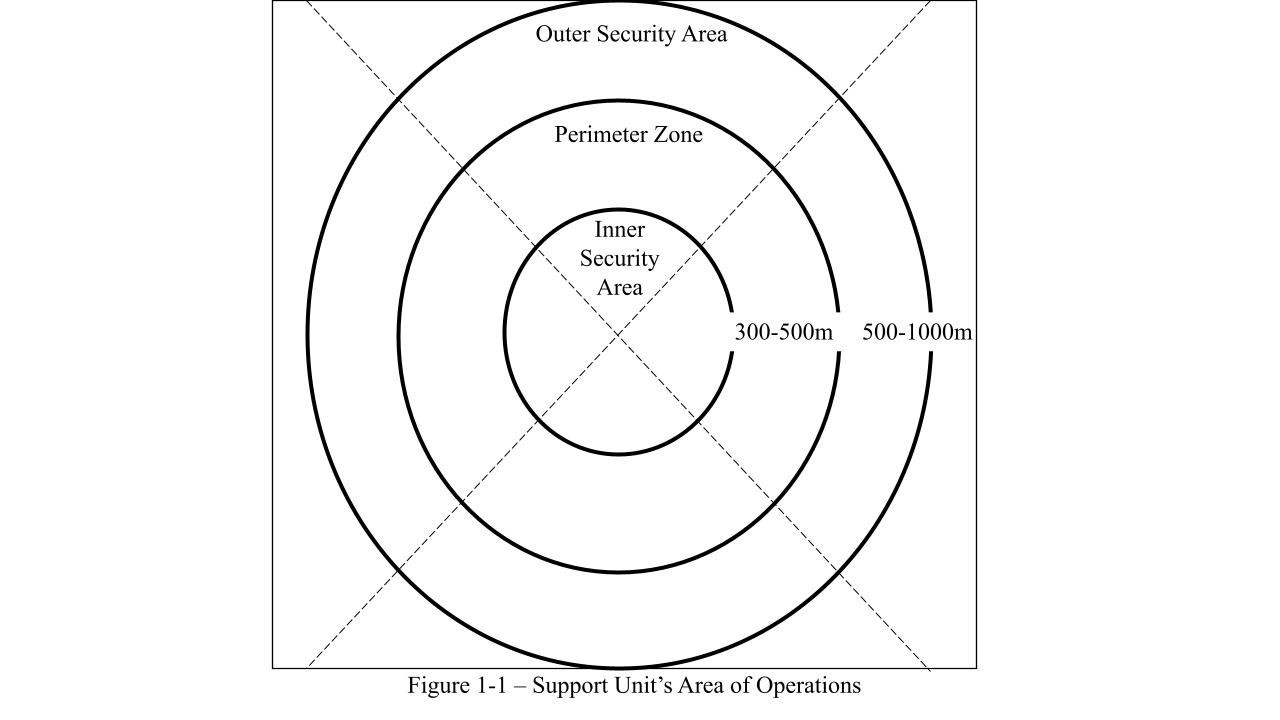

Current doctrinal framework of local security includes the doctrinal foundations of the outer security area, perimeter zone, and inner security area to provide the support commander with conceptual understanding required in developing a coherent strategy toward survivability.

Two definitions will help in understanding the material that follows. First, the support area is defined as an occupied area from which a commander projects logistical and sustainment capability. Secondly, the term “inter-functional” describes the nature of defense and security literature. It is inter-functional because the doctrinal framework for unit defense integrates tasks from protection and movement and maneuver warfighting functions. This is the basis for arguing defense of a support area is inter-functional.

Commanders must understand that the framework to visualize defense of an assigned area requires an examination of doctrine external to the sustainment warfighting function. A continued review of security and defense doctrine will support arguments made throughout this article and aid in expanding the study.

Literature Review

Army sustainment references provide useful guidance related to defense of a support area, but they also contain critical gaps. These same gaps will negatively affect a unit’s survivability if left unfilled by external doctrine or unit standard procedures. Sustainment and logistics doctrine discuss security and defense at a strategic and operational level as it relates to port opening, basing, and supporting decisive action missions in the defensive and offensive phases of an operation. There is also a timely conversation on the mobility, dispersion, and the need for frequent displacement in today’s operational environment. Furthermore, logistics doctrine covers defense responsibilities, planning considerations and guidance for developing standard operating procedures (SOP) on defense and base cluster operations. The guidance in these publications is important, but the generic nature of the content does not give commanders an effective framework to employ effective tactics and procedures. Security and survivability doctrine discuss topics on fighting position and camouflage standards, planning factors for proper cover, and enabling support, like military police (MP). However, these publications hold critical gaps for support commanders in that they focus on deliberate basing which does not support the mobility and dispersion required of expeditionary support areas. There is now draft doctrine governing support area defense, but the focus of this publication remains primarily focused at division support areas and above and still contains gaps for support area commanders at the brigade and below. This article does not hold the position that sustainment doctrine should fill these gaps. It does argue, however, that these gaps are integral to the inter-functional character of defense and security doctrine. Understanding this principle increases a support commander’s potential to develop an effective defense strategy.

Throughout sustainment literature, it is commonly understood that establishing a brigade support area able to sustain a brigade combat team’s tactical operations is challenging, requiring both defense and support options to be considered. The balance between survivability and functionality persists and is arguably one of the greatest challenges to overcome for support organizations. Sustainment literature clearly identifies the importance of security operations. Secondarily, it also includes trends highlighting that support units struggle with the employment of a security element and the defense of a perimeter. One could easily arrive at this same conclusion by examining trends published by the Combat Training Centers (CTC) as they conclude that brigade support battalions that attend CTC require additional training and increased proficiency in protection warfighting function tasks as most BSBs are not prepared to defend against enemy attacks.

Additionally, independent publications like, Rediscovering the lost art of base defense by Command Sergeant Major James A. Lafratta and Logistical Operations in Highly Lethal Environments by Captains Jerad Hoffmann and Paul Holoye (2017) reinforce this issue area as largely systemic and requiring the attention of leaders at every echelon and across all domains. Equally enlightening, however, is to understand that sustainment units struggling with the defense of an assigned area is not a new phenomenon. Maj. Anthony J. Robinson observed six training rotations in 1994 and wrote a thesis the following year on this topic where he concluded that, while at the National Training Center, sustainment units do not regularly use available resources, like doctrine, to ensure survivability on the battlefield. Current trend reporting from training centers continues to reflect similar challenges that Robinson identified over two decades ago. The compilation of past and present trends across the training centers begs the question as to why these trends continue. The size, manning, and capability of support units are relatively fixed challenges to overcome in the short term. Creative training strategies, however, provide solutions to more flexible issues like proficiency gaps in individual Soldier discipline, employment of weapon systems, and inexperience in patrolling and engagement area development. Commanders should not think in terms of dichotomies when prioritizing survivability and logistics support tasks. Instead holding the two as one in the same and developing creative training strategies that do not distinguish between them is arguably a solution that will require a paradigm shift across the force. This constant balance between functionality and survivability is just as prevalent today is it has been in recent history. However, an effective defense strategy informed by doctrine can assist support commanders in maximizing their limited capability while balancing competing demands inherent to their organizations.

Local Security Framework

The commander can visualize and frame a doctrinal security strategy. To accomplish this, commanders need to understand the doctrinal tasks of occupy and control, and be knowledgeable with the concept of local security. The doctrinal definitions of these tactical tasks bring clarity to the framework for the framework discussed below.

To occupy means that there is no enemy in that area. Additionally, the tactical task of occupation requires the commander to control the area and deny the enemy freedom of movement. Support organizations are not typically battle-space owners. However, for the purpose of defense, the unit’s area of operations (AO) is the area in which the support commander employs local security efforts.

Typically, local security is performed by a unit for itself and is a vital part of all operations. Commanders control their respective AO surrounding their occupied area. Three separate zones further divide this AO. They are the outer security area, perimeter zone, and inner security area. This doctrinal framework informs the tactics and procedures necessary for effective defense of support areas.

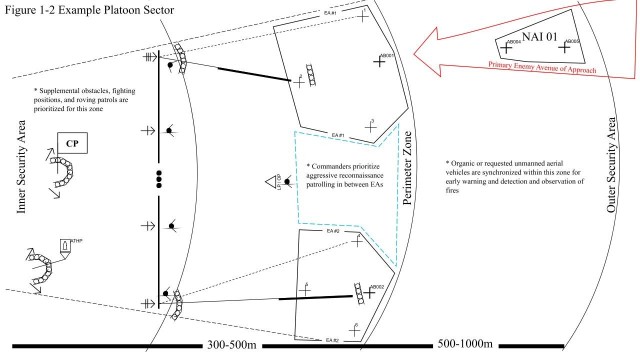

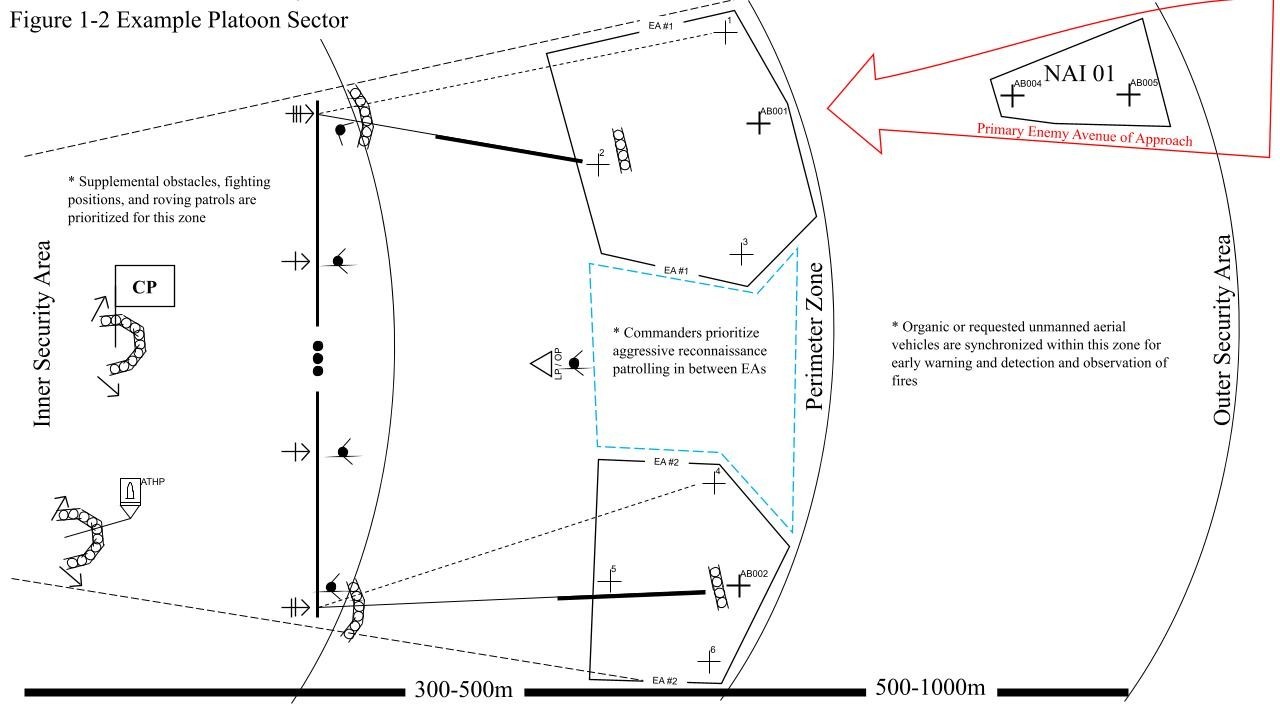

Army doctrine defines the distance of this area as dependent on the commander’s assigned AO. This gives flexibility to the commander to define that distance based on the maximum effective range of assigned weapon systems, electromagnetic, sound, or light signature, or by the micro-terrain where the enemy might occupy observation posts. With these factors in mind, a support commander could reasonably define the outer security area as extending between 500-1000 meters from the perimeter. The purpose of this security band is to provide early warning and deny enemy reconnaissance efforts. For a support unit, the amount of organic security assets required to patrol this zone is limited given the dual missions of sustainment and defense, but this should not prevent commanders from maintaining presence in this area. Unmanned surveillance or pre-coordinated reconnaissance assets not organic to the support unit are appropriate for consideration. However, given no other assets, a support commander should seek to maintain a presence using aggressive, reconnaissance patrols or other passive security measures. Additionally, supported units co-locating or receiving support might augment security efforts for a short period’s time within this zone. Support commanders should maintain a presence in the outer security area because it is this presence that will enable them to effectively occupy and control their assigned area.

The perimeter zone is the area immediately in front or behind the support area. It is reasonable to plan this area around 300 meters from the fighting positions, maximizing the effective range of small arms weapons. This is the terrain wherein the unit develops engagement areas and employs active security measures. It is essential for the support commander to preplan fires, establish direct fire control measures, and integrate hasty protective obstacles into the existing natural obstacles within the perimeter zone. This is also the area for commanders to prioritize aggressive patrolling and establish LP/OP in gaps between their interlocking sectors of fire. Because the perimeter zone is within small arms range, platoon leaders must employ effective control measures during patrols. The perimeter zone is the area wherein the enemy is most likely to exploit the defensive seams along the perimeter. Second to the active security measures that repel the enemy, an effective perimeter zone will also minimize the enemy’s ability to observe the inner area. While outside the scope of this article, engagement area development and effective patrolling are two large proficiency gaps typical of support units. However, visualizing the perimeter zone within the framework of local security can add valuable context for squads to develop creative training strategies toward unit defense. This framework also warrants a review of the support unit’s mission essential task lists to ensure they include supporting collective tasks focused on reconnaissance and security patrols.

The inner security area is the third and final zone within the local security framework. It is located behind the fighting positions and maintains appropriate stand off from the perimeter to reduce enemy observation and detection. For a support unit, this inner area fluctuates in equipment and personnel density depending on current operations. This is the area wherein commanders prioritize controlled access, security and dispersion. Congestion typically characterizes the inner security area due simultaneous execution of supported unit supply activities, logistical packages configuration, casualty evacuations, and casualty exchanges by ground and air.

Each area within this zone should employ secondary security measures to the greatest extent possible. Whether that means establishing roving patrols or constructing supplemental barriers and obstacles, commanders consider how to best secure these areas from sabotage and minimize battle damage from enemy indirect fire. An example might be supplemental security around the ammunition transfer holding point, constructing berms, establishing lanes, or enforcing access control to command and control nodes. Each defense plan of these supplemental areas should be separate, but mutually supportive of the overall defense plan. They should also identify clear sectors and proper direct fire control measures to mitigate the risk of fratricide in a perimeter breach scenario. The inner security area is the last of the three sections to an effective local security framework and is notably the most difficult to plan and control.

Conclusion

Support commanders can understand survivability as inter-functional and through the doctrinal framework of the outer security area, perimeter zone, and inner security area. This is the beginning point for developing an effective strategy toward survivability that can inform the details required in a deliberate plan. The risk of ignoring deliberate planning in the occupation, security, and defense of support areas is high and has negative consequences for the brigade commander’s operational reach and endurance. Past and present trends throughout the sustainment community validate the complexity and lack of proficiency surrounding defense of the support area. Will the negative trending continue or will support organizations begin prioritizing doctrinal tactics and procedures for more effective unit defense? Reversing this trend requires support commanders to first establish a framework for how they will defend their assigned area. This framework has potential to inform the tactical and procedural details required for more effective training strategies. As commanders transition planning efforts from conceptual frameworks of security into more actionable tactics and procedures, they will realize that maneuver doctrine identifies effective techniques for a perimeter defense, thus further attributing to the inter-functional nature of support area defense.

--------------------

Capt. Philip W. Barnes is currently assigned as an instructor to the Army Logistics University, Basic Officer Leader Department. He most recently commanded the Field Maintenance Company while assigned to the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (Airborne). Prior to command, he served as the S3 (operations officer) to the 173rd Brigade Support Battalion. While assigned to the 173rd IBCT, he participated in the planning, preparation, and execution of eight battalion and brigade combat training rotations throughout Europe where he synchronized the planning and execution of the brigade support area occupation, establishment, and defense.

--------------------

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

Social Sharing