CARLISLE BARRACKS, Pa. -- By 10th grade, Okera Anyabwile had dropped out of high school and was already no stranger to street warfare. His mother’s tears didn’t stop him from being lured into the crime-driven, fast-cash culture of 1980s South Central Los Angeles.

Growing up, he witnessed a spike in drugs and homicides in the City of Angels that led to a cycle of violence and countless shootings that claimed the lives of many of his peers.

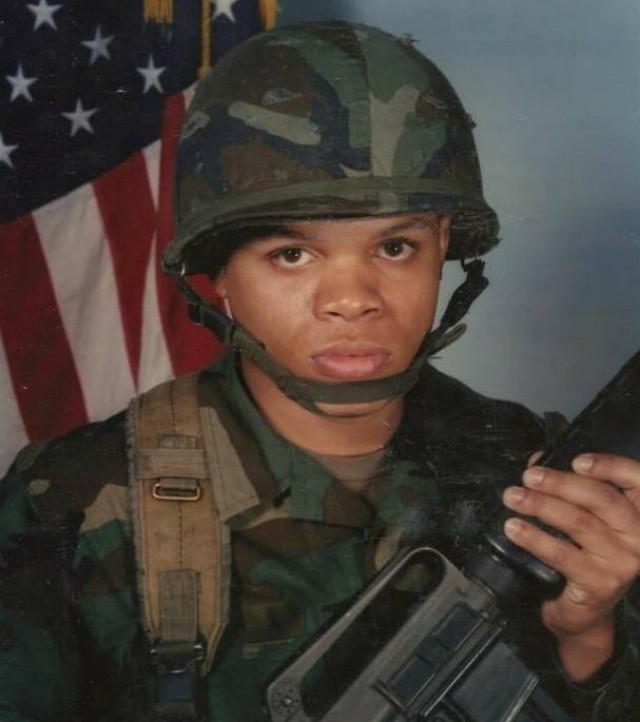

Before long, Anyabwile, now an infantry officer, found a way out of the cycle he felt trapped in through military service. His 35-year journey in the Army led him from amateur boxing, an enlisted Infantryman, to recently being promoted to colonel.

None of his success would have been possible without an optimistic Army recruiter, who never gave up on him and saved his life, Anyabwile said.

“Without him, I don’t know where I’d be today,” he said, adding he’d most likely have the same fate as many of his peers: either in prison or 6 feet underground.

Life in South Central LA

To better understand Anyabwile’s origins, one needs to go decades back to South Central LA.

At the time, violence in the area could be traced to narcotics and unemployment, cutbacks in youth programs, increased use of semiautomatic weapons, and a growing number of street gang members.

For Anyabwile, it was home. He lived in an overcrowded one-bedroom duplex in the heart of South Central, where along with his three siblings, he was raised by a single mother who “worked multiple jobs just to keep food on the table,” he said.

South Central was the pulse of a growing Black population, and often at odds with its more tourist-friendly, glamourous neighbors of Beverly Hills and Hollywood. Back then, the area was known for all the wrong reasons, he said, particularly gang violence that was fueled by a growing drug epidemic.

The neighborhood Anyabwile grew up in was ground zero for the escalating street violence, which was compounded by young men and women forced to choose between welfare and crime, he said.

At 16, he broke his mother’s heart, he said, after dropping out of school.

“She took me to the high school to talk with the principal, but I was adamant about not going back. She just cried. That really hurt, because I knew in her mind she probably saw a short future for me based on what was happening,” he said.

The misguided teenager, and the second oldest of his siblings, valued the fast cash found on the streets over his education. The reason was simple: he felt a duty to help his mom pay bills. “I ended up doing some things I’m not proud of to help my mom,” he said.

Around this time, those things caught up to his 30-something-year-old employer, so to speak, who was gunned down in the streets. His death sparked a sense of urgency in the teen.

A life-changing decision

Anyabwile, who was no stranger to being shot at, knew it was only a matter of time before death came knocking, and all of his mother’s fears would come true.

“I knew that I needed to make a change in my life and get out of the situation,” he said. “So I went to see an Army recruiter. One of my friends left for the service a few years before, and I remember him coming back and was doing alright, so I thought I’ll give this a shot.”

Anyabwile clicked with his recruiter, Sgt. 1st Class Harold Johnson, from the start. The future Soldier could see himself in the noncommissioned officer, or at least a version of himself he hoped to become. He also knew Johnson, a young African-American male, probably saw himself in the men and women of South Central, whom he brought into the Army.

“I can only assume that he wanted to help me have a better future,” he said. “With his office being in South Central, I'm certain he knew the circumstances for young African-American males during that time to the mid-80s.”

With no arrests or a criminal record, it seemed Anyabwile, who was in peak physical condition, was a shoo-in for military service. But, there was one problem: he never finished high school. This was a no-go. Without a diploma, Johnson had to initially turn the teenager away from enlisting.

However, this didn’t deter Johnson from helping him. Shortly after leaving the recruiter’s office, and feeling deflated, the recruiter called Anyabwile back and pledged to get the young man into the ranks.

To do this, he helped Anyabwile obtain his GED, enroll in night classes, and earn his high school diploma, which eventually allowed Anyabwile to enlist and hop on a bus to basic combat training.

“Maybe he saw part of himself in me,” he said, musing over why Johnson went above and beyond to get him off the streets. “It was one of the most pivotal moments in my life.”

The decision not only got him on the right track, but helped patch his mother’s broken heart. “She rejoiced that I made the decision to go back to school and into the military,” he said. “My siblings have been proud of me for making that choice to this very day.”

Although his mother died a decade ago, she was able to see her son live life to the fullest as an Army Soldier.

Came out swinging

In a lot of ways, his upbringing in South Central prepared him for life in the Army, he said. For example, he was already accustomed to excessive low-flying helicopter noise from either the LA Police Department, the Sherriff’s Department, or gunshots throughout the night. He felt at home with Army training.

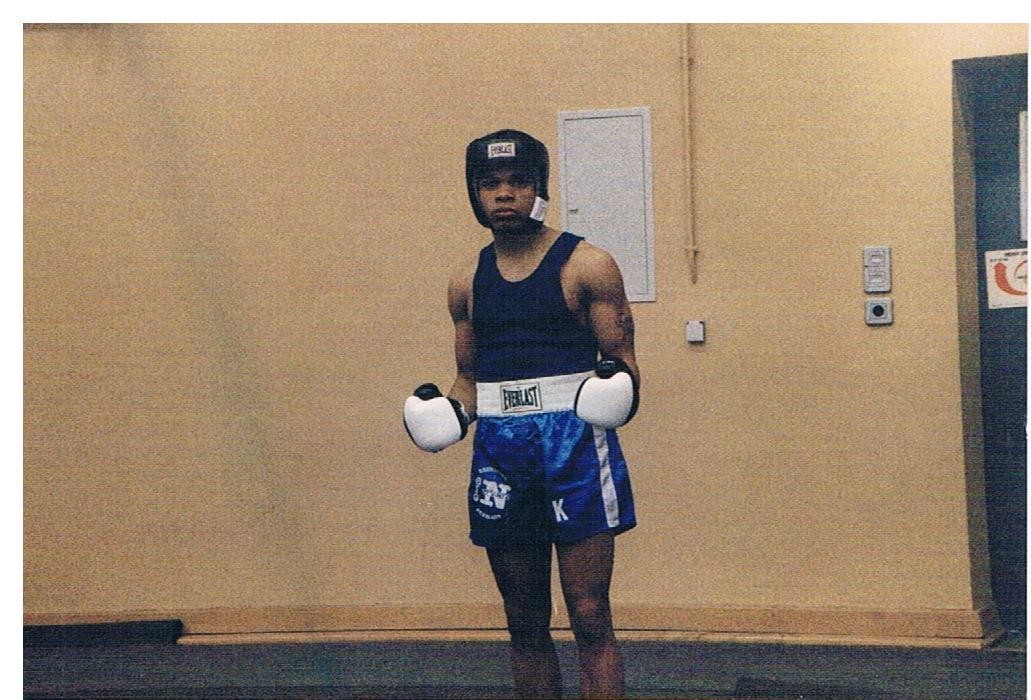

The sound of live rounds echoing all around was also nothing new for a young man raised amid gang violence. Finally, his training as an Army boxer was also an easy transition for someone who grew up in a place where fighting was an everyday part of life, he said.

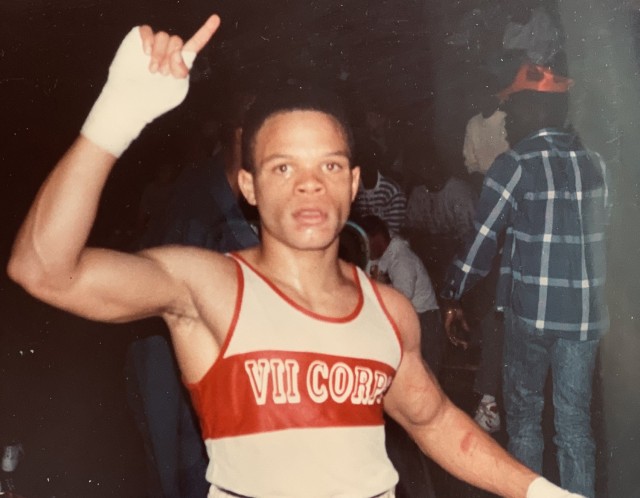

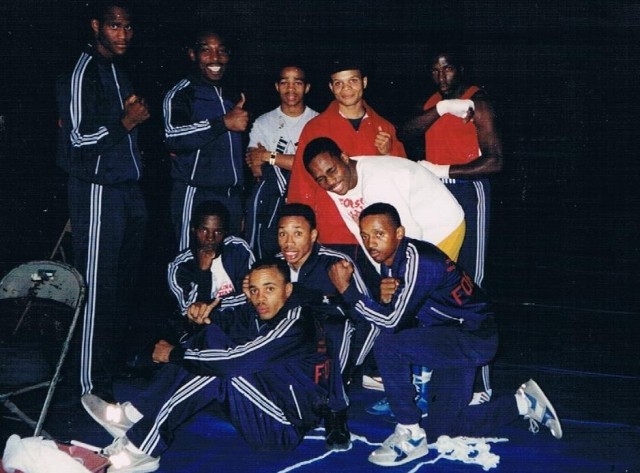

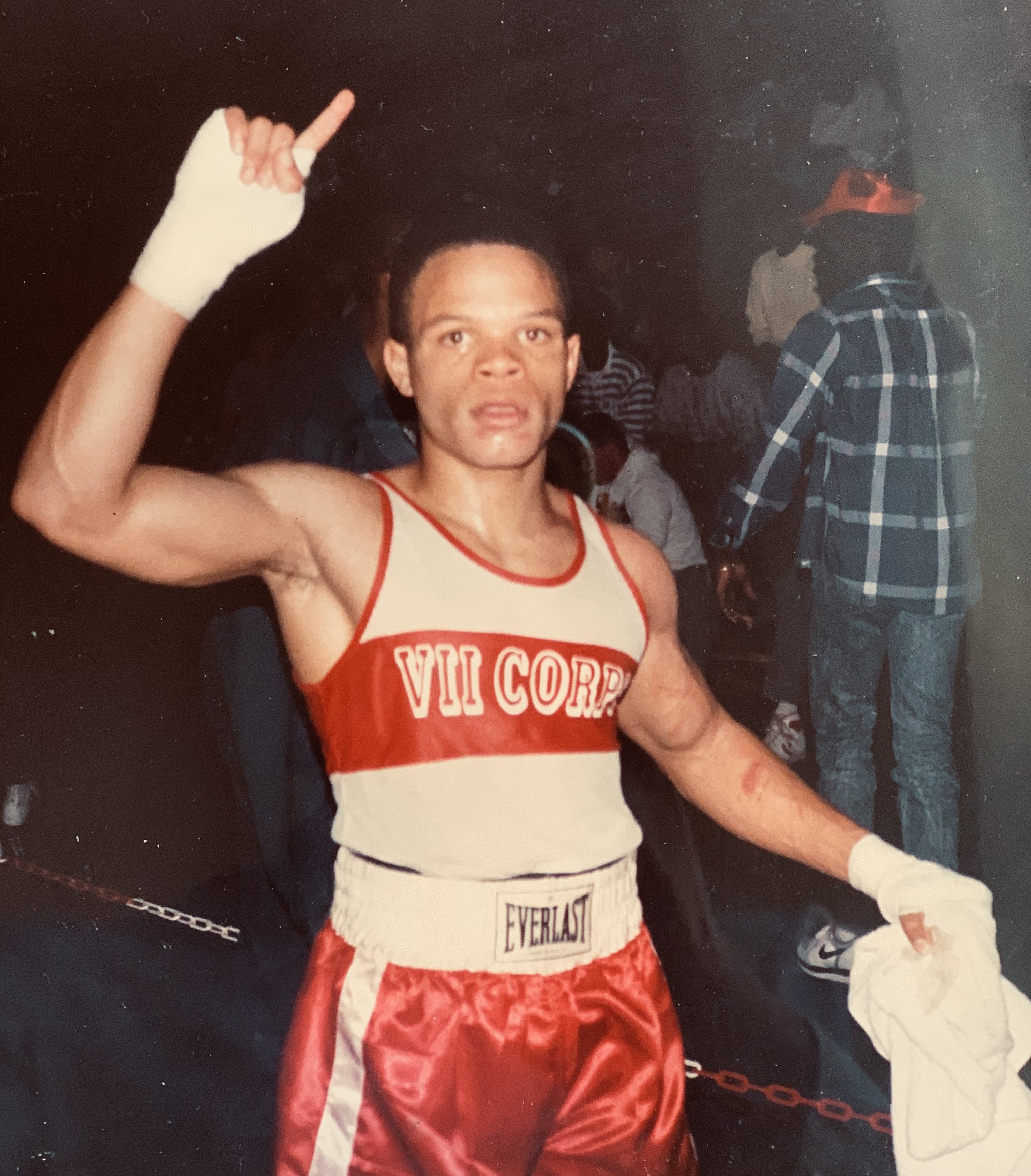

Shortly after arriving at his first duty station in Germany, Anyabwile found his calling as a boxer after winning a recreation bout with a few days of free leave on the line.

In the past, fighting was about survival and never for fun. Growing up in South Central, he never heard the roar of a crowd or felt the warm glow of spotlights. There were no referees to lift his arm in victory on the streets, or any bells to start and stop the flurry of fists.

However, the fundamentals of the sport were the same, despite how unpolished his techniques may have been. The unschooled boxer learned he was a natural, he said.

The nuts and bolts of the sport are raw. In the purest sense of the term, boxing is a sport with clear-cut winners and losers. It’s about being able to punch someone in the face, which wasn’t a new concept for Anyabwile, he said, and neither was taking a punch -- one often leading to the other.

Winning his first fight in Germany did more than earn him a four-day leave pass, though. It also opened the door to travel the world fighting for the Army. Over his three-year stint as an Army boxer, Anyabwile collected a series of championships and accolades.

“[Fighting was] just the nature of where I lived,” he said. “We had to learn to fight, and it wasn’t through the police athletic league.”

While on the Army’s boxing team, the fighter trained in a way he never had done on the streets of LA. For example, the mechanics of a punch -- how to tighten his fist with each blow or when to fire off a spree of punches at the right moment -- taught him how the sport was technical.

Anyabwile then came to another crossroads in life.

“I had to come to a decision. Either I was going to get out and try to become a pro or I was going to stay in the military,” he said. “I was a pretty decent boxer, but I chose to stay on as a Soldier.”

From boxer to full-bird colonel

After hanging up his gloves, Anyabwile “committed to Soldiering as an Infantryman,” he said and focused on his next fight -- to become an Infantry officer. “I wanted to be more than an NCO. I wanted a seat at the table to make decisions to help Soldiers.”

As an NCO, then-Staff Sgt. Anyabwile “felt a deep sense of helping Soldiers,” he said. But driven with the task of helping others, he hoped to “shape the lives of more Soldiers” on a larger scale within the officer corps.

Because of his early South Central roots, he had to overcome his own personal misbeliefs. “I always thought that [becoming] an officer was this high bar, and because of the stock that I came from, there's no way that I could get selected,” he said.

That personal bout ended in 1999 after he was selected for officer candidate school. A born fighter, it came naturally for the freshly-pinned second lieutenant to join the infantry, he said.

Since then he’s moved through the ranks to where he is today, serving as director of the Strategic Simulations Division at the U.S. Army War College.

Along the way, Anyabwile has held onto an appreciation for his mentors. From the recruiter he met as a troubled teenager to Army leaders at the highest ranks.

“I have known Okera for 20 years. He is a focused, dedicated and caring leader with an amazing life story, and I was honored to promote him to the rank of colonel,” said Lt. Gen. Gary Brito, Army deputy chief of staff, G-1. “Obstacles can be breached and dreams can be achieved.

“Okera’s journey highlights the amazing opportunities that our Army can offer to citizens with the drive, desire and passion to serve,” he added.

Anyabwile credits Brito for being his longest-serving mentor. “When I commissioned and showed up at my first duty station [as an officer], he was a battalion operations commander,” he said. “He was a great mentor, great coach, and it set the tone for me moving forward.”

In the past 35 years, South Central moved on without him and many of his peers, Anyabwile said.

“Life in the inner city goes on,” he said. “It’s like when someone goes off to prison or gets killed, there’s not a lot of memories of that person anymore. You’d think if a member of an organization -- or as they call gangs -- goes off to prison, that because of the tightness of the organization, [members] would visit them. But no, people are forgotten.”

However, it seems Anyabwile has not forgotten his peers, the opportunities he was given by the Army, or the neighborhood he came from.

“I look back and ask, what if someone [like Johnson] would have shown the same type of concern or given the same opportunities to many of my peers who were in the same boat as me?” he said. “I don’t see myself as some unicorn. I was just given an opportunity” by an optimistic Army recruiter.

“If my peers in the inner city of Los Angeles had the same opportunities as me, I think many of them would have been just as successful, if not more [successful] than myself,” he said.

Part of Anyabwile feels his continued service helps pay forward a debt owed to a recruiter who believed in him and maybe saved his life. From being a high school dropout to finishing his third master’s degree, the colonel who “just wanted a seat at the table” to help Soldiers is how he has paid that debt, he said.

“I really do believe that if more people, whether in the inner city or rural, are given an opportunity, they will succeed,” he said. “I'm a living testimony to that.”

Related links:

Social Sharing